The Everyday life behind Berlin Wall

In this episode of International Horizons, RBI director John Torpey interviews historian and journalist Katja Hoyer about her book Beyond the Wall: A History of East Germany (Basic Books, 2023). The conversation begins with a discussion of the personal reasons that the author, herself born in the GDR, wanted to cover the untold stories of her native country – which can no longer be found on a map. Hoyer also discusses the rationale behind the relative gender parity that existed in the GDR as compared with West Germany and how the legacy of that gender policy is reflected in today’s unified Germany. Hoyer also comments on the controversial reception of the book in Germany and concludes by discussing the ways in which those originally born in East Germany continue to suffer discrimination in social and organizational life in contemporary Germany.

Below, a slightly edited transcript:

John Torpey

There once was a country named the German Democratic Republic, the GDR or less formally East Germany. After the fall of the Berlin Wall almost 35 years ago, the GDR was absorbed into the larger and wealthier Federal Republic of Germany. The territory of the former GDR is often seen today mainly as a kind of bastion of far right and, to some extent, far left voters. While the experience of 40 years of communist society is largely forgotten, and contrary to Willy Brandt, West German Chancellor, Willy Brandt’s famous dictum that that which belongs together will now grow together when the Berlin Wall fell. It’s not clear that that’s actually played itself out what was life like in the GDR and what became of it.

John Torpey

My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche institute that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues.

