Resentment: The complexity of an emotion and its effect on politics

In this episode of International Horizons, RBI director John Torpey interviews Rob Schneider, Professor of History at Indiana University-Bloomington, about the political effects of resentment. Schneider begins by discussing the psychological complexity of resentment and then delves into its understanding by other authors such as Nietzsche and its relationship with Catholicism. Moving forward, Schneider discusses how resentment is related to identity politics and how some sectors of the population have been neglected on the basis of the claim that they are privileged. Finally, he elaborates on the making of forgiveness in divided societies and how it is often imposed on some who are not yet ready to forgive.

John Torpey 00:02

As has been widely noted, “resentment” has been very much in vogue as an idea for understanding the roots of contemporary populist rage in the United States, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. Yet not so long ago, this sort of analysis of extremist politics was not regarded as polite among historians. Former President Barack Obama was excoriated for invoking an analysis of what was happening on the American right. What can we say about the role resentment plays in contemporary politics?

John Torpey 00:38

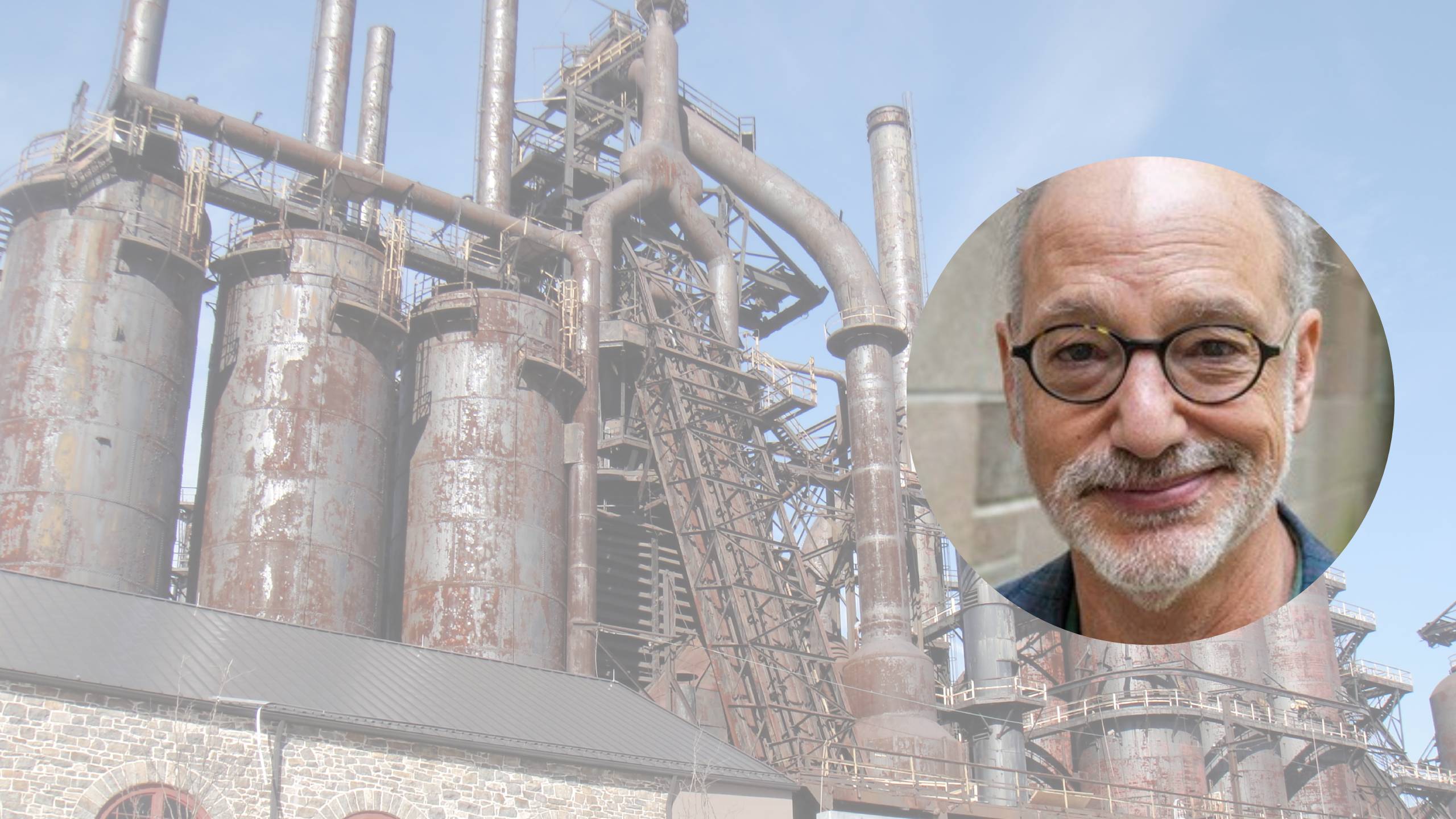

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. We are fortunate to have with us today Rob Schneider, who is Professor of History at Indiana University-Bloomington. He is the author of three books and many articles on Early Modern France and, most recently, of The Return of Resentment: The Rise and Decline and Rise Again of a Political Emotion (University of Chicago Press, 2023). From 2005 to 2015, he was editor of the American Historical Review, the flagship journal of the American Historical Association. He has been a Visiting Fellow at All Souls College and Oriel College at Oxford University, and a visiting lecturer in residence on three occasions at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris. He has received fellowships from the Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the French Government (Bourse Chateaubriand). During the current academic year, he is Visiting Scholar in the Department of History at the University of Pennsylvania. Thanks for joining us today, Rob Schneider.

Rob Schneider 02:17

It’s my pleasure to be here.

John Torpey 02:19

Great to have you. So you start this book by noting that resentment is a complex emotional phenomenon. It’s related to anger and indignation, but it’s not the same as either. So maybe you could start by explaining, you know, what you think resentment is? And why you decided to devote a whole book to addressing its significance?

Rob Schneider 02:42

