The Climate Crisis as a Problem of Collective Action

In this episode of International Horizons, Professor Dana Fisher, Director of the Center for Environment, Community, & Equity (CECE) and Professor in the School of International Service at American University, discusses with RBI Director John Torpey her approach to dealing with the climate crisis. Fisher explains how the climate crisis is really a social crisis for which collective action seems impossible. Fisher further explains the actions of the players involved in resisting the problem of climate change and their interests in doing so. Finally, she explains how important it is to approach change through strong communities and the solid infrastructures that support them.

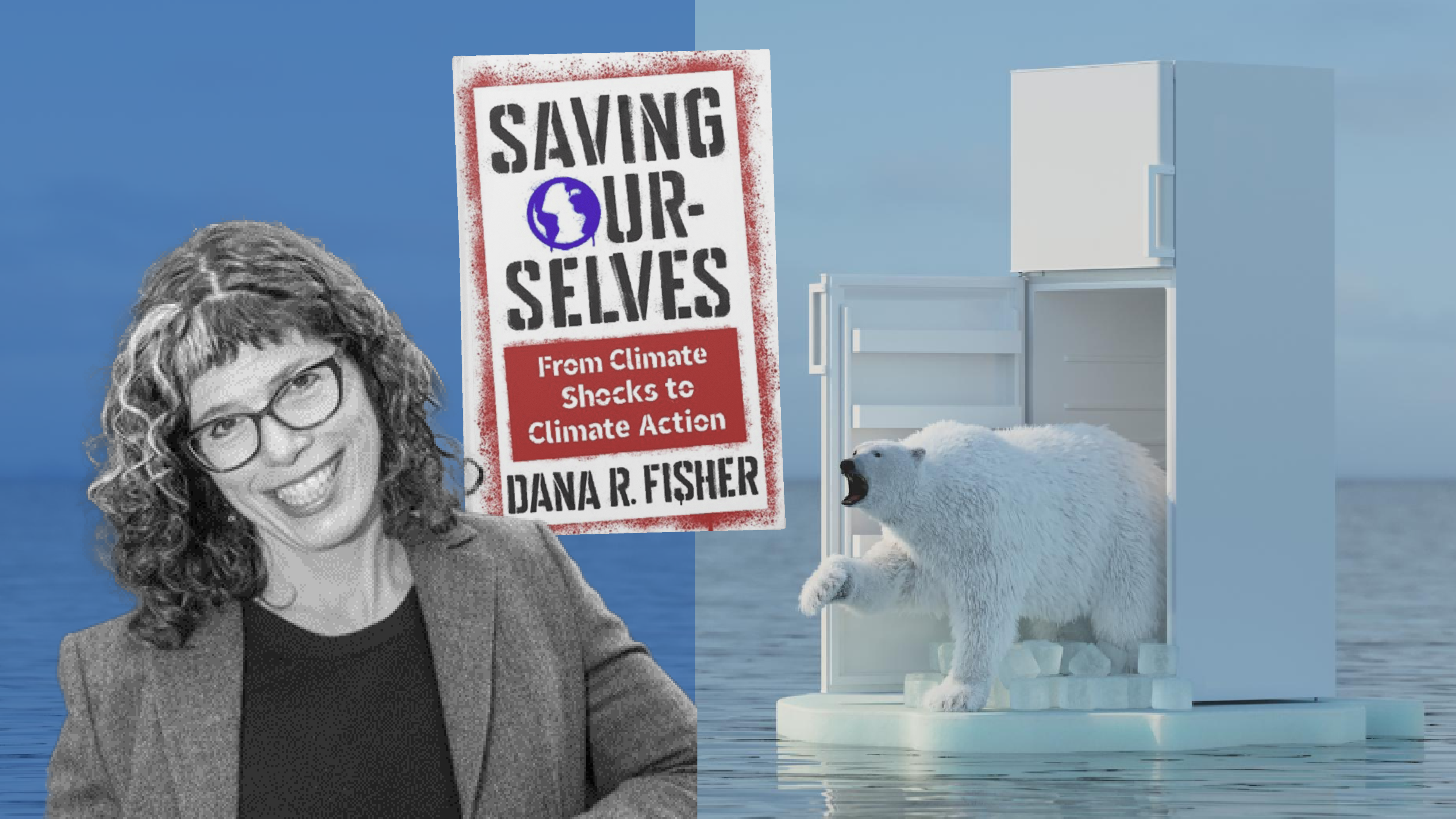

Fisher is the author of Saving Ourselves: From Climate Shocks to Climate Action (Columbia UP, 2024).

John Torpey

We probably all recall one of the most dramatic climate-related events of the recent past – the difficulties we had breathing an eerily orange air last summer as the smoke from Canadian wildfires wafted down to the New York City area and hung around for days before being blown away. We have also already heard that ocean surface temperatures this year are well above normal, again, and that we should expect a major bleaching of the coral in the seas that sustain so much other sea life. Can we get a handle on climate change before it is too late?

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Today, we discuss the climate change situation with Dana Fisher, the director of the Center for Environment, Community, and Equity and a professor in the School of International Service at American University. Her books include Activism Inc.: How the Outsourcing of Grassroots Campaigns is Strangling Progressive Politics in America (2017) and American Resistance: From the Women’s March to the Blue Wave (2019). Her most recent book is Saving Ourselves: From Climate Shock to Climate Action, published by Columbia Unviersity Press this year. Thanks for being with us today, Dana Fisher.

Dana Fisher

Thank you so much for having me, John.

John Torpey

Great to have you. So you have a new book out, as I’ve just said, about the climate change crisis and how we are going to address it. So maybe we could just start by having you outline a bit your argument in the book?