John Torpey

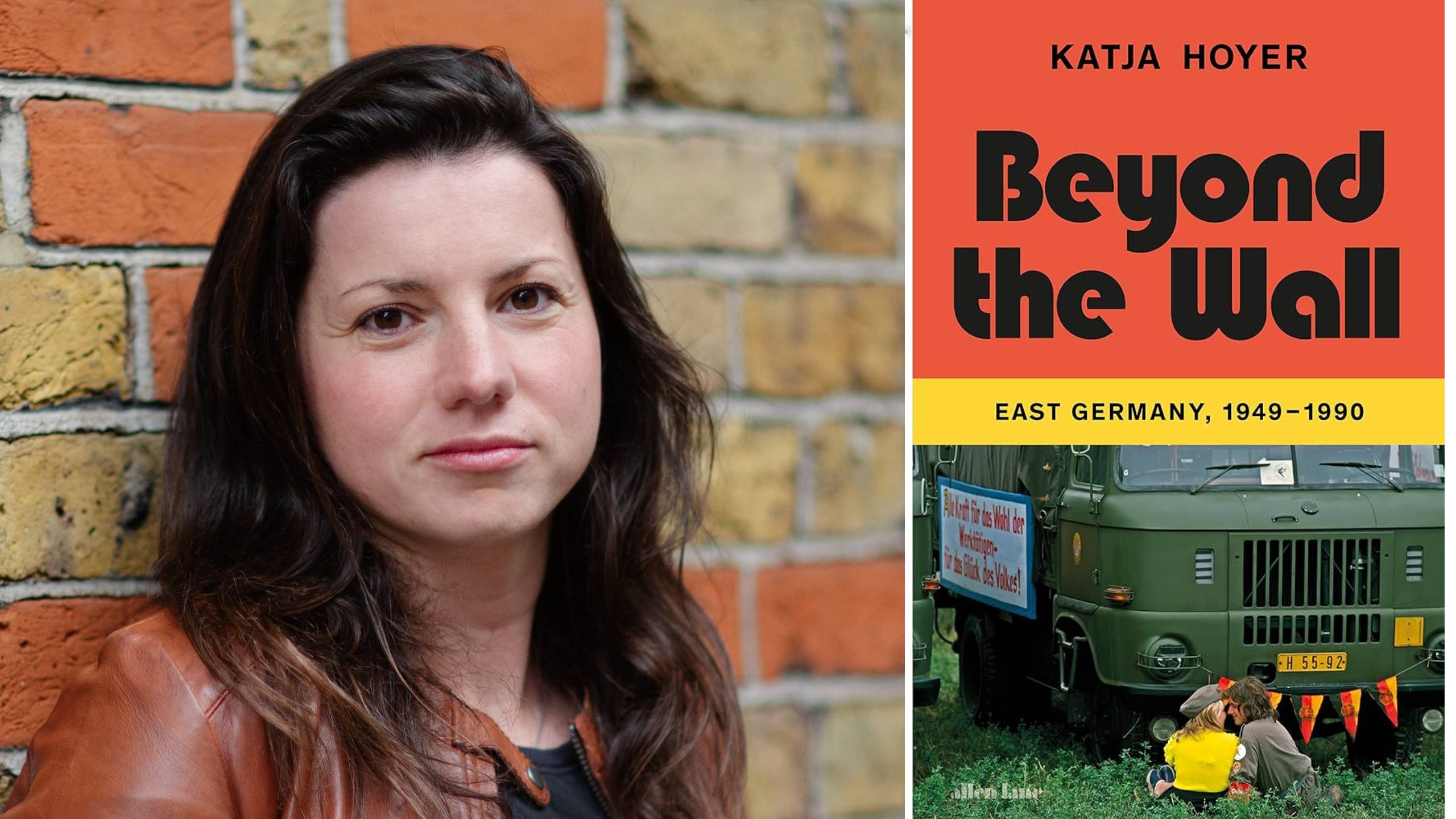

This one’s particularly close to my heart because it was the subject of my doctoral dissertation and first book and we’re very fortunate to have with us today, Katja Hoyer, historian and journalist born in the GDR, but now based in the UK. She’s most recently the author of the book Beyond the Wall: A History of East Germany, published by Basic Books . And she previously wrote the widely acclaimed Blood and Iron: The Rise and Fall of the German Empire, 1871-1918. She’s a visiting research fellow at King’s College London, a columnist at the Washington Post, and a fellow of the UK, Royal Historical Society. Thanks so much for joining us today, Katka Hoyer.

Katja Hoyer

Thank you for having me. Great to be here.

John Torpey

Great to have you. So I mean, the first thing that I thought about when I heard about this book was you know why now? What led you to write a history of East Germany? At this particular moment? Is there something that something going on in the world that prompted you to want to write following a book of this more historical, I suppose, about the German Empire that prompted you to write beyond the wall?

Katja Hoyer

Yeah. So, there’s several reasons really, one is that I think over 30 years have now passed between the fall of the Berlin Wall and now. And I was kind of hoping that being a generation on now from that, and having a whole generation of people, such as myself, who haven’t really got kind of a vested direct interest in that history, from, from a personal point of view, who haven’t themselves kind of lived through it. And what helped bring a bit of distance and a bit of clarity, maybe to the debate, because I think so far, it’s been dominated by people East and West Germans, who kind of directly grew up in this Cold War context, and are therefore shaped by it by themselves. So that was one of the reasons. Another one is that as you mentioned, at the beginning, was born in the GDR, but I was still a small child, when the Berlin Wall fell. So I was born in 1985. And therefore, only five years old when the country disappeared, and when was sort of reunited with West Germany. And so for me, there was always a degree of sort of personal curiosity there what was the state like that I was born into, that doesn’t exist anymore. I mean, that even goes for the city I was born and it was Wilhelm Pieck school named after the first and only president of the GDR. And so neither the city nor the country that I was born in, you can find today on a map and that curiosity was there as well.

Katja Hoyer

And then thirdly, myself and several other East Germans, most of them I think, feel a little bit aggrieved, just maybe too strong a word. But there’s a sense that that history is sidelined, not forgotten as such, but it’s kind of a footnote or the side story to the continuity story that is West Germany, and I wanted to change that. I think it is a chapter of the German story that’s important to tell in its own right. And that was what I was trying to do as well without constantly comparing it to the to the west.

John Torpey

So interestingly, I mean, there’s a quotation in the book that suggests that the GDR in a certain sense, it was not just a German state that it actually was born in a certain sense in Moscow in the 1920s. And I’m talking about a quotation of a guy named Wolfgang Leonhard, who came to the United States and taught Yale, I wrote a book about–I’m not sure that this ever actually translated into English–about his experiences as a young communist functionary who kind of ended up for incidental reasons growing up in Moscow, in the USSR as a young person. But he basically says something about a school that had been created for exiled German communists that their kids went to, Karl Liebknecht, and he said something about the history of the GDR began at this Karl Liebknecht school; Karl Liebknecht being, of course, a major figure in the early origins of German communism. So, I wonder, what did that mean? And in what sense might that be true?

