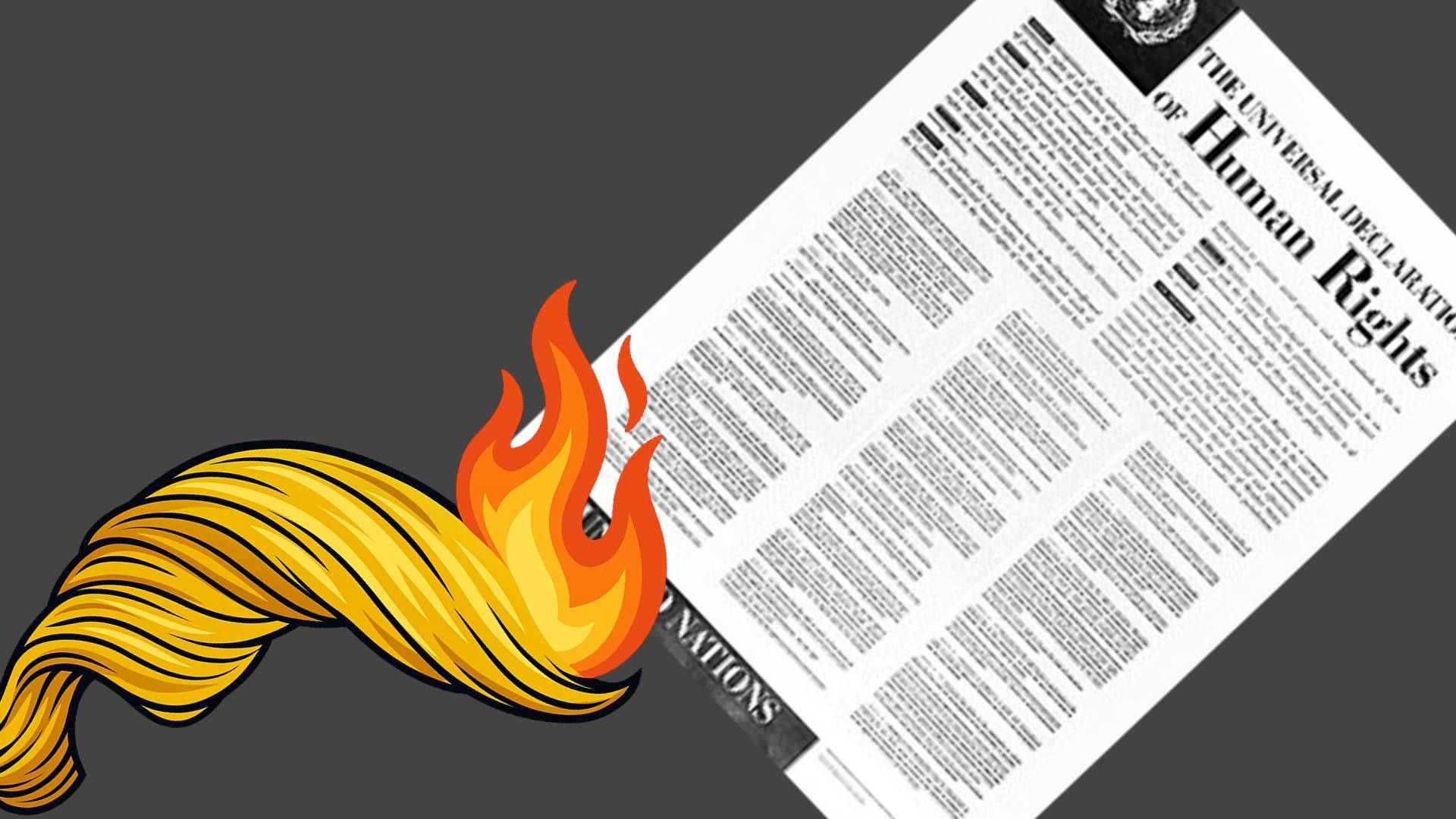

Human Rights in the Trump Era

In this episode of International Horizons, Kenneth Roth, former longtime executive director of Human Rights Watch, joins RBI director John Torpey to discuss Roth’s recent book, Righting Wrongs: Three Decades on the Front Lines Battling Abuse of Governments (Knopf, 2025), which reflects on strategies for defending civil, political, economic, and social rights in an increasingly complex international landscape. Roth explores the implications of Trump’s dismantling of USAID, the evolving challenges posed by authoritarian regimes like China, and the critical role social media plays in both exposing and enabling human rights abuses globally. Tune in to hear how Roth maintains optimism about the human rights movement and its continued fight against human rights abuses.

