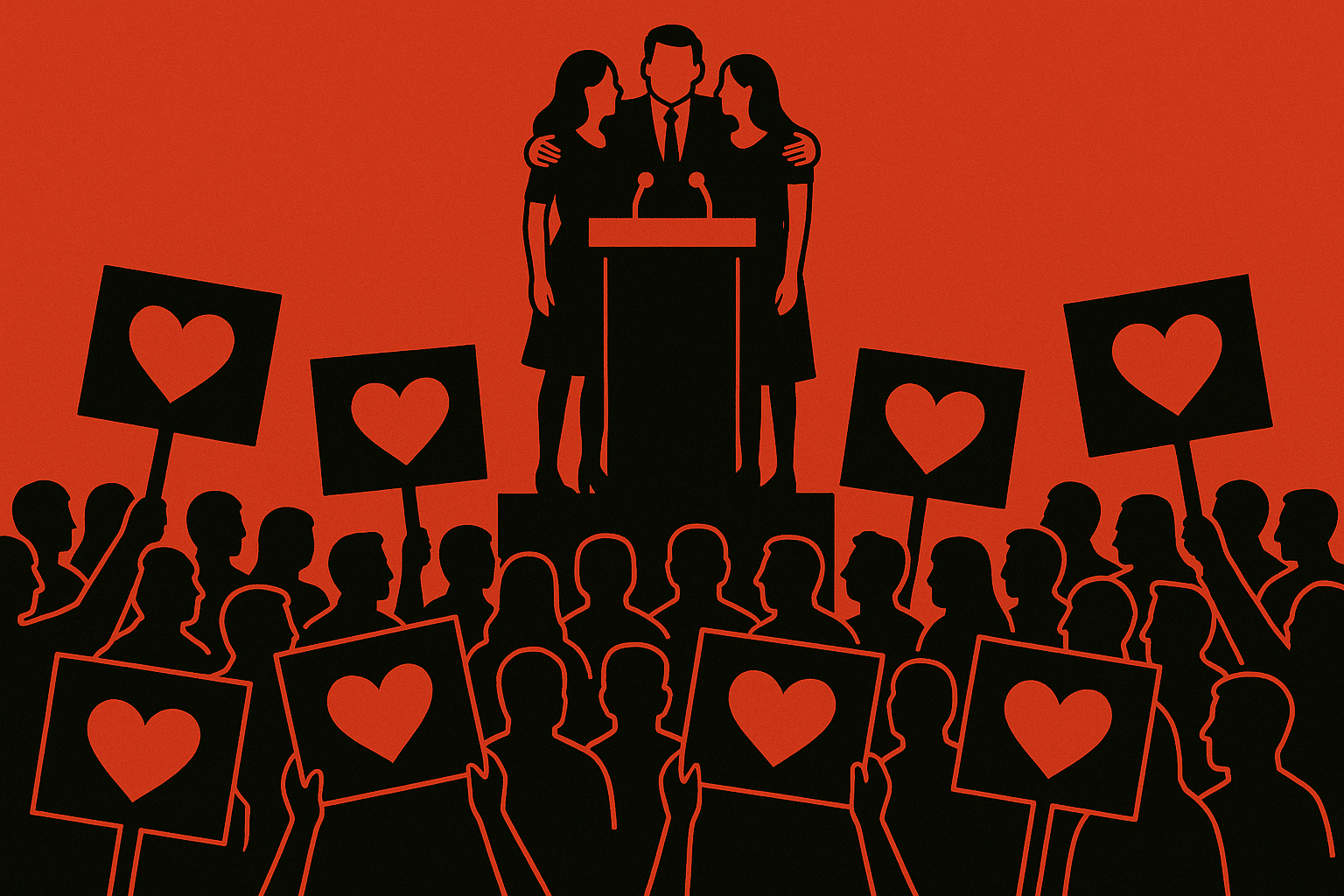

The Good Father Syndrome: Why Strongmen Still Seduce?