Katja Hoyer

Well, I picked that quote up, because I think there’s some truth to it and people often forget that the people who founded the East German state in in 1949 didn’t come out of nowhere, they didn’t come out of the vacuum, they all have backstories, they all have experiences that shaped them, basically, that their previous lives are important. So I start the story a bit earlier, and look at communism and socialism in Germany, as an ideas and as an ideology well before East Germany ever came into existence, because I think it’s important to understand, with Marx, having been a German as well, and basically preached the fact that there would be a world revolution, and certainly, kind of a revolution within Germany very soon. And that hadn’t materialized in the 1920s. And in the 1930s, despite the calamity of the First World War. And so many of these kinds of German communists were still dreaming about communism, socialism, as they were battling the Nazis and nationalist people on the streets of of Germany in the 1920s. And it still wasn’t coming about, but there was a realization or third dream on earth at that point and that’s the Soviet Union, which became a communist state in 1917 and the in the October Revolution.

Katja Hoyer

So when when the Nazis come into power, and Hitler becomes the German chancellor in 1933, a lot of them kind of feel that they can kill two birds with one stone here, by going to the Soviet Union, there’ll be saved from Hitler. And they also get a chance to build up the first actual communist state that existed at the time. And Wolfgang Leonhard is one such example. He’s a young boy at the time, a teenager and his mother is a communist. And she takes him to Moscow and basically wants to raise them over there safe from the Nazis, but also in an environment where he can be schooled in the ideology of communism, and that applies to many others. And I think why that’s so significant is because the those communists didn’t find the socialist utopia that they were hoping for in the Soviet Union, but actually the opposite of deeply paranoid system under Stalin, which suspects all Germans that come to the Soviet Union, even though the most the vast majority of them are, of course, ideologically aligned with the system of being sort of fifth columnists for Hitler, people who will spy for Hitler and and feed information back. And so they get very severely cracked down upon by the time that style and basically rolls out as purchase in the mid and late 1930s. And the Politburo, for example, of the Communist Party, the leadership, nine of them go to the Soviet Union, and only two of them are still alive at the end of the war. And that’s Walter Ulbricht and Wilhelm Pieck, the to sort of early leaders of the GDR. And that in itself, I think, is so significant. I mean, these people have gone through an experience of prosecution of constantly looking over their shoulders, of having betrayed their own comrades. To save their own lives, basically, they said that other people were spies, even though they weren’t, literally delivering them to their deaths. They will never trust anybody again, and I think that’s hugely important when they come back to Germany. And they get sent back by Stalin to build up the Soviet Zone of Occupation. They don’t trust the population either or each other, for that matter. And so that the paranoia never goes away, and I think that’s important to understand if one wants to understand why it becomes. What it is, there’s almost this idea that kind of, there’s just a group of evil dictators to come back and for the sake of it, build a system that makes everybody miserable. And I think it’s important to understand why they never let go of that idea that everybody’s potentially an enemy, because that was their life experience up until 1949.

John Torpey

Yes, well, for my own dissertation research, I did an interview with Werner Eberlein, who had been as you know, basically the leading Russian translator because he also kind of grew up in this communist exiled German communist enclave in Moscow, and when I had the chance to interview him, he had just been a party secretary sort of, dragged in, he said, by Eric Honaker, just before the wall fell. But, he had a stroke when the wall fell, and the world that he knew had simply collapsed. I mean, he had only known in a way a world divided between communists and fascists. And I think, I’m not a doctor, I don’t know this, but I sort of had this sense when talking to him that, he just couldn’t kind of make sense of the world in the city. And it was quite striking, as an interviewer for somebody like me, who came from the United States, and for whom this was all a little bit distant reality.

John Torpey

But in any case, I mean, I wanted to get back to the issues about East Germany, some of which you just raised, this sense of paranoia, the Statsi state etc. I mean, this is kind of overwhelmingly the way the GDR is perceived, I think, by people that don’t necessarily spend a lot of time thinking about it. And, you explain this situation in some detail in the book is very interesting. I mean, I hadn’t really, ever thought about exactly the way they perceive the world, as full of threatening of people in a way. But you also have positive things to say about the GDR. And I mean, one of the things that struck me and that many people, I guess, observers have commented on is its gender ideology, to use a phrase that I probably shouldn’t use right now because it’s misleading. But, you know, the idea that Socialists were actually very committed to gender equality, and that it was not merely the fact that the GDR was in desperate need of labor power. And that’s why they created all these childcare stations, and, ways in which it would be easier for women to work. So maybe you could talk about that issue a little bit.