Below a slightly edited transcript of this conversation.

Transcript

John Torpey

One of the first moves of the second Trump administration was to dismantle USAID, the US Agency for international development. Many people regarded the attack on USAID as an assault on a liberal bastion of human rights promotion, and one lacking much political support outside the beltway. Its defenders saw USAID as an important humanitarian organization that bolstered American soft power around the world. The attack raised the question, what does the future of the human rights movement look like under a president defined by an America First agenda, who’s generally rather hostile to humanitarian efforts, even at times in his own country. Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. We’re fortunate to have with us today Kenneth Roth, the longtime director of the global human rights organization Human Rights Watch. He first assumed that role in the early 1990s and only stepped down a couple of years ago. He recently published a book reflecting on his experiences in Human Rights Watch called Righting Wrongs: Three Decades on the Front Lines Battling Abuse of Governments, published by Knopf in 2025. Thanks for being with us today, Ken Roth.

Kenneth Roth

My pleasure to be with you, John.

John Torpey

Thank you so much. So let’s start with a big picture question. You ran Human Rights Watch for some 30 years, since shortly after the end of the Cold War. I’m guessing that the Cold War was a tougher environment-I know that the Cold War was a tougher environment than the years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. And how would you say the balance sheet looks for human rights from this kind of long range perspective?

Kenneth Roth

Well, I mean, John, that’s a big question. Obviously, if you just look at governmental practice, the Cold War was an excuse for everybody to back the abuse of governments on their side. The end of the Cold War got rid of that excuse. But then we had this outbreak of of ethnic slaughter in places like Rwanda and Bosnia. You know, we survived that in parts of the world, and then George W. Bush’s War on Terrorism came after September 11, 2001, which became a new excuse to commit atrocities, to torture people, to throw them in Guantanamo.You know, things are obviously bad now, but this is also not the first time we’ve had Trump, you know, and we did survive the last Trump Administration. The other element though, you know, because the defense of human rights is not just about, you know, which governments are around, it also is a matter of a broader movement, and the human rights movement is much stronger today, much more diverse, much more widespread than it ever has been. There are now, you know, multiple human rights groups addressing virtually every country in the world. The communications technology has taken off when I started doing this work, you know, international phone calls were expensive. You had to travel places, you know, send mail, snail mail. It was hard to get information. And so things went more slowly. With the emergence of, you know, first email and and now smartphones and social media, it’s very difficult for abusive governments to hide anything. You know, it’s almost unthinkable that in today’s world, something like the Khmer Rouge could slaughter 2 million Cambodians, and we wouldn’t know for sure what was happening. So the prevalence of information, the difficulty of covering up atrocities, is a real boon for the human rights movement, and it enables us to learn about something today and try to stop its recurrence tomorrow, which is a big change from the early days. But obviously the autocrats of the world also were using social media to spread disinformation and hatred. So, you know, that’s, that’s a new challenge. So I mean, as I point out in my book, this is not a linear process. The battle for human rights is incessant. You win some, you lose. Some governments are always tempted to violate human rights, and our job is to tip the cost benefit calculation of oppression, to increase the cost of abuse, to make it more difficult to sustain.

John Torpey

So, you say in the book that the current, the greatest challenge currently, is really the rise of authoritarian regimes. And I wonder if you could say a little bit more about that and where you see that all going. I mean, on the one hand, people have talked about Trump as a kind of leader of a broader range of such countries across especially in Europe, but there are also signs that he’s galvanizing a certain amount of kind of opposition attention to that kind of politics in Europe, certainly.