Dana Fisher

Sure. I mean, in essence, the argument in the book is, the climate crisis is social crisis. To address it, we’re going to require and need social changes to get there. I talked specifically in the book about how the types of social changes that are needed to address the climate crisis at the level required involves systemic changes that will address all parts of the way that we live our lives. And at the moment, the climate crisis is bad, it’s getting worse, nothing we have done so far has brought us to the level of social change that we need to address the problem. And to get to the type of systemic changes that are needed will require what I call in the book an anthro shift, which opens up windows of opportunity for real innovative social change. And that will be driven by personal experience of risk, which will come from people experiencing the climate crisis firsthand, for example, experiencing the wildfire smoke that we saw last year, or experiencing extreme heatwave extreme weather events, such as the flooding in Pakistan, or the flooding that we’ve seen in the Middle East recently, or the atmospheric rivers that we’ve seen on the west coast, the list goes on and on. But basically, all of those things will motivate individual citizens to take action, and the most likely way to or the most likely path through to the types of outcomes that are needed socially, that will address the climate crisis is pressure coming from the civil society sector that finally gets business and governments to take the types of actions that will be somewhat painful, but needed to get us to the other side of the climate crisis.

John Torpey

Right. I mean, you say that things are going to have to get kind of dire. Not the most pleasant message to read. But I mean sociologists, you and I are sociologists, sociologists, I think probably would see this as an enormous collective action problem, right? We all experience these unpleasantness individually in certain ways. And it’s also hard to see and you say it’s not obvious what individuals really can do in terms of changing their habits and not buying this or not eating that. I mean, those may make a contribution, but then they’re not really going to address the problem. So can you talk a little bit about that collective action problem?