In this episode of International Horizons, RBI director John Torpey speaks with Stephen Hanson and Jeffrey Kopstein, co-authors of The Assault on the State: How the Global Attack on Modern Government Endangers Our Future (Polity Press, 2024). In this conversation, they discuss how today’s right-wing movements, from the United States to Hungary, are waging a new form of politics that undermines the very foundations of the modern, rules-based state. Drawing on Max Weber’s concept of “patrimonialism,” Hanson and Kopstein explore how these leaders erode public trust, demolish impersonal bureaucracies, and replace rational governance with personal loyalty and whim. Along the way, they examine the role of conspiracy theories, the rise of “deep state” narratives, and the uneasy alliances connecting libertarians, Christian nationalists, and advocates of an all-powerful executive.

Transcript

John Torpey

Right wing movements and thinkers around the world are at odds with the state these days. This is a shift from historical conservative movements, which, at least in Europe, were eager to strengthen the state as part of their competition with other states in their neighborhood. The United States has long been an outlier in this regard, as anti statism tends to rub deep in the veins of American conservatives. Now there’s an attack on the state as such, it seems, which threatens to make the state the possession of personalistic rulers who rule by whim. Does that sound familiar? So what’s going on? Welcome to International Horizons of podcasts of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and we’re fortunate to have with us today, Stephen Hanson and Jeffrey Kopstein, authors of the new book The Assault on the State: How the Global Attack on Modern Government Endangers our Future, which was recently published by Polity Press. Stephen Hanson is the Letty Pate Evans professor of Government at the College of William and Mary, and Jeffrey Kopstein Is the Dean’s Professor of Political Science at the University of California at Irvine, where I once taught, although before he got there. But the full disclosure is that he and I played basketball and street hockey together in graduate school, once winning the UC Berkeley intramural street hockey championship. So we are blood brothers. Thanks for being with us today, Steve Hansen and Jeff kopstein.

Stephen Hanson

It’s a real pleasure. Thanks for inviting us.

Jeffrey Kopstein

Yes. Thank you very much.

John Torpey

So thnks for writing the book. So you argue in the book that the dichotomy between democratic and authoritarian states, so much discussed in recent months and years, focuses only on how leaders come to power or are chosen, and hence misses a form of rule that has long, a long history, and that backs Weber called patrimonial. Can you explain what that means and why it has become so important in contemporary world politics?

Jeffrey Kopstein

Yeah, so this is Jeff, and I will, uh… As you say, quite correctly, this big divide between authoritarianism on the one hand and democracy in the other, this is a kind of a core category that’s used by almost all analyzes of politics. So when you look at, let’s say, the Trump phenomenon, or the Orban phenomenon, people say this is the rise of right wing populist authoritarianism. And as you say, this really concentrates on the question of how leaders come to power. Are they elected? Do they take over? Right? And that, of course, makes them democratic. If not, then they’re authoritarian. What Max Weber tells us, right-the great German sociologist-is that no matter how leaders come to power, the core relationship of any leader is obedience to the rule by his or her, but mostly his, in this case, staff, right? And if a leader comes to power and, let’s say, pulls the lever by issuing an order and nobody listens, then it doesn’t really matter how the leader came to power. And so what Weber tells us, what’s really to concentrate on is how rule is carried out, not how you come to power. And historically speaking, for the vast majority of human history, orders were followed based on highly personalistic relationships of affection, of loyalty, of fealty. And Weber called that, that personalistic relationship, patrimonialism. The order that we live in now, or at least until very recently, the order that we live in now, is really one of what Weber called legal rationality, that is, you obey, not based on personal relationship, but based on a legal relationship, based on the order coming from the office, not the person coming from the President, not Trump. And that’s what’s really important for Weber.

John Torpey

Steve, did you want to add anything to that?