Well, let me address the second part. First, you know, the fact is that I had been observing over the period of at least 2016. The, though, the appearance of resentment in op-ed pieces in headlines is as a term, which seem to be used as what I would say a kind of off the shelf explanation for the phenomenon of the new right of Trump, about the sorts of phenomena that really are, quite, quite frankly, disturbing to many people and, and puzzling. And it seemed to me that resentment was used as like something you would just throw at this and say, “oh, yeah, that’s what they do. That’s what they are. That’s what explains this. They’re just resentful.” But it seems to me, and I think this is true for most people, think about this resentment, and this it gets to your the first part of the question.

Rob Schneider 03:38

Resentment is a complex emotion. All emotions are complex. And accessing emotions, of course, is a very difficult task. But I think most people would agree and certainly, most moral philosophers and psychologists would agree, that emotions are never just feeling; is a mix of thinking and feeling when it comes to emotion. So already, you’re dealing with something complex with resentment, as opposed to say, fear or hope, or anger. I think we’re dealing with an emotion that, if you wish, has unbalanced a little bit more thinking or psychological reflection than just feeling. Indeed, the word itself in bytes of the assumption that it’s returning to something.

Rob Schneider 04:21

So it’s not just a matter of feeling, thinking something at the moment, but it’s a matter also of cultivating or thinking or mulling over a sort of reaction to things. So the first resentment is particularly complex and therefore deploying it the way it has been used, rather unthinkingly or casually I think invites interrogation. What do we mean by emotion by this emotion by resentment? I think to resent involves not just a sort of sense of being injured but a moral injury. And I think the rather trivial knowledge we have, say, having someone step on your toe, and apologizing, well, your toe is hurt, but you you accept the apology. If someone, say, then steps on your toe the physical pain, and then fails to apologize, the physical pain is the same. But it’s been compounded by a kind of moral outrage, that something has been violated a certain protocol certain requirement that one apologized for an action that is hurtful. And it seems to me that resentment has this component to it. It’s not just a kind of injury. It’s an injury which has been molded over and which is complexified by a sense of moral outrage. And therefore, I think resentment also then represents a sort of violation of expectations, that we have certain assumptions, a certain set of, of expectations of principles that should not be violated, that should be followed. And that when these are violated, it’s not just a matter of something happening, which is harmful, it’s a matter of, again, a moral injury. And here, I think the analogy which I use in the book, which other people have also used is, again, a rather trivial one, but it can expand be expanded to the collective experience is jumping the queue or breaking in line.