Dana Fisher

Sure. I mean, the problem right now, there are many aspects to this problem, but when we get down to the kind of the brass tacks of it, it’s true that we’ve all been, you know, in some ways, free riding on the fact that our lives are relatively comfortable, at least here in the developed world. For many people lives are comfortable, we have energy, we have resources, we have ways of getting around. And you know, and we have bigger concerns, right? And actually, if you look at data on what is driving people’s opinions around elections and who they’re going to vote for, climate change in the environment does not rank particularly high. But we’re really not recognizing the crisis that is coming, that is almost knocking on our door, you were mentioning a number of indicators that we are heading towards what the natural scientists say, is likely to be tipping points on multiple levels that can cascade into real disaster. And I don’t mean, you know, disaster for one community or one area like a hurricane Sandy, I mean, global disaster. And that’s not my research. That’s my summarizing research from the natural scientists but as a result, what we know is that we really have this this problem of getting everybody to take action now before it’s too late. And that is a real collective action problem, it’s particularly difficult, because in the case of climate change, addressing the problem means basically shifting away from fossil fuels, it’s become very clear, lots of people are talking about it, but whenever the rubber meets the road, and we have decision making in the form of like an international meeting, like they just recently had last fall, or I guess, like the meeting that they had in November in December, which was the most recent round of the climate negotiations. Even now, the government’s can’t agree on a phase out of fossil fuels. Even now, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which is the UN body that advises given scientific information, which I contributed to in the last round, even now, we’re not allowed to call the interests that are pushing back against the types of changes that are needed, we’re not allowed to call them out as fossil fuel interests, even though there’s ton of tons of evidence that that’s who it is, we had to call them vested interests in this most recent round of scientific assessment, because of the role that they play, and the privileged access, they have to resources and power internationally, nationally, as well as in our local levels, anywhere where fossil fuel interests exist, they are pushing back against any social change. So that makes it even harder. So it’s not just a collective action problem, like a lot of people want a free ride, because life is comfortable. It’s also there are organized interests that are consolidating their power, and consolidating their control, because they want to maintain their access to natural resources, which they get, you know, for pennies on the dollar, and access to power in terms of access to people in Congress and to other elected officials, that helps them continue to have this access, right. And so it’s, you know, it’s a vicious cycle, and we have to break it and breaking it is not easy. And it’s not just an American problem. It’s a problem that we see around the world, particularly anywhere that has natural resources that are being extracted to fuel our industrial processes.

John Torpey

So you write about this a little bit in the book, and it’s part of the explanation of what’s going on. But who exactly are we talking about? I mean, okay, you could only call them vested interests in the report, but you can call them what you want here.

Dana Fisher

Yeah, they are fossil fuel interests. I mean, so they, first of all, they’re all the companies that are extracting fossil fuels, right. So that is, you know, your oil companies, your natural gas companies, your coal companies, although actually, I mean, coal is losing out here and coal… I’ve been studying climate policymaking for the entirety of my career. My dissertation, which became my first book back in 2004, was called National Governance and the Global Climate Change Regime, and it specifically looked at the Kyoto Protocol and domestic responses to it. And during that time, I interviewed numerous people who were in the Federal Government, who talked about how it was really kind of easy to understand how we could address climate change back then, I mean, this is in the 1990s, like late 1990s, all we needed to do was phase out coal. So the writing was on the wrong wall on coal for a long time. I mean, coal is the most carbon intensive of all the fossil fuels. So it was the easiest one to recognize. And if you just phase it out back in the day, back in the 1990s, if we had just stopped burning coal and shifted to natural gas then, we would have addressed a lot of the emissions problems that have continued to build up and exacerbated the problem. Today, though, we’re talking about, you know, we have had this big, natural gas boom here in the United States, thanks to fracking technology, which means makes fracking possible around the country. And there are a number of states that do fracking and they’re also those states that are experiencing these unexplained earthquakes that never happened before because of the way that they’re affecting what’s going on underneath them. You too?