Stephen Hanson

Yeah, maybe just a couple of things. I mean, one is, we think that by analyzing the state and its relationships of elite and staff, you can switch out of a problem we often have in analyzing people like Trump, which is that they win elections, right? So if we call them undemocratic, there’s immediately the problem that they won fair and square according to the rules of the game. And on the democratic party side, you see people sort of tying themselves in knots trying to figure out how to handle that. You can’t really oppose him as an authoritarian populist when he was freely elected, but you certainly could oppose him if you want a rational, legal state, as Jeff was saying, if you want a state that’s based on law, impersonal procedures, meritocracy, you know, and recruitment according to merit, you know, as opposed to loyalty or fealty. And so both are important, you know. It’s not that we don’t want democracy. We do, and over time, a patrimonial style state will tend to erode democracy’s quality anyway. But in the short run, the issue we’re facing now isn’t so much democracy per se, as it is the destruction of the rational, legal state that we’ve lived in for the last several decades.

John Torpey

So and in the book, you focus a lot on the rise of, well, you call it the bogeyman of the deep state. And you know, you discuss its history really emerging in late 20th century Turkey, which I also experienced having taught myself in Turkey about 25 years ago, and it was the first time I really encountered the term and the idea. But of course, it means something different, really, in Turkey than it does here. But could you talk about how this notion of the Deep State has become so widespread and so widely believed as a kind of folk theory of what’s going on out there?

Stephen Hanson

Sure, and, you know, we trace this in the book carefully, because it turns out that about half of Americans, in public opinion polls do believe there’s such a thing as a capital D, capital S, Deep State-some hidden force behind the scenes that’s, you know, pulling the strings we don’t understand. So it’s a really important phenomenon in American politics and beyond America. Now this kind of terminology is used in Israel by Netanyahu, even Boris Johnson used it at one point when his power was threatened, started talking about the “Brussels Deep State,” quote, unquote. So as you know, the term originates in the in the 1990s in Turkey, this is the result of a kind of unexpected car crash in which an luxury automobile is hit by a truck, and the police come to the scene, and who’s in the luxury automobile, but high ranking police officer in Istanbul, a member of Parliament from the pro regime party, and the notorious gangster totally, you know, who had been wanted by Interpol along with his girlfriend, who was also there, they got killed in the crash, and when they opened up the trunk, they found guns and fake identity documents, and there was no way to disguise the obvious truth here, which was that the underworld was conspiring with pro regime politicians and the police to do dirty tricks behind the scenes, to attack the PKK, the Kurdish party, or to attack people who didn’t like the regime. So it made sense in that context to say that there was a Turkish deep state, a state that was hidden, that was behind the scenes, that was doing dirty tricks, and that spread from Turkish analysis to much of the Middle East. So people started looking at the Egyptian deep state or the Iranian deep state. All of this made a certain amount of sense. It morphed then when it came to the United States, and a certain strand of actually left wing opinion started talking about how the military industrial complex in the United States could also be analyzed as a deep state. So, you know, spying too much on Americans, gathering the information for purposes not always revealed. And some of that analysis was also quite sensible, and some of it kind of started veering into some conspiracy theory oriented people who really were no longer interested in discerning the causes and the actual people, but just talking about a kind of big, amorphous entity out there that should be taken down. So it’s interesting that the origin of the term is actually on the left politically and not on the right, but it ends up turning into a right wing phrase, because there’s a kind of commonality here. We talk about where the right, especially under MAGA now and similar movements around the world, see the state itself, the administrative state, as they like to call it, as a kind of conspiracy unto itself. What Weber called Rational legal order, strikes them as conspiratorial, as somehow blocking liberty, as blocking the expression of faith. And for all of these reasons, you end up having the term Deep State taken over from the left by the right. And now, actually, there’s still elements of the left in the United States that kind of agree with this notion that there’s a hidden force that needs to be taken down.