Katja Hoyer

Yeah, I think that’s a good point that you just made about this idea that it was done for labor reasons. So the idea that women were just used, as basically, a kind of resorts for the lack of cheap labor from foreign countries. So where Britain, for instance, had people coming from the Caribbean, and so on to to help rebuild it’s buildings that had been destroyed you and the war, West Germany invited people from Turkey and Italy, in East Germany couldn’t do that with its isolated economy. So one argument runs that women will kind of use to make up for that shortage of labor after the war. And that’s certainly part of it, but I think it is also a genuine part of the socialist ideology. And I think the reason why that’s been sidelines a little bit is because the moment you open up that debate, you invite comparison with the West German system, and with the German system today, and people will make demands along the lines of more childcare and enabling basically women to have families and the career at the same time. And so, it’s easier to say, well, they only did it for cynical reasons, and kind of brushed that aside. But I think that is just historically not true. I mean, when you look back at kind of where, for instance, International Women’s Day, and those sorts of things come from, they’re deeply intertwined with socialist movements in the First World War and beforehand as well, because it is part of the ideology. And one example I use in the book to show that is a party communiqué that was published in the party newspaper Neues Deutschland, where the ruling party basically rants about the way that women are treated in the workplace as kind of a long, very modern sounding argument that men aren’t treating their female colleagues seriously enough, there’s still an argument that women haven’t got a head for the hard sciences or for economics. Men don’t understand that women have a kind of double task then and trying to do their jobs and look after the household and kind of be wives and mothers as well. And all of that all sounds very modern. I mean, you could print that if you take words out of there, basically the register, you’d end up with a very modern piece you could print in the newspaper today, and people would sign that off and say, “Yeah, that’s exactly the problems.” And that doesn’t sound to me, like women were kind of just chained to the factory floor because they needed cheap workers. And it became sort of more normal as well for women as time went on that they kind of just expect to be workers and nothing that’s like this cultural change that they achieved, hasn’t gone away. You still see differences today in eastern West Germany, between kind of female labor. For example, the gender pay gap isn’t not only not existent in East Germany, it’s actually reversed; women earn slightly more in East Germany than their male counterparts. The gender pay gap exists in West Germany as it does in most western societies. And that’s simply because women kind of don’t go part time, you know, they follow their careers, they find out very important, and they manage together with childcare, basically to stay in their jobs and not take long breaks from them, which is just a cultural thing, that’s become normalized for them.

Katja Hoyer

Right. Interesting. So, I mean, I guess this gets us in a way into the question of the way the book’s been received more generally. You know, you’ve mentioned now the kind of controversy over the status of women in Easte and West during the Cold War and after, but I gather, there’s a sort of bifurcated reception, or at least, it seems that there’s a sort of more positive reception in what we might call the Anglosphere, and that the book is more controversial in Germany. I haven’t had a chance to sort of confirm that independently, but a historian, friend of mine who pays attention to such things tells me that’s the case. So I’m curious, what you would say is going on? I mean, is that an accurate assessment of the reception in the first instance? And then, if so, you know, what’s going on?

Katja Hoyer

Yeah, it was really interesting to watch for me as well, because, so I wrote the book in English. And it came out in the UK first, where it was received, worked very well across the political spectrum. So I was quite relieved to see that because I genuinely intended to write a book that doesn’t judge politically, but kind of just explains and analyzes the history as such. And so it was interesting to see that from the sort of conservative press all the way to the to the far left outlets, it had been received very positively. And in Germany, it has had a very mixed and very acrimonious, I’d say, response, both positive and negative. And I think that’s largely due to the fact that it’s Germany’s history, it’s kind of something that’s very raw, still very emotional. I’m talking about people’s own backgrounds here still, especially people who are older than me, and will basically say, “Well, I was there, I know what it was like.” It doesn’t take much one paragraph often, for somebody to say, “you know, I would have described it differently. And why did you do it that way.” And because those people’s own backgrounds, people’s own history, there is that raw emotionality about it.