John Torpey

I live in New Jersey. I grew up in New Jersey, too. It’s not a place I associate with earthquakes, but we’ve, as you may know, had a series of them over the last I don’t know a couple of weeks now. I mean, first was I mean as far as I know first was a relatively big one in the four point something range. And then it’s just been a series of two point something aftershocks, after that now I haven’t heard anybody say anything about this has to do with fracking but it’s a little weird…

Dana Fisher

Yeah, no, no, it’s completely weird I know. So in in New York State fracking is banned. But in Pennsylvania fracking is not banned. And I know for having grown up in Pennsylvania and having had a house in New Jersey for a number of years, I know that Pennsylvania and New Jersey touch one another. So I actually I’m not sure how that plays out. So I won’t, you know, I’m not a seismologist, so I’ll just say that there has been you know, that’s how people talk about it in in that field. But anyway, when I call out fossil fuel interests, the thing that I think is worth noting here is that it’s not just the companies that are extracting the fossil fuels, granted, they are, they have to be called out and they have to be explicitly called out because even today, there was just a Senate Joint Committee Report released this week, specifically talking about how oil companies continue to obfuscate that and try to redirect the general public away from understanding the role that oil and oil burning, is playing in the climate crisis. And so they’re very, very, very responsible for what’s going on. But there’s a whole industry that’s connected to fossil fuel extraction and expansion, all the people who build the pipelines, all the people who do the mining, all the people who process everything with petrochemicals, we have plastic, so it’s a very, very large, you know, industrial complex that we’re talking about, which is why I call them fossil fuel interests, not just fossil fuel companies. But even obviously, the fossil fuel companies will be, you know, the top of that industrial complex for sure.

John Torpey

Right. I mean, this is the next thing I really wanted to ask you. I mean, it’s relatively clear, I suppose, what we might call the social base of the fossil fuel, whatever complex is, but what’s the social base of addressing the climate change issue? I mean, it’s generally tended to be regarded as an issue for well, it’s relatively well off populations, but the labor movement, you sort of argue that the labor movement should be brought into this whole mix. And there are a lot of people whose jobs depend as you were just suggesting, on kinds of fuels that are inimical to our self interest. So, how do you deal with the fact that people feel like their jobs may be at risk, if there’s going to be agreed transformation?

Well, I would just say this, that, um, these are, these are really good questions. And these are questions that actually the Biden administration has spent a lot of time thinking about. And at this point, if you look at the funding coming out of the Inflation Reduction Act, which was a big act that was passed, that has a whole bunch of climate and clean energy efforts built into it, but it’s, you know, it’s more than that. One of the things that the Inflation Reduction Act is doing is investing in energy dependent communities, those are the communities where they have a high proportion of the population, they’re employed in the energy infrastructure. So that could be extraction or processing, right,and what they’re doing is they’re actually specifically funding, helping to train people who have those jobs to redirect into other kinds of careers. So I would just say, I mean, there are lots of things that we can do to criticize the fact that the Biden administration could do more, but a lot of what they’ve done has been extremely innovative, and very forward thinking and very progressive, and is certainly the most we’ve seen anywhere in the world.

Dana Fisher

With regard to the other side, I would just say that well, it’s very clear, it’s very clear that concentrated interests and how that trickles down to looking at the people who are working within these industries, who are part of this kind of the dirty energy sector, which we need to move away from, but there is growing, there’s growing people working within the clean energy sector, the problem is right now that they tend to be, we tend to see the, you know, businesses as being bipolar, because we have some businesses that are pushing very hard for a clean energy transition, because they’ll make money and be profitable, and also help save the planet. But then there are all of those groups, there are no, they know that the writing’s on the wall in terms of there being a fossil fuel phase out coming. So they’re doing everything they can to squeeze out as much carbon to be processed as they possibly can, you know, drilling it, refining it, burning it and making money off of it. So there so you can imagine that there’s going to be a unified force within the business sector. So instead, what we need to do is look to the civil society sector, which does include labor. And one of the challenges right now with labor. Is that labor currently tends to be more connected to companies that are on the dirty side of the transition, right that are using, using fossil fuels or, for example, are making cars that burn fossil fuels. Historically, or I guess it’s not really that long in the past, but currently, many of the factories that either build the batteries or build, you know, vehicles, their electric vehicles, right, clean energy vehicles if you want to call them that, are not unionized. And that is a real shift. And what that basically means is that labor and unions tends to be on the other side. I mean, there’s been lots and lots of media all about how Elon Musk doesn’t want to let Tesla factories unionize. But recently, we’re starting to see a shift there. But as a result, these collectives, these natural collectives, like labor, which you would think would be in, you know, working with those who want a clean energy transition have not been on board. And it is true that historically the climate movement comes out of the environmental movement, which tends to be relatively privileged, white, highly educated, we’re seeing a real shift there and we’re also seeing some move to connect with the the environmental justice movement, which has tended to come from communities of color and communities more impacted by environmental damage, we see a climate justice movement coming out of that, which is where the, what we call frontline communities, those that communities are going to be hit first and hardest by, you know, at least first with, you know, climate shocks when they come because they are communities of color, they are poor communities, they are communities, where they can’t afford to bring in, you know, the types of technologies that might help them to protect themselves. And so we’re starting to see more collaboration between these groups that work, you know, across identities, across orientations, across class, educational backgrounds, etc. But a lot more is needed, so that we’re just starting to see that, but there’s absolutely more need for that kind of connection.