Jeffrey Kopstein

Yeah, just very briefly, there’s… We did try to get to the bottom one of the things we couldn’t achieve in the book, right? Lots of things, but one of the things we couldn’t achieve, and we tried to get to the bottom of how that term actually migrated the carrier, how it migrated from the left to the right, how it went from somebody like professors at Berkeley talking about the deep state to Steve Bannon talking about the deep state. And we rarely, never found the smoking gun. I mean, one of my suspicions was always that it was Glenn Greenwald, right? And so I read a lot of what Glenn Greenwald said and wrote, and I never found it right. So somebody more clever than us could, or more dogged, perhaps, could get to the bottom of how that went. But as Steve said in the end, right, in the popular, populist mind, right, the distinction between Deep State and administrative state, which is, of course, a much more of a kind of a legal category that’s popular, you know, at law schools, the distinction between those two things has sort of been lost, right? It’s all now really meant to denote unaccountable bureaucracy.

John Torpey

Well, it somehow has to do with the rise of conspiracy theory. Theories and the demise of trust in government, which you guys, you know, document in the book. I mean, I was always struck by the way in which it was a kind of the deep state, was a defender of the Kemalist state in Turkey, and it, you know, rose up when there were, you know, Marxist or left wing coups attempted, or there were Islamist coups, which they also, you know, opposed. So it had a very peculiar Turkish inflection. But what’s interesting is, what you show is that it’s now basically across the board. People just don’t like the state, and they think it’s a deep state or an administrative state, that those are somehow, you know, evil forces, shadowy forces.

Jeffrey Kopstein

It does go to how we actually came to write the book. It was during COVID and there were, you’ll remember, there were, of course, all these proposals for public health provisions, and it wasn’t so much that whether you agreed with one or agreed with the other, nobody could agree on anything, and what they couldn’t agree on anything, because the public trust for any institutions had so eroded. I just wanted to throw that in as a kind of to really that issue of trust really motivated the entire book.

John Torpey

Yes, well, it’s obviously hugely important as far as what’s going on. So you describe in the book, somewhat in the United States anyway, a somewhat sort of oddball coalition, libertarians, Christian white nationalists, as Phil Gorski and Sam Perry dub it, and Federalist Society originalists who do not obviously share a great deal in common politically. But so maybe you could tell us about how this coalition came together.

Stephen Hanson

I’ll start off and throw it over to Jeff, because one of the things that’s interesting is some version of that coalition exists in many of the cases of patrimonial rule around the world that we talk about. So the US case, though, is particularly significant for obvious reasons, and we have the strongest libertarian movement of the world. And so you know, the first group that hates the state descends from Ayn Rand, and you know, people on the on the libertarian economic front who basically see the state as an obstacle to liberty, because they’re, you know, had this experience of the Soviet Union, Hayek and others you know, who saw planning as a path to tyranny. And therefore we’re very, very scared of the sort of encroachment on the public arena of a growing administrative state. It has gotten bigger over the course of the 20th century. And if you saw that as kind of proto communism, naturally, you’d oppose it. But that’s taken an extreme form, and in particular in Silicon Valley, you know, so the Peter Thiels of the world and others who are looking at, you know, options for living in space or options for living on the ocean, so that you can never have any state ever control you, you know, this has actually become an important part of that coalition. You see it with Elon Musk, for sure. And then the second part is the Christian nationalist part. And here, the opposition to the state is really because it’s too secular. You know, it comes out of the notion that the state stops us from expressing Christianity in the public sphere, “we can’t say Merry Christmas anymore,” you know, all these kinds of tropes are used different for libertarians, right? Because a lot of these folks want a theocracy, and they’re quite explicit about it. So the Libertarians are mostly atheistic or agnostic. And you see that actually right now, between Bannon and Musk, you know, this sort of two coalitions really hating each other. And finally, the Federalist Society part is really interesting. It overlaps to some extent, with the Christian group and particularly with people like Leonard Leo, which is conservative Catholic orientation. But really what got them started was Nixon and what they saw as the over constraining of the executive after Watergate by Congress, leading to people like Robert Bork being rejected for the Supreme Court, and their argument about the so called unitary executive theory was designed explicitly to try to reproduce a powerful executive of the sort they saw being forwarded, especially when Republican presidents came to power, and you see that on our Supreme Court today. So our argument is that those three sources in one form or another are all over the world. There are libertarian movements everywhere. In the UK, you saw that with Liz Truss, for example. You’ve got religious traditionalism in Putin’s coalition as a very important factor. And then you’ve got just people who like the executive and want to strengthen it. And that has appeal, as we see, even for some non White voters. So we should point out, while there is a kind of White hierarchy and some of the Christian nationalist stuff. And it’s quite explicit, the coalition is actually broader than that.