Rob Schneider 04:35

That is to say, all of us, I think, if we’re standing in line for something, we expect that people are going to stand in line and keep to the protocol of one person after another. If someone jumps the queue, that’s a violation of a principle of an expectation. And I think this can be seen on were magnified level by those people who feel as though others have jumped the queue. And again, it’s not a matter of endorsing the legitimacy of this, but it’s a matter of this is what people think the immigrants or women or different ethnic groups have been promoted by the governments say, and given preferential treatment over those who are sort of waiting in line. So I think this is this sort of captures that sense of, of moral outrage.

Rob Schneider 07:06

Finally, I think there’s the question of time. Resentment, as I suggested before, implies a sense of returning to something, this soul tear. And there, I think, unlike many emotions, it often dwells on the harm on the outrage on the violation. And, therefore, this sense of time is very, very important for, I think, the experience of the emotion, especially on a collective level.

John Torpey 07:42

Great. So very interesting sort of explication. But I think most people and perhaps, including me, when I first received your book, think perhaps about Friedrich Nietzsche, his analysis of resentment, I mean, he built a whole theory of the modern world or theory of Christianity. I mean, it was huge at the book always had a huge impact on me, partially because, like a lot of the things he says, It’s so outrageous, or it seems so outrageous to kind of make this this argument about a slave revolt in morals. But you are not, I think, particularly happy with, Nietzsche, his use of the term. So I wonder, since that’s probably the most familiar thing to most people, can talk about that a little bit.

Rob Schneider 08:35

Yes. Well, this certainly, I mean, any discussion of Nietzsche of resentment. Nietzsche looms large, you just can’t get around it. And I think this is for good, and not so good reasons. In some ways. It prejudices, our sense of what this means insofar as he’s cast it as an entirely negative emotion with psychological disposition that it is merely that which inculcates in the masses in the earth, the slave morality, which is a betrayal of the principles of the values that he holds up as being those that we certain individuals or extraordinary should follow. That is the idea of strength and heroism and beauty. Individualism in the slave morality of those who are resentful is the opposite in every respect. So Nietzsche’s book, and largely The Genealogy of Morality, from 1887 had determined its [resentment’s] influence. And in some sense, it pushes us in the direction of seeing it as entirely negative.

Rob Schneider 09:37

I should add, and I should have maybe mentioned this earlier, one of the kinds of problems with resentment as an emotion is that most people might want to qualify this by saying most people sort of are not happy to own resentment. It immediately puts yourself in a sense of being a victim. And no one really wants to, I think, embrace a victimhood voluntarily so it’s got that sort of negative cat As much of course, Nietzsche both channeled and expounded and made so determinant in some, in some ways in terms of how we think of it. But Nietzsche’s fashion resentment has this as the morality of the slaves.

Rob Schneider 10:15

Now, interestingly, in the book, it really unfolds in several steps. I mean, you have the slaves who are, of course, in a situation of being oppressed, and the nobles are their oppressors oppressors. But the normals don’t have a bad conscience about it. And that’s one of the things that he really likes about nobles. They’re not conflicted about at all, and there’s no sense of guilt, there’s no sense of self consciousness, they’re happy to embrace the position which after all, they deserve, they are these Homeric thinkers who are above it all. The slaves, on the other hand grown under their oppression, but they don’t do anything about it. You know, as Nietzsche is concerned, historically, let’s be clear, this is not an historical account. It’s a myth, a very powerful myth. So they grown under their oppression, they feel resentful, and they can sue in that. Now, the second part of Nietzsche’s analysis, which is often left out is that what is needed to promote and develop what he eventually calls resentment as a slave morality. What is needed is the priests, they come in, and who are the priests that are Jewish priests? Say they’re the early Christians, it’s again, historically very imprecise, but that doesn’t matter to Nietzsche.