Katja Hoyer

I think the other thing is that for a long time, Germany has done a GDR history and still does actually through a state funded organization called the Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung, which is like a federal agency whose task it is to look after the history of the GDR and go through it. But when you look at its founding statute, it basically says its purpose is to preserve the history of the victims of the GDR. So it’s a very, there’s a very specific aim to the way that that GDR history is written in Germany, it’s kind of like a pedagogical tool that we use to train young people to date become democratic liberal citizens. And in that way, the GDR and Nazi Germany are used in tandem, to show kind of what dictatorships look like the GDR is often actually called the second dictatorship, meaning the second after Nazism in Germany. And because they know that’s the organization where the funding comes from, where the appointments for things come from, it’s a very specific thing that they’re looking for. And that isn’t what I did kind of sitting outside looking at the GDR with a different eye, with a more… I would say, with a broader look to telling the mainstream story. I’ve got the victims in there, but because the victims are, on the whole, the people who were directly say, targeted by the Statsi, or were being shot at the Berlin Wall, they’re all in my book, but they’re in proportion to the proportion that they, in my view, took in society, and that’s the minority. And that’s also been a point where people are deeply unhappy with art because they see the history of the victims as the history that should come out of this not the history of the majority that kind of lived their lives in the GDR, and was seen as complicit in, in the system. And because I sort of turned that on its head and tell the story of the mainstream alongside the story of the victims, but they become one part and not the only part basically, I think that’s also led to a lot of controversy. But I should say that normal readers in inverted commas, kind of, the mass of people read the book, tend to be very positive about us got very good reviews on Amazon, even in Germany as well. I get letters from Eastern West German saying that this is the first time they’ve actually engaged with GDR history because they don’t feel the constant finger wagging is basically putting a spanner in the works. And overall, I would say that, this kind of idea that it’s negatively received comes from the reviewers who themselves are part of this organization that I just described, more affiliated with it.

John Torpey

I see. So just to clarify, for those who may not speak German, she’s talking about a Federal Institute for coming to terms with the past, the Bundesanstalt fuer Vergangenheitsbewaeltigung. I’m not sure what the exact title is, but something along those lines, Germany is a place where there’s a lot of coming to terms with the past. And, you know, this is part of that operation. I guess I’m curious, leaving aside in a way, the history, there’s this famous quotation of Willy Brandt, that I mentioned in the introduction about now that which, belongs together, we’ll grow together. And I guess, Wolf Lepenies is a very prominent intellectual said something about, this would take a generation. I mean, how do you think that process is working out? Or has worked out? And, what would you say about how successful it’s been?

Katja Hoyer

I think, on the whole, a lot of money was invested, lots of infrastructure was being built, literally billions were invested in things like roads and making East Germany look like West Germany. So now driving back and forth, obviously, you recognize a difference in architecture, but the standard of things is improved. And so we have people’s living standard. So most of the the vectors that you can look at for, you know, kind of economic parity, have actually closed down so that there’s less difference there between East and West. What hasn’t really changed, though, is a fundamental lack of participation of the of the East. So there’s another book that recently came out which contributed to this controversy I just talked about around my book as well, they kind of were seen as one package, if you will. And that was about the period after 1990. And some of the figures in it are just shocking, really, you’ve got, for instance, in terms of participation in elite positions in society. So in politics and across economics, about 1.4% of leadership positions are occupied by East Germans when they actually make up a fifth of the population. And so that, I think is a problem because you then get very stereotypical depictions of East Germans in the press, or in films or in the media, basically, where people feel that they’re not taken seriously. They’re not part of the discussion. Even when I’m sometimes invited to talks and on panels and things quite often the suggested sort of headlines for these talks are things like, “why is the East still different?” Or, you know, “what’s the East like?” you know, there’s always kind of this idea of you looking at on from the West as the point of normalcy, and you’re trying to work out whether East doesn’t quite fit in with that. And I think that’s an image that has kind of stuck with many East Germans and why there’s so much acrimony there. And I think the other issue, as well as that, when you said earlier about the idea of East Germany as a land of sort of far right extremism and far left extremism to some extent, and that that’s often been treated as a natural outcome of a people that lived under a dictatorship and was socialized in a dictatorship, which I think makes a complete nonsense of the whole thing. I mean, when if you apply that, you effectively end up writing these people off, because you’re saying they’re just like that they were just kind of raised like that. And so there’s no point trying to convince them otherwise. And that in itself, the sort of arrogance and the writing off that people see in the media and from politicians, has also been deeply unhelpful. There was for instance, the head of one of the largest media operations in Germany of the Alex Springer press, was there were leaks, basically, where he said that “all these Germans are either fascists or communists, and he’s disgusted by that.” When you have somebody at the head of a huge newspaper, and media kind of concern, thinking like that, it seeps down into the way that articles are written into the way that East Germany is portrayed. So I think in terms of growing together, I think economically and otherwise, that is sort of happening, but East Germans still feel in lots of ways that they are being excluded or seen as kind of the lesser Germans, not real Germans. I actually spoke with Angela Merkel is arguably the most famous East German, complaining in her last speech in office as German Chancellor that even she, her own biography is basically constantly being reduced to kind of stuff that happened after 1990, and even she feels that she can’t talk about her past despite being arguably the most successful East German post wall story if you will. Even she doesn’t feel that she fully kind of arrived and was taken seriously despite being Chancellor.