Jeffrey Kopstein

Yeah. So Steve alluded to it’s the presence of this sort of this holy alliance, or unholy alliance, not only in the United States, but in Hungary in Israel. In Israel, exactly, Netanyahu himself started off as sort of a libertarian. And then has this allies religious nationalists, right? In this case, not Christian, but Jewish nationalist. And then, of course, most recently, the rise of kind of unitary executive theory, without, without the actual words unitary executive theory, the attempt to disempower both the bureaucracy the police. But, and of course, most recently, the judiciary. You have that in Great Britain instead of Christian nationalism per se, although that exists in Great Britain, you also get the kind of move to traditionalism along with libertarianism, right? So you have, and it varies from case to case, but, but in each case, all three of these strands find something in the patrimonial leader that they like, even though, if they actually ever came to power, you think about it, right? If you’re an advocate of unitary executive theory, well, if you were a Christian nationalist, you wouldn’t necessarily like it if Bernie Sanders became president, right? Because he’d have a lot of power. He could pull all kinds of levers that you might not like. So what they see in these traditionalist the good father, patrimonial leaders, is someone who might give each of them something of what they want. And Trump’s been pretty darn good at doing that.

John Torpey

And he’s the guy, right? So, you know, I want to get back a little bit to this, the importance of this notion of patrimonialism, which may be kind of alien to, you know, non Weber nuts like us. And you know, you stress basically that what the stakes are is about a shift from the rule of law, you know, bureaucratic legal rationality, as Weber would call it, to the rule of men, to a personalistic form of rule. And why is that happening so broadly? And you know, what can be done about it? I mean, you emphasize, you know, renewing a sense of the value of public service. But I I worry it may be too late for that.

Jeffrey Kopstein

I mean, I think what you have to do is look at why we’re getting it into be to begin with, right? And, you know, there’s actually an awful lot of research on out there on why we’re getting these kind of populist rulers, and it really boils down to kind of two factors. One is kind of international markets and globalization, which is sort of hollowed out the middle class, right? And that’s a well known, a well a well known hypothesis, and there’s certainly an element of truth to it. And the second, the second case is increasing heterogeneity of our societies produced by immigration and the inclusion of people who were previously excluded. And those two factors have created a kind of a demand among people who feel themselves to be the losers of modern capitalism, the losers of modern neoliberalism who want to have these problems addressed in some way, what most people don’t look at is, well, so that’s, let’s say, the demand side for these strongman rulers. What most people don’t look at is the supply side, right? That is what is actually being offered out there, and the idea that of going back to a previous mode of rule, where daddy ran things, where there was a good father who ran things, who took care of us, who knew us, who would take us back to a world that we thought maybe in our minds had existed before. Of course, it never actually existed in that way. But who would take us back to a new world, who wouldn’t be constrained by the rules, who wouldn’t be constrained by the laws, who could then, therefore, just solve the problems. You have a problem with crime in the streets, you just pick everybody up and send them to El Salvador, right? It’s not a problem. And so there’s a certain appeal to all of that, and we need to understand where it actually came from, right? So most people have looked at the demand side for this, and that’s true, we agree, but very few people have actually looked at well, so what’s on offer? What’s our menu? What do we actually get to look what do we get to choose from? And it turns out, then, case after case, it appears to be the same kind of thing. And interestingly, it did not start in the United States. It spread to the United States. And I think that’s where really Steve has a lot to say on this.