John Torpey

Got it. So it occurs to me, as you talk that there might be a sort of parallel here with the tobacco experience, are there lessons from how big tobacco got sort of taken down for the climate movement? Is that a thing?

John Torpey

Well, I mean, yeah, and I’m just, I’m gonna just pull up here. I mean, so if you haven’t read Merchants of Doubt, which Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway wrote, which came out many years ago, which specifically documents the way that the folks who were, what they didn’t call greenwashing back then, but the folks who were actually protecting tobacco from policy makers and from written, you know, regulation, and from the information about how tobacco causes cancer, getting out and having an effect on people’s consumption of tobacco. There it is. Alright, so you know, so what’s interesting here is that when this book was published, this book was published originally 2010. It was quite groundbreaking. And then since then, Naomi and her postdocs and graduate students have published a whole bunch of pieces around what they call kind of the Exxon new papers, which is through FOIA requests to look at how much fossil fuel companies and oil companies knew about the climate crisis in a similar way, right. So tobacco companies knew for many years, that tobacco smoking, tobacco causes cancer, and they claim that they didn’t, and they use the media and marketing to distract people who are smokers from any information about how there might be negative health consequences to smoking. And the people who actually worked for the tobacco industry, ended up getting redirected and reemployed by fossil fuel interests and had been used to obfuscate as I said before, I mean, in fact, as I said, there were there were congressional hearings over the past few sessions of the US Congress, the report just kind of came out to show that many fossil fuel companies knew about global warming and the dire consequences of burning fossil fuels, decades and decades ago. And they also hired people to advertise and redirect and distract the American public and globally, the public, from knowing about this and worrying about it. And now we see I mean, it’s interesting, I’m on a review panel right now for another country, and I just was reading a proposal for a project that seems so innovative, and it’s all about helping to use indigenous knowledge as these countries are starting to build floating parts to their cities, right? Because sea level rise is projected to be so bad in parts of the world and in fact, their their conversations now about how bad it’s going to be here in the United States, particularly on the East Coast, that a number of cities are starting to invest in the technology, just expand their cities, and have them float so that when sea level rise happens, they’ll already be floating. And that won’t affect the infrastructure. It’s fascinating. But the fact that they’re actually starting to really like invest billions, if not billions of dollars in this is really, it’s something that we as general public don’t really understand and don’t really recognize, because everybody who is involved in planning and thinking it, you know, in terms of thinking forward in terms of understanding what’s coming, is just preparing for an onslaught from climate change. And we, as a general public need to do something about it, to help to push so that we don’t just prepare to adapt. I mean, I really would like to think that my kids and my grandkids aren’t going to be living on floating, you know, islands in the future. But that’s where we’re going if we don’t do something about it.