Kenneth Roth

Well, John, I mean, actually, what I see as the biggest threat to the global human rights system is China, because it’s trying, it alone is trying to rewrite what human rights means. It doesn’t just violate human rights, which it does big time, but it’s actually trying to rewrite the rules, which is kind of a radical assault. But on the point you make about, you know, the global contest between autocracy and democracy, I think that, that is often misunderstood, and I describe this in the book, in that, you know, people assume that the autocrats are winning, but if you look at it from the autocrats perspective, it’s much more complicated. You know, first of all, the most visible autocrats, people like Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping are showing that autocrats don’t deliver better than democracy. They make big mistakes because they operate in an information vacuum. They don’t allow free debate, and so, you know, Putin will invade Ukraine, thinking it’ll be a cakewalk. Xi Jinping undermines the most vibrant sectors of China’s economy because he doesn’t control them. And when people see that autocrats serve themselves, not the people, they don’t want anything to do with it. And so we’ve seen in country after country where people live under autocracy, they want out. They want democracy. And we’ve seen, you know, masses of people coming to the streets, often at risk of being detained or or even shot in you know, Hong Kong, Thailand, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Iran, Russia, Belarus, Uganda, Poland, Nicaragua, Cuba. I mean, I can just go on, there have been many of these cases. They don’t all succeed. You know, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, they hosted the tyrant. Other places, the tyrants use brutality to stay in power, but the people make clear what they want, and autocrats see that as a hostile environment out there. Ironically, the biggest threat today is in the established democracies of the West, where people who feel left behind, they feel that they’re economically stagnating, that inequality is growing, that governments don’t serve them, don’t respect them, don’t hear them. They are the ones who are more ripe for the autocrats appeal. And I think the challenge that we face is to bolster Western democracies to ensure that they indeed do serve everyone, and also to counter the demonization of disfavored minorities, which is a favorite autocratic technique, including by Trump, as a way of trying to rally the base and simply say that whatever problem society has, it’s the fault of the immigrants, or it’s the fault of the gays, or, you know, you just pick the disfavored minority. And we need to push back against the set in a way that, to be honest, progressives have not been terribly good at because progressives have tended to favor a politics of identity, where they’re stressing everybody’s difference rather than stressing a commonality, a common interest in rights. And I do think we have to be more comfortable speaking about a national community where everybody has rights, rather than treating people as just a collection of identities, where they you know, each want their own set of rights.

John Torpey

I couldn’t agree more. I actually just finished a book about sort of anti racism and its excesses and problems. And, you know, I guess in a way, it flies in the face, in principle, of the kind of universalism that underlies human rights, it seems to me. But I think, you know, I’d be interested in hearing you say a little more about how you think we got into this particular pickle, and, you know how we’re going to persuade people on the left, you know, that they need to be patriotic, they need to be comfortable sort of defending their country and or saying that that’s what they’re doing, whereas they’ve tended to shy away from that. Well,

Kenneth Roth

Well, I think we got here because, you know, various segments of the society did face racism or sexism or homophobia, you know. So I think the identity politics of the left was responding to a real problem, but they’ve done it in a way that tends to exclude other people, you know, and and certainly, you know, many of the white working class Americans who rallied to Trump feel excluded by identity politics. You know, that’s why Trump is, you know, making so much hay with his campaign against vocism, you know, is playing on that resentment. But I think you know, as you note, progressives have to become comfortable, you know, speaking about the national community, and that doesn’t mean nationalism in the aggressive, militaristic sense, but by stressing that we all as a national community have rights, not simply because we happen to belong to an identity group, but because we’re Americans or Canadians or Europeans or whatever, you know, the nationality is, and progressives should be comfortable with it. There’s nothing wrong with promoting a national community where we are all rights bearers.

John Torpey

And where we are all aspiring to some kind of equality.

Kenneth Roth

Precisely.

John Torpey

That is the American promise, it seems to me. And in many ways, that’s been regarded as irrelevant to what’s actually happened, and I think that’s a problem. But in any case, you know, following up on this, since we’re in on this sort of general set of topics I heard you speak in a recent interview elsewhere about immigration, and immigration is obviously part of the set of issues that we’re talking about here, and who comes into the country and under what circumstances, and how can they become citizens, and that sort of thing. And you say something to the effect you’re said something to the effect that, you know, you have to have a robust asylum system, but that doesn’t mean you have to let in every, you know, de facto economic migrant who shows up at the border. And I think that’s another kind of case where the left has confused, you know, border regulation with some kind of racism. Yeah,