Stephen Hanson

Yeah, if I can add just a couple points to just overview. I mean, one is that all of this was so unexpected because our minds were trapped by an older form of modernization theory. You know, people just assumed, once you got a modern state with modern, you know, legal institutions and modern bureaucracies, it was irreversible. The idea you could go back to 19th century style politics on every issue you can imagine was just not in, you know, anyone’s mindset. So that kind of, you know, one dimensional notion of history really blocked us from having that imagine, imagination really to see what would happen. The other thing that people tended to do is ignore the countries that were not immediately the most powerful in the world, and Russia being the key example. So now you’ll hear this coming from a Russia specialist who lived through the 2000s when you know the average person said Russia is finished as a famous headline once blared, and you know when you said you actually might need to pay attention to that place, because they’re rebuilding the state quite powerfully, and they’re rebuilding their military, and you know, it’s still a really large country with a lot of nuclear weapons. All of that fell on pretty deaf ears in the 2000s and even into the 2010s, but what was going on in Putin’s rush after 2000 was a step by step process of building. A patrimonial empire of the sort that the czars had back in the, you know, until the early 20th century and others who were looking at that question of how to create the supply, as Jeff said, how to build something other than the neoliberal order. We’re looking at Putin and increasingly admiring him. So this strange phenomenon where, on the right, you know, for example, in Christian groups in the United States, you find people who say, well, actually, that Putin is a good guy. I mean, he’s a Christian. He’s a believer. He doesn’t like alternative sexual activities. He built a strong state. He likes hierarchy. And that appeal was missed by people who also sort of ignored the uprising of a new world order on the periphery of the liberal system, and in Russia, we think, is where it started.

John Torpey

Very interesting, because I probably don’t follow Russia, Russia developments as closely as you do, although you know, his opposition to what we think of as a modern regime of rights and human rights is obviously, you know, not his thing. So we’re getting towards the end here, and I really want to ask a major question for me, which is, how does the book suggest we get out of the mess we’re in today? The book argues that the crucial first step is to get the diagnosis right. And I agree that that’s important. But there also seems to be a lot of impatience with temporizing and a felt need for action. I just saw that, you know, there are supposedly more than 1000 demonstrations scheduled for tomorrow nationwide. You know, the question to me is, will they make a difference?

Jeffrey Kopstein

Well, I mean, one of the big differences with-although it may have started in Russia-one of the big differences with the in the case of the United States or in the developed West, these patrimonial rulers who come to power, not only do they have to build up a new kind of state, but in the first instance, what they have to do is demolish the existing state, right? And that’s the phase we’re in right now, clearly, right? All of us have friends who’ve worked in the government in various places, who just you know, have been received the “Dear Colleague” letter or some other form where they’ve been just brought in and dismissed. So we’re dealing right now with the deconstruction phase. The second phase will then be repopulating it with loyalists of Don Corleone, right, who will kiss the rain. And so we’re dealing now with the demolition phase. So I think it’s hard to demolish a state that the American state, has been built up in a slow process of accrual, right, over many decades. And so right now, the resistance is really, will we actually want to have our food safety diminished? Will we actually want to have our air be dirty? Will we actually want to have our old people not receive their social security checks? Will we want to have are museums destroyed, right? That they’re all somehow DEI for this group or that group or whatever. And so what we’re seeing now, I think the what should be the focus is not only on democracy writ large, but actually on saving our state institutions, right? And so that goes to your question, John, which is a very important question these demonstrations, what are they actually doing? What are they demonstrating about? What are they calling for? I think focusing on the real things that people need. We like our modern state. We want our modern state, our modern state should be valorized, not denigrated and wrecked, right? And so, you know, I think what those demonstrators should be out there doing, and I might be part of it right, is to have very concrete demands. Right to focus things on people who, otherwise, perhaps maybe even even have voted for Trump, or may have said, You know what? The state is too large. The state is inefficient. We don’t want the whole world to be run like, you know, Newman on Seinfeld, right? That the US Post Office on Seinfeld, right? The caricature of the US Post Office, right? And so I think that’s the core, is a re appreciation of the modern state, and then getting out there and telling the government “Hell no, you can’t do that to our states, and you can’t do that to our universities,” because it’s not simply the state itself, it’s also the expertise, the education that’s required to produce the modern society that we live in. Do we really want to get rid of all of that? So if there’s to be a resistance, and I think there should be, that’s what it should really be focused on in the first instance.