Rob Schneider 11:32

So along comes the priests and they sort of tell the masses, “you are the oppressed, you are the sufferers, but you will be rewarded elsewhere in heaven or whatever.” And moreover, your suffering, your weakness, your passivity, your all of those are virtues. And they lead to not the strength, not the power, not the beauty, but to forgiveness, to mercy, which indeed becomes, of course, Christian morality. So for Nietzsche, resentment, the slave morality, the oppression of the slaves, the priests, machinations on the earth, all of this yields a kind of a morality, which he says is really is that a Western, Judeo Christian civilization. To in his mind lamentable effects, because what we’ve done is we’ve betrayed something innately human, at least, as he would have us be aspirationally, which is not towards meekness and forgiveness and passivity, and the meek inheriting of the Earth, but rather [towards] strength, power, individualism, beauty, and other values, which he sees as being overturned by Christian morality. So it’s, it’s an inversion of values, and Nietzsche is the preacher who wants us to recover the values that have been inverted. It’s extremely powerful. And even those who never read Nietzsche, and I think, well, I mean, it’s one of these books, which I think still read my undergraduates, but even those who don’t read them, it’s that notion of being a negative emotion is still there implicitly, in the term.

John Torpey 13:13

Right. I mean, I’ve always been struck by how bracing, and I opening reading Nietzsche can be, I mean, as I say, I mean, to some degree, it’s so outrageous, the sort of argument that he’s making, but it clarifies the world we live in, in this incredibly blinding sort of way, it seems to me. And he’s, anyway…

Rob Schneider 13:37

it’s very seductive. It really is.

John Torpey 13:39

Is very seductive…

Rob Schneider 13:40

I think especially for a young person.

John Torpey 13:44

And, you know, I don’t want to drag Trump into this yet, I’m sure he’s going to get into this discussion. But, you know, there’s a way in which that morality that Nietzsche clearly prefers. You know, insofar as Donald Trump embraces really anything, you could sort of see him for siding with Nietzsche on this. Anyway, we’ll leave that aside, we’ll get to it. You know, in the book, you sort of make a distinction between two kind of versions of resentment. One is the kind of left behind and threatened worldview that is widely seen as the kind of base of the Trump support. And then you sort of say, well, but there’s also a much broader, I mean, let’s not blame it all on them or describe it all to them. There’s also a kind of way in which resentment is, you know, an intrinsic part of the modern world in a way that the modern world proclaims equality but fails to live up to that reality. And so that there’s a kind of resentment in all of us all the time. So I wonder if you could talk about, those two, shall we say, ideal types?

Rob Schneider 14:55

Right. I would say, rather, it’s not that necessarily resentment is in all of us. But that it is a potential collective emotion that characterize perhaps the modern world. And let me just be clear, I mean, this is a hypothesis in the book that I think I’ll stand by. That is to say resentment individually is perennial, that is to say it’s not historically specific as a collective emotion. And this is my interest in the book politically and collectively, the sense that the resentment is meaningful and important. It seems to me that in a sort of pre-modern world, before the 18th century, or before the early part of the 19th century, however you want to demark the modern world, resentment as a collective phenomenon really wasn’t something that we’re going to see, in part because a people could not presume that they had a claim to be equal to those who were above them. When you don’t have democracy, equality, at least in principle, then while peasants are suffering, and they’re angry, to get their feudal lords, they can’t be be resentful for them.

Rob Schneider 16:03

Because the Lords in a sense by right in terms of the ethos of the period, have real privilege, which are have privileges which are universally acknowledged. It’s only when you have the ethos or the expectation, at least the principles of equality democracy, when people as Tocqueville I think, brilliantly outlined that when there’s an aspiration and the expectation of equality that is not met, then you have resentment as a potential and least emotion, which can take hold among people individually, or more meaningfully here, for me, collectively. So I think there’s a kind of floor if you wish, that’s to say, resentment, collective feelings of resentment are part of the inventory of emotions that are part and parcel of the modern world, the way they weren’t in a pre modern world. So in that sense, yes, we’re all susceptible to, to resentment, and increasingly as people’s expectations are changing, and perhaps be finding being refined, it’s not just a recognition of me, say, as a citizen, equal to you as another citizen, but I begin to have people begin to say, No, you must recognize me and my particularity. That is I am of an ethnic group, or I have a certain sexual or gender orientation, are of a certain particular identity, which is which transcends, and to me is more profound than just the sort of citizenship that we all share, then you get a sense that, well, if that recognition is not coming, either legally or otherwise, from people, I’m going to reduce resentful, because that’s who I am.