John Torpey

So Venice is everywhere…

Dana Fisher

Venice is gone and everywhere else. I mean, because Venice has to figure out what it’s going to do. They’re doing a much better job in Southeast Asia of using floating technology. In fact, there’s a word that as I was reading this proposal, I learned a new word, and I can’t remember what it was. But it basically means communities living on the water. So it’s like, was it called Waterworld, which was that not very good film by Kevin Costner that came up many years ago? Yeah, that’s basically that.

John Torpey

Okay, well, glad somebody’s thinking about these things, I guess…

Dana Fisher

I think it’s fascinating, I have to say, it’s really interesting to think about how you can use a lot of indigenous knowledge because certain indigenous communities have lived in on, you know, in island communities that connect across multiple islands. So they do, plan and live their lives floating in a lot more ways. And so it’s, it’s really fascinating to think about that, you know, as a sociologist at, that’s not the world that I want to live in. But it’s nice that there, there are some cultural Heritages that we can build off, right, something.

John Torpey

Right. So propose a world that you might want to live in. So the politics of this Democrats have constituents who work in the fossil fuel industry, too, and they have to be concerned about that I was struck by one of the comments I mean, quips I might even say, in the book about how democratic comes out of a previous book, I guess, but sort of Democrats are putting down side while the Republicans are ceding the ground, I think, is the way you phrased

John Torpey

cultivating the grass and I mean, I suppose others have made this kind of critique of the Democratic Party is too much with sort of membership organizations that don’t involve really boots on the ground, so to speak. And so I wonder, insofar as we can assume that the Democratic Party is more likely to be the political base for environmental climate change sort of movement, how are they going to do better and figure that out? How are they gonna get those boots on the ground around this kind of question?

Dana Fisher

Cultivating the grass…

Dana Fisher

I mean, that’s a really important question, John. In fact, there’s so I’ve written two books that talk about and analyze, in some cases, you know, my book Activism Inc. which came out in 2006, specifically, uses data collected from the Democratic Party versus the Republican Party, and talk about their different ways that they build or don’t build local infrastructure. And that’s where the original quote about laying sod versus cultivating the grass comes from. And unfortunately, when I wrote my last book, American Resistance, which came out in 2019, there nothing had changed, which is one of the reasons that we saw the resistance form outside of the party, because there was no infrastructure there to build upon. So the challenge to Democrats is really quite substantial, real and important and it actually connects to some of the findings, the main findings and suggestions I have at the end of the book. At the end of the book, I talk about how we’re going to actually work together and how we should think about getting involved and helping to save ourselves, and one of the things is about cultivating community. Cultivating community is about building on relational context in our communities, building true solidarity with other folks and other movements, and also getting embedded on community. And I compare the climate movement today to the civil rights movement that was so successful so many years ago, although obviously still more work is needed, no question about it. And we know from research on the civil rights movement, that the movement then was very much embedded in the black community through the black church, and even the folks who were engaging in civil disobedience, while the elders did not really approve or support of a lot of the tactics they were using, they were housed, supported and protected by the black church. We don’t have a black church right now, on the left will mean, we have, you know, there are some religious groups, but there’s just a lot less infrastructure, whereas the right has a lot of infrastructure, and they work very hard to cultivate and support it.