John Torpey

I totally agree. And you left out the spread of another pandemic. But let me turn it, turn it back to Steve.

Stephen Hanson

I’m going to add-I really just endorse everything Jeff said-but I’m going to add a foreign policy dimension, and that’s the war in Ukraine. And we do talk about it in the book. So one way to understand that invasion is Putin’s frustration at not being able to install a loyalist as the president of Ukraine. He has that in Belarus with Lukashenko. That’s the way he understands world order. It’s actually the way Trump understands world order. Part of our problem here is with Orban, and Erdogan, and Netanyahu, and Trump, and Putin. We have so many of these people in powerful positions, even Xi Jinping has been moving toward a patrimonial interpretation of Leninism in China recently, as the big father of China. So you know, you really have a danger. You have the five or six families in the mafia image. You see the world as kind of made of strong families. And then play things where you divide up the turf with occasional turf wars on the edges. And if you see the Ukraine invasion, the full scale invasion as being motivated by that then resisting it becomes not just a matter of defending democracy in Ukraine or defending the sovereignty of Ukraine, both of which are incredibly worthy causes, by the way, but it’s also a geopolitical dimension of defending the modern state Ukraine, in alliance with the Europeans, is another bastion of prevention of a kind of clientelistic rule strategy, which Ukrainians know and hate, and they to a person understand that being reincorporated into Putin’s zone of influence would mean returning to this arbitrariness, this corruption, this personalism, as well as subordination to an enemy nation. Now I think there’s some hope here, and I’ll be really quick. It’s odd, but Trump kind of didn’t realize how complicated it was. And people like Witkoff, his friend, who has been trying to do in the negotiations, they still sing Trump’s phases praises, and they give him kind of, you know, concession after concession. But so far, knock on wood, they haven’t been willing just to say: fine, you get everything you want, and we retreat and do nothing. And the reason for that is, just as Jeff was saying, there’s a lot of people in the United States who do care about state services. There are a lot of people in US, Congress and the military, who do care about not losing face entirely with our investment in defending the sovereignty of Ukraine. So I think the foreign policy dimension here is important and should also be be recognized.

Jeffrey Kopstein

You mentioned hockey at the very beginning, right? As you know, I’m born in Canada, right? And Canadians are taking this all very seriously, just as Putin wants to have Ukraine, Trump wants to have Canada, Greenland or Panama or God knows, who, where, where else. And it’s the same logic. They don’t view borders as legal. They viewed them as historical or part of potential patrimony, if you’re interested in patrimonialism, the whole notion of patrimony brings up a territorial element for all of this. And so it’s, it’s all opposing. This is sort of all of a piece. We don’t want to go back to a world either of a domestic world in which we don’t have legal, rational state, nor to a global world in which states don’t relate to each other along legal lines, a rule. When we talk about the rules based order, that’s what we mean. And the alternative to that, the alternative that is not some return to kind of some notion of realism, but the alternative to that is the return, to return to a world in which we’re all trying to conquer each other and take over each other’s territory all the time, right?

John Torpey

And the whole society, in a way, is organized around the same kind of principle. Those who have strength and power, they matter, and ordinary people don’t matter so well. This has been fascinating and informative, but that’s it for today’s episode. I want to thank Stephen Hanson and Jeff Kopstein of William and Mary and UC Irvine, respectively, for sharing their thoughts on the assault on the modern state. Look for International Horizons on the New Books Network, and remember to subscribe and rate international horizons on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. I want to thank Claire Centofanti for her technical assistance, as well as to acknowledge Duncan McKay for sharing his song International Horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey saying thanks for joining us, and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.