John Torpey

Interesting. I mean, as you talk about this, I guess I wonder, do people see this that is to say, the under representation of East Germans in leading positions in the society? Do people see that as a problem that needs to be addressed and that can be addressed in some ways? I mean, given some of the debates we’ve had in the United States recently, I wonder about kind of an affirmative action program, I mean, exactly who the beneficiaries would be is not entirely clear, as it is not really in the case of the United States, but it does strike me that in a way this population is treated as, or is de facto in a situation in a position that is the product in a way of kind of historical discrimination. And I just wonder, is there a discussion about doing something about this? Does it sound anything like our affirmative action debates?

Katja Hoyer

I think that is a debate this year, that’s partially due to the fact that this other book I was just talking about by a guy called Dirk Oschmann, and mine have created a massive public discourse about this, in the light of these political problems that we just talked about, because there are elections in three of the East German states next year, and people are very worried that the far right Alternative for Germany (AFD) will win in those states. And as a result of that, mainstream politicians are increasingly worried. And so I, for instance, get a lot of emails these days from politicians, or their aides kind of saying, you know, “can they talk to me about this?” And is there a way out of this, and I don’t know how much help I am with that. But at least there’s now a desire to work out what’s actually going on and what the problem is. And I think previously, there hasn’t been much understanding for that simply because East Germans are only a fifth of the population, they weren’t previously seen, as kind of necessary to win elections, and therefore, to smaller group to kind of worry about, and some people have tried to make a case in court about discrimination. So, for instance, there was a, I think, a woman a few years ago, who was actually sacked from her job with kind of an insight along the lines of, you’re just a stupid Aussie, or something along those lines in East German, and she kind of tried to make a case that she was being discriminated upon, because of her being East German, in the same way that you would be able to do if it was based on her gender, or ethnicity or religion. And the courts shot that down. And there were three other cases like that. And again, the kind of ruling was upheld, that you cannot be that basically being determined doesn’t count as being a minority, and therefore, you can’t claim that you’re being discriminated. So your boss has got every right basically, to turn around and sack you and say, “I don’t want any East Germans working here, which has apparently happened.”

Katja Hoyer

So I think, you know, there’s, it’s a slow change that’s happening now, because of the political circumstances. And it remains to be seen whether that will last and how long it will last, but certain debates do include, kind of the idea of having a quota of how many East Germans you would have or things like that, which I’m not entirely sure that that would be helpful, because I think it’s more of a symptom than the cause, I think the idea that, you could suddenly say, “Okay, let’s have, like three East Germans in each government department or whatever,” I don’t think that would necessarily solve the problem kind of that lies behind that.

John Torpey

So it wouldn’t solve the problem, or it would generate a backlash in the process.

Katja Hoyer

Probably. I mean, people would also feel a lot of people feel that they just do not want to be labeled as East Germans, like the guy whom with we’ve written that other book Dirk Oschmann said that, he comes from the East side, he’s a German. So you know, either of those two apply to him, but he doesn’t see himself as an East German as such. And therefore doesn’t want to be labeled with that either. So that’s not really the sort of right way to stick a label on people and say, “you know, you should be in this position because your East German” is more way of measuring whether that kind of society, the process of growing the society back together, has worked. So I think it would create a backlash as well as being not particularly helpful because it doesn’t solve the issue itself. I mean, the fundamentally the issue is that the GDR created a society that was supposed to be classless, so it basically got rid off of the middle classes, both culturally and economically. And you see that in all sorts of you know, economic factors like people inherit less from their parents, they got less financial stability. Therefore, for instance, they’re less able to save for instance, go to university or pursue a PhD afterwards because they’re just economically in a precarious position and can’t do that. They didn’t have the mannerisms to impress somebody at a job interview in the same way that somebody who comes from a different background would do. So it’s just an overall issue that I think there needs to be a more complex solution to.

John Torpey

Very interesting. Well, it’s really been great to have a chance to talk to you. That’s it for today’s episode of International Horizons. I want to thank Katya Hoyer for giving us the opportunity to hear more about her recent book Beyond the Wall history of East Germany and to hear about the controversy that is generated. I also want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance and to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for letting us use his song International Horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.