Kenneth Roth

No, I’m a big believer in the right to seek asylum. I mean, my father sought asylum when he was fleeing the Nazis and landed in New York. So it is, you know, it’s a right I deeply believe in. Today, I think, and oddly, the greatest threat to the right to seek asylum is this the ability of the far right to pretend that there are open borders and anybody can come in. And while there are, you know, some on the left who would love to see anybody show up, who can, you know, feel that this just a matter of of, you know, international justice, in fact, you know, every country does try to regulate who enters. And while there is a need in virtually every Western country for immigration because of demographic decline, you know, because there have been, you know, lower fertility rates. To do that in a controlled way is politically palatable. To do it in a way where the borders seem uncontrolled, is a recipe for the xenophobia that we see with Trump or Victor Orban or various representatives of the far right. So, you know, much as it would be nice to say letting people who are fleeing poverty, letting people who are fleeing climate change, you know, I understand the equitable justice there, but that is clearly more than the political market of the United States can bear. And if it is pushed too far, it jeopardizes even people who are fleeing persecution or war and have a right to seek asylum. And that’s what we’re seeing now where Trump is saying, you know, no, you know: no, you don’t even get into the United States, go wait in Mexico, maybe forever. You know, you don’t really have a right to show up at the border and seek asylum. And that, I think, is, you know, a big risk of not being willing to say it’s fine for a nation to control this borders, you know. Now let’s discuss who gets to come in

John Torpey

Again, I couldn’t, couldn’t agree more. And, frankly, before we were having this conversation, I never really thought we’d be addressing these sorts of issues, because I always think of Human Rights Watch as a kind of international organization, or one that’s focused, you know, basically on the rest of the world, and of course, this has changed very much under your, you know, leadership and Human Rights Watch came to be an organization that paid a lot of attention to the United States, and that was a big part of your tenure, I think. so that’s correct.

Kenneth Roth

That’s correct. I mean, if I could just say John that…

John Torpey

Sure!

Kenneth Roth

That’s important as a matter of principle, that Human Rights Watch looked at everybody, wherever there were serious abuses, we would report on them and condemn them, try to change them. So you can’t exempt the United States from that. Indeed, the United States, by the end of my tenure, was the organization’s largest country program. But also this was not just for show. Because, well Human Rights Watch ordinarily operates in countries where the legal system isn’t functioning as a check on executive misconduct. And you would say, well, the United States has a strong legal system. ACLU is a great organization. Why do you need Human Rights Watch? Well, we found that there are certain areas where the courts are not effective. Immigration is a big one, because most undocumented migrants will not risk going to court. Criminal justice is actually one too, because while people get a fair trial in the narrow sense, if the issue is, say, systemic racism in police practices, in the setting of bail and in plea bargaining, no single defendant is able to bring that up, and you need the Human Rights Watch methodology of investigating a pattern of abuses, reporting on it, and putting pressure on the political branches of government to fix it. So that’s the work we tried to do in the United States.

Speaker 1

right?

John Torpey

So back to our current situation, and where the United States fits into this. I mean, you know, it’s not news to you that the United States in the last week or so, voted at the UN with Russia and North Korea, and, you know, our traditional antagonists and against our European, long time European allies. And it’s hard to conclude that this is anything other than a kind of fundamental break. I mean, you have a certain professional optimism about these things that may require you to, you know, sort of say that this is not the end of things, but it does seem that even the Europeans have come to think of themselves as now being a kind of enemy of the United States, and that’s a fundamental transformation. So I wonder how you would say that affects, you know, the Human Rights environment.