Dana Fisher

And that’s a real problem. And I think that, you know, as I’ve been doing my book talks, I’ve spoken with many people around the country about where we’re going to find the capacity to build this kind of infrastructure, which is really needed for not just saving ourselves from the climate crisis but for also saving our democracy. And one of the things that I’ve been talking with a lot of people about is not just looking for more progressive religious communities, religious organizations, but also schools, although schools are, you know, are having some problems right now, but also libraries, which are a site and every community for learning and education. And I actually am working with my center on a project where we’re hoping to partner with the DC public libraries to look at how climate information can be distributed in a more effective way to communities, based on the the orientations and interests of the community, particularly the demographics of the community, because there’s a lot of climate misinformation out there. And providing actual information that is, legitimized by the library is a really great way for people to learn more about what’s going on, as well as connecting their community. And one of the things that we don’t think enough about, it’s the way that the library does provide a hub for all sorts of things. I mean, during the pandemic, the library was where we got our PPE, it’s where we got our COVID tests, right? It stayed open, and let us pick up books in really new and innovative ways. And there’s a lot of capacity there. So there’s work to be done there just in general. Unfortunately, what I observed back when I was doing my research in the early aughts is still a problem with the Democratic Party, and the Republican party still is doing a much better job of that. But you know, one of the things that I talked about in the book is how people will start to mobilize because of their personal experiences with climate crisis. When that happens, I’m encouraging everybody to cultivate resilience in their communities in terms of social resilience that can, you know, and get connected in your community better so that you know who to call if your house is flooded out, if some, you know, a tree falls in your house, if you need support because you’re experiencing climate shock. And the places where you’re going to get that support are really friends and neighbors and people in your communities, it’s gonna be a lot harder for people to parachute in, and provide assistance if we’re dealing with disasters. So I think there’s lots to learn. But I do think there are places we can look, but we’re gonna have to do some time, spend some time investing in building that out. And I hope that, you know, my book might suggest ways to do that.

John Torpey

Right. Well, I thought the business about community building or building, not community building exactly, the building on community I thought it was an important point that you made. But a lot of the book is, actually not a lot, but some of the book is about the kind of tendency towards the emergence of a kind of radical flank. And since you call yourself an apocalyptic optimist I’m curious what you see happening there? Why is this happening? And why is it happening now?

Dana Fisher

Sure, well, so I mean, I call myself an apocalyptic optimist, not because of the thinking about activist tactics, but rather just because…I’m an apocalyptic optimist, because my vision of how we’re going to address the climate crisis involves some real pain and suffering for the general public. And that’s based on the realistic expectations and predictions of natural science and atmospheric science. That mean, like you mentioned, the beginning, we are off the charts in terms of temperature. Here in the DC area yesterday, we broke another record with temperatures in the 90s. It’s what the first week of May, I mean, it’s not even the first week of May, right. And we had temperatures in the 90s last week, too. And we have today, it’s beautiful outside, but it’s gonna go right back up again. So 2024 is, you know, is an El Niño year, the end of an El Niño, so we would expect it to be warmer, but it is so much warmer than expected. See, you know, see temperatures are warm, we have coral bleaching, the poles are melting… I mean, so, you know, the apocalypse is nigh in some ways. And you know, we need to be realistic about what’s coming because because the best thing we can do at this point is prepare ourselves and think about how we’re going to adapt and support one another as it happens, because it’s too late to stop a lot of what’s coming. That’s the apocalyptic part.

Dana Fisher

The optimistic part is really about how I do believe in people power. And I believe that people will rise up as they experience climate shocks firsthand, they will get angry, and they will do something about it and that will lead to opportunities for decision making, and for the people in power to make the right decision in terms of getting us off fossil fuels, and hopefully, cutting down on the the pain and suffering that’s going to come from the climate crisis. And how that plays into activism is that, you know, I spent a lot of time talking about the civil society sector and climate activism, and kind of the ecosystem that is climate activist. And then I spend time talking about this growing radical flank mean, we know from social movements that as movements grow, and you know, continue on, people, either, you know, they either demobilize, they give up, or they radicalize. This is, you know, this is standard for any social movement. In fact, during the period of the resistance when I was working on the book, American Resistance and I was watching what was going on with people mobilizing and pushing back against the Trump administration, its policies, I and many other people who had been studying it, were saying that we were amazed at how long the movement had stayed mobilized, and yet peaceful. And they continue to push very specifically towards electoral change, right, most of the groups that were leading were all about the election, they were not about taking the streets, and encampments, and general strikes, etc, and so forth. Well, the climate movement was part of that. And today, there is a growing radical flank in the climate movement that is particularly interested in shaking up the system by working outside of it. So they no longer want to work through, you know the institutions that are the targets, in many cases of activism, they want to work outside of it. And so we see more and more civil disobedience happening in the streets. Most of it in the climate movement is quite performative and completely nonviolent. So that, you know, that’s something that I hope will continue, the groups that I study, and the groups that I continue to monitor, after the book has been published, have all continued to be extremely nonviolent focused. However, many of them have been starting to be faced with repression from either law enforcement security forces, or in some cases, we’re starting to see counter movements rise up to push back against in terms of being violent, which certainly and we also saw that, you know, this week with the violence on college campuses, which is not about climate change, so that mean that standard, right, you see people engaging in more and more civil disobedience, and then you see repression coming from the state, and you see counter movements coming out.