Rob Schneider 17:44

And I have the expectation that you recognize me and my particularity. And that gets into the whole question, the vexed question of identity politics. I think identity politics, as people from both the right and the left have suggested is not only incredibly vexing, sometimes but also invites a kind of resentment as a dynamic, which ultimately, is very difficult to see being resolved. Now. There’s that and there’s a more general sense of resentment, when you talk about what I say called the threatened and the left behind, that’s when you get the sort of the sharp, so angry kind of resentment that we see part and parcel of say, the MAGA movement, that they are have certain expectations about being, say, white people, white men, and they see around them ways in which both the government and the culture are undermining that or are unfairly treating them are demoting them. That their whole sense of who they are in this world, who their parents were who their grandparents were, this is the world is changing in a way such that they are being devoted, or threatened. And there I think the resentment is really bad fears, an angry and threatening.

John Torpey 18:58

Right, well, this does get us into the complexities of identity politics, and you raise this in a particular point in the book, when somebody starts talking about white privilege, or white supremacy, one can at one level, understand that as an account of what American society looks like, but at the same time, there are white people whose experience in the recent past is nothing like; one of privilege or god knows supremacy. And so, you know, how much those people constitute the base of the megamovement? I’m not sure we can exactly say but it certainly seems to be a key part of understanding where this contemporary right wing populism in the U.S. and arguably in other places as well. You know, where it comes from?

Rob Schneider 19:54

Yeah, I mean I’m a historian and I’m not a pundit. And I speak as a historian who takes that historical set of experiences to bear on the present, because I am also a citizen, and a concerned one. But it seems to be the one of the things that I wrote the book in a sense for is to maybe prompt readers to be a little careful in how they look upon those who are very different in their thinking and their orientation, who are who are angry, and whose disposition is very easy to see it as being merely resentful and unjustly. And that is they have no reason to be resentful. And to sort of write them off. And whatever you think about their political posture, it seems that they are say calling, using the term “white privilege,” in a very casual, indiscriminate way, is just sort of pouring salt into into their wounds, because we do have a vast number of people in this country, who are white, who are working class who have been really abused by the forces of globalization and neoliberalism. Have you wanted to describe it the ways in which if you just traveled throughout this country, and you see towns that have been emptied by any meaningful industry or work, where a generation before there was a sense of a civic life and economic life, that the current job problems among those sorts of people, I mean, it’s just, it’s a kind of plague.

Rob Schneider 21:25

And to sort of say that, “Oh, they have there’s no basis to their grievance, they’re merely psychologically sort of twisted to see them as merely acting out symptoms” is to, I think, write them off. And I think those who have sort of liberal disposition, are often guilty of a cutting of an elitism, which is very condescending about them. That really, I mean, literally, it frames these people, it’s living in flyover country. And that very metaphor, a flyover, you’re looking down on these people who are after all citizens, and they vote, and they again, well, there’s this is complicated by the racism and the xenophobia and the sexism, which is often part of that culture or those people’s dispositions.

Rob Schneider 22:15

I think, we can draw a line between seeing them as being wrong, ideologically or politically. And yet understanding where they’re coming from and having some sort of sympathy of the forces which have impinged upon them in a very profound way. So I wrote this book in a sense, to help people to try to get people to think differently, and carefully about how we ascribe emotions to people who we most cases don’t even know; they’ve been represented to us through the media, often in very, very problematic ways.

Rob Schneider 22:50

But I think, you know, it’s a matter of people who are in this country, many of them feel as though they’ve given a raw deal. And as resentful, and this is, I think, part of what we see with resentment, they often see the wrong sorts of forces, the wrong sorts of people as the enemy, just as the Germans saw the Jews as being the conspirators who were doing the German nation and its its prospects. So people see immigrants or African Americans or women as being the enemy, whereas in fact, it’s other forces, I think, that are social and economic, up into their lives. And so I think we have to sort of understand what resentment often fosters in terms of a misdirection of what really is the source of difficulties here.