Kenneth Roth

Well, I mean, John first, let’s put this in perspective. I mean, the United States forever, has voted against all of its democratic allies, or most of them, when it comes to Israel. You know, it used its veto at the Security Council. It would vote against any criticism of Israel at the UN Human Rights Council, the United States was a virtual pariah when it came to defending Israel, regardless of war crimes in Gaza and the West Bank. So we’ve seen elements of this in the past. What’s new now is that this just took place with respect to, you know, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the systematic war crimes being committed there, the war crimes that five minutes ago the US government was vehemently opposing, and suddenly the president changes and and the US is, you know, going neutral or even opposing efforts to hold put into account. Now, you know, this is Trump. We’ve, we survived the first Trump term, where, you may recall, he withdrew the United States from the UN Human Rights Council. You know, something that nobody does voluntarily, and we did fine without him. You know, in fact, it may have been easier because he wasn’t voting against us. He just wasn’t there. So for example, when it came time to to try to condemn Venezuela, if Trump had been in the lead, it would have been viewed as an imperialist effort. But because a whole group of Latin American democracies, plus Canada, came together in what was known as the Lima Group, it looked like a principal defense of democracy against Maduro’s repression. So that was, you know, an example of getting things done without Trump. You know, similarly, when it came to the Saudi led coalition’s bombing of Yemeni civilians, we worked with the Netherlands and other European countries, and successfully, you know, monitored and condemned what was happening and visibly saved lives. Because we, when that, when that scrutiny was finally lifted, the killing of civilians doubled until the ceasefire finally went into place. So, you know, we can get things done without the US. I think the challenge now is, you know, Trump is clearly in a powerful position with respect to Ukraine, if for no other reason than us, military support has been essential for Ukraine’s defense. It’s essential for a lasting peace because, you know, Putin just wants a temporary cease fire prevent Ukraine from rearming while Putin actively rearms, he would then re invade at some point in the future, because presumably, you know, when Trump steps down and then continue on his quest, which is what this is really about. It’s not about, you know, a bit of territory in eastern Ukraine. It’s about snuffing out Ukraine’s democracy so it can no longer serve as a model for the Russian people who otherwise must live under autocracy. So, you know, that’s where it stands. And I think our best strategy with Trump is to play to his fragile ego, you know, to play to his self image as a master negotiator, and if he, you know, accepts the narrow Putin ceasefire without providing a U.S. backstop to European peacekeepers on the ground, he will have been bamboozled by Putin. You know, this will be viewed as, you know, the deal, the rotten deal that naive Trump agreed to. He will be the Neville Chamberlain of the 21st century. It’s only by ensuring a sustainable peace, you know, with the security guarantees that Ukraine rightfully seeks, that this will be seen as a good deal. And I think that’s our best bet, is to play to Trump’s vanity, his ego, and make it clear that that will not be satisfied unless he does, you know, the right thing for the wrong reasons.

John Torpey

right? So another question about kind of contemporary American politics and human rights environment, and that is I started out with, you know, mentioning USAID and the attack on USAID. And I, you know, made point that this is a problem, certainly for people inside the beltway and for many people who understand what USAID does in the world. But you know, Americans are not necessarily all that enthusiastic about an organization like USAID. They think we spend far too much money on humanitarian assistance, even though they misunderstand how much that actually is. But this is something that Trump has, you know, used as a campaign issue, certainly. So I wonder, you know, what you would say about popular preferences in regard to concerns about what’s going on in other parts of the world that sort of lots of ordinary people don’t think is part of their problem, really.

Kenneth Roth

Yeah, and I mean, Trump plays on this narrow sense of America first. Just leave the list of the rest of the world alone. No need to help, you know, no need to support democratic development there. And that’s incredibly short sighted. Because, you know, even though Trump feels that the United States is the superpower, and even though it does have unparalleled military and economic might, its relative power has declined. If you look at the United States in the world today compared to 20, 30, years ago, the world is a much more multipolar place. The US has less clout, and that is the great value of alliances. That’s the great value of, you know, of having common, shared democratic values. Because it’s not just the United States alone. When the United States operates with other democracies in Europe and Latin America, in Africa and Asia, and Trump could care less about all of that. And I think he is enfeebling the United States by turning it into, you know, a contest where everybody gets their own, you know, they only look after them for themselves. They only look after themselves, and the U.S. will be worse off in those circumstances. So I think you know, it’s important that the the human rights movement, the Democratic Party, you know, that opposition to Trump articulate why it’s not in America’s interest to take this incredibly narrow perspective that is guiding Trump’s foreign policy.

John Torpey

And how do you think the rest of the world is, in fact, responding to Trump? I mean, insofar as they have, you know, their own interests, and have tended to step away from his, his approach to things.

Kenneth Roth

Well, I mean, it depends who we’re talking about. I think the autocrats of the world are, are, you know, clinking glasses of champagne because Trump is defunding the human rights defenders, the democracy promoters, the independent journalists that are the bane of their existence. In terms of Europe, it’s actually seems to have solidified Europe. They clearly are now spending more on their their military defense, but they also seem to be coming together more in defense of their democratic values. I mean, Trump has done more to reverse Brexit at a political level and a security level than anything else so far. Because, you know, suddenly Britain and the European Union have in common the need to defend global democracy as Trump moves away from it. So it’s a complicated moment. Also, we shouldn’t ever assume that what Trump does today is what he’s going to do tomorrow. You know, this is a guy who is loyal only to himself, who can turn on a dime if he feels that it serves his narrow self interest. He has no principles. And so, you know, yes, today he’s turning his back on the world. Who knows what he’ll do tomorrow?