John Torpey

So I’m not sure I follow, counter-movements against climate change activists?

Dana Fisher

Counter movements against activists, right. So a perfect example of this, if you think back to the civil rights movement, counter protesters push back against peaceful, you know, mostly young black people who were sitting in and engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience. We call those counter protesters, white supremacist back then, because that’s what they were right? today. We are seeing folks who are starting to mobilize against climate activists, and starting to talk about the ways that they might bring the bring violence to the activists and target them. And it’s, it’s quite terrifying. But it is also very common when we see movements continue on and become radicalized, even though the radicalization of the climate movement itself is nonviolent. I mean, we see better examples of this happening in the UK and other parts of Europe, where there have been groups that have been, you know, mobilizing to beat up people who are blocking traffic or to be, you know, violent towards them. So you have somebody peaceful, you know, one of the big tactics you see in Europe is they do the slow marching, where they basically get in the middle of the road, a group of them wearing orange vests and just walk really slowly block traffic, pisses a lot of people off where there are some people who decided to organize and, you know, manually remove very forcefully these activists, we’re seeing stuff like that, and we’ll see more of it. I mean, we saw also some of that happening during, you know, the protests after George Floyd was murdered, right, where we saw Kyle Rittenhouse come out with his gun and, you know, was able to shoot activists and basically claim that he was part of a movement to protect his community. Right. That was a counter protest.

John Torpey

Yeah, I mean, I get that that was a counter protest. But there’s sort of specific people involved that you can counter protest against whereas climate change is, is a phenomenon that isn’t attached really to specific people in quite the same way. I mean, I okay. I can see how if people are slow walking in front of cars that are now being held up in traffic that those people might get mad. But that’s not likely to be a group of people who are going to come out and attack the people doing the slow walk.

Dana Fisher

Oh, that’s that’s absolutely not true. I mean, there’s lots of evidence of that. But if we see, we have seen numerous growing efforts by the radical flank of the climate movement, to occupy places to block banks, to glue themselves to things, to stop sporting events and the responses to that are getting increasingly threatening. And there are many people who are talking about starting to beat up the people who are doing that. And they have not, you know, really unified in a way, but one of the great examples of successful counter protests or counter movements, it’s just in your state this year, if we look at the push against wind power in the state of New Jersey, that was organized by a counter protest grant that was connected with fossil fuel interests, that funded the groups that were leading it, but nonetheless, that’s a counter movement.

John Torpey

Okay, I’m not saying there aren’t counter movements. I’m just saying that I wasn’t aware that there were that there were organized groups attacking climate activists. I mean, that’s kind of news to me, and worrisome obviously.

Dana Fisher

Well, no, they’re serious. They’re threatening, and there have not been attacks in the United States yet. But there are threats of that. But my argument is not that that’s happening now. My argument is that that is what will happen next, as we see more repression, and we see more disruption.

John Torpey

I see. Got it. Well, to understand these things better is the reason we do these interviews. So I want to thank you very much for coming on today. That’s it. For today’s episode. I want to thank Dana Fisher for sharing her insights about the climate crisis and how we’re going to address it. I want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance and to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song International Horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying, thanks for joining us. We look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.