John Torpey 23:49

Right. I mean, I don’t know how much we want to get into this. But you know, to some extent, my own view of this is that this is probably partially a product of the fact that identity politics tends to be a kind of elite phenomenon. And the idea of class, which used to be part of this trinity of race, class, and gender, has largely disappeared. And so there’s no room, there’s no place in that image in that critique of the United States. For the guy in Akron, who’s factory packed up and went to Mexico or Korea or whatever, Brazil, whatever the place was, and you can now roll a bowling ball down the main street of Akron and not hear a thing. And so you know, there’s something a little bit short sighted and self regarding in effect of this way of thinking about the world, and I think we need to get beyond it.

Rob Schneider 24:54

I mean, again, it’s very difficult to parse these things, because I think as you point out, identity politics tends to be inward looking. And as people also pointed out, it doesn’t easily lead to a productive, poor form of politics, which joins up with other people who feel oppressed or left out. Nevertheless, identity is a fact. And identity politics and people’s identities as they have developed through the cultivation of rights, and the evolution of our culture, especially in the direction of sexuality and gender. And what that fosters in terms of identity. These are facts that have to be dealt with. I mean, we just can’t wish that people would not be invested in identity politics, it’s something that is got to be joined up in some meaningful way with a politics which is broader base. That’s, the trickier I don’t know what the instruments of that move would be. But it seems to me, we’ve got to get out of this impasse, we’ve got to do that. And you’re right, it tends to be elite, it tends to be university based or academic. And, of course, it’s therefore easy target for those who want to take advantage of and exploit it.

John Torpey 26:06

Right. So you also say in the book that or you suggest that the culture wars are kind of partially a generational conflict, and that there’s resentment among younger would be academics who are finding it difficult to, you know, get a foothold in the academic job market for reasons that have nothing to do with us hanging around, but that have to do with the decline in college level enrollments and the demographic reasons and lack of funding of public higher education by state legislatures. But you know, it’s true that we are kind of hanging around from the perspective of somebody who can’t get a job, we’re beyond ourselves by date, perhaps. So, I wonder if you could talk about how you see that?

Rob Schneider 27:02

Well, let me just back up and say, I think the generational conflict has a longer tail to it. And the sense that part of what people are still reacting to, that is those who feel threatened, mostly sort of white people, middle class and working class people, is the still manifesting results of the 60s and the cultural revolutions, which, in fact, has never ended; especially in terms of gender, representation, identity, and sexuality, and they see Hollywood as the purveyor of this, that that these sorts of cultural manifestations, threaten everything they hold, dear, that is the sacred sexuality of the family, gender roles that are tradition, community, church, the religion, all of these things which people find as meaningful in their lives, they see the cultural transformation from the 60s and everything that I think defines them in many ways, the, let’s say, our urban popular culture as being highly noxious to their way of being and that I think it’s a friction point, which breeds resentment. When you come to the further generational conflict, as you say, I think we’re dealing not only in terms of academia, but perhaps a whole, a whole generation beyond academia, of people might my daughter’s age, and they’re around 30 years old, who are educated, who are ambitious, but they find in terms of housing, in terms of positions and terms for many of them–fortunately, my daughters don’t have this problem, student debt–they got a raw deal and the expectation that they would match minimum surpass their parents level of economic wellbeing that this is now something that they no longer can count on. I think one of the things that least we celebrate as another myth that America is social mobility, social advancement, that we will do better than our parents and indeed, for the post war generation, I think, certainly my parents who grew up as children in the depression and benefited from the post war boom, they certainly did better than their parents who actually did really well even as immigrants. And yet now, I think the people who are younger, that notion goes up and down the social skill, that the sense of improvement of advancement of mobility has been undermined. And the prospects are very, very slim except for a narrowing elite. And even for them, I mean, people who become doctors and lawyers, I mean, if you talk to people who are going into those professions, now they’re largely corporate often in their organization, they have no control over what they do. Again to there’s a sense that their aspirations and expectations have been disappointed.

Rob Schneider 29:55

And I think this insofar as this is a broad based phenomenon. It doesn’t bode well for the sense of optimism of growth that we’ve always celebrated as being central to the American ethos, even though disappointment runs throughout our history. And indeed, as a part of