John Torpey

right? So, I mean, human rights has long had, you know, sort of varied aspects, you know, the civil and political rights on the one hand, and economic and social rights, broadly speaking, on the other. And I wonder if you could talk about how the concern with those different areas within Human Rights has developed over time.

Kenneth Roth

Well, the two sets of rights are codified in two parallel treaties that emerge from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and they are seen as interdependent, because if you don’t have civil and political rights, which is how you hold a government accountable, how you influence its policies, that’s when governments tend toward corruption, toward vanity projects, toward misallocating available resources for themselves rather than for the people most in need. And so if you want to achieve economic rights by, you know, promoting access to health care, to education, to housing to jobs for the people who are most impoverished, the worst off segments of society, you also need to have civil and political rights. Now what’s interesting is, traditionally, like during the Cold War, people would say, Oh, the West promotes civil and political rights, the Soviet bloc promotes economic and social rights. Now that turned out not really to be true. I mean, the Soviet bloc was incredibly impoverished. It was doing a terrible job of providing for people’s economic needs. Today, there’s a variation of that in China, but, but it’s different in that, you know, China obviously doesn’t tolerate civil and political rights because, you know, wouldn’t dare hold an election because it would lose. You know, it wouldn’t dare allow an independent media, independent civil society, independent judges. It wants to have a dictatorship of the Chinese Communist Party. So we’re not surprised that China doesn’t tolerate civil and political rights. But many people sort of assume that China promotes economic and social rights. It actually doesn’t, and this is where China’s effort to redefine human rights standards comes into play because Xi Jinping wants to say that it really is all about just expanding the economy. If GDP per capita is growing, then that’s satisfying his human rights obligations. And that’s not what economic rights ask about. They ask, are you using available resources to progressively realize the economic needs and meet the economic needs of the worst off segments of society? And Xi Jinping doesn’t want you to ask about, you know, how are the Uyghurs, faring? How are the Tibetans faring, you know, how are rural Han Chinese doing, you know, when they are sequestered behind the hukou system? So they don’t want those individual rights oriented questions either. They want to perceive rights as just about the collective, not about the individual, when that’s the opposite of what human rights are about. That’s why I view China as the greatest threat to the global human rights system, you know, quite apart from its repression at home.

Speaker 1

right?

John Torpey

So before writing this book, you ran Human Rights Watch for almost 30 years, one could imagine that might be a kind of high burnout sort of job. So I’m curious, you know, reflecting on some of the things you said just now, you know, how you manage to maintain kind of optimism in the face of what is, you know, unavoidably, a kind of relentless problem, or set of problems. And so I’m wondering how much that has to do with sort of taking the long view, which often seems to come into your answers. So, curious, you know, what allowed you to maintain optimism over 30 years?

Kenneth Roth

Well, I mean, John, what I mean, obviously, I’m dealing with people’s misery all the time, and at a level that’s depressing. You know, there’s just no avoiding that. But I knew that I was collecting their stories. I was because I could deploy that information to put pressure on governments to curtail their atrocities. And there was a purpose to this which I knew would have an impact. And I try to, this is what I show in the book. I mean, the book kind of pulls the curtain back, shows the strategies that we use. And the point is to, you know, debunk the critics who think that the defense of human rights is kind of a nice, well meaning thing, but isn’t terribly effective. And I just tell story after story of impact, how we were playing hardball, how we were forcing governments to behave better. And that’s what kept me going, because I saw how we can make a difference again and again and again. And I hope people come away from my book with optimism. It’s not a pessimistic book, you know. It obviously touches on on horrible problems, but it shows how we try to fix them, and how we often do fix them. And that is, I think, the, you know, the lesson that keep me going, and I hope it will make for a more engaged public as they read my book.

John Torpey

I was struck by that. I was struck by that myself, that it’s not a pessimistic book, and it is about the kind of techniques that you develop, which, interestingly to me, over time, had a lot to do with a certain kind of research, what sociologists, the kind of work that my people tend to do. So, so it is an optimistic book, and I want to urge people to go out and get it. Is called Righting Wrongs by Kenneth Roth, the long time Executive Director of Human Rights Watch. I want to thank Ken Roth for joining us today and talking about the past, present and future of human rights. Look for International Horizons on the New Books Network and remember to subscribe and rateInternational Horizons on Spotify and Apple Podcast. I want to thank Claire Centofanti for her technical assistance, as well as to acknowledge Duncan McKay for sharing his song International Horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey saying thanks for joining us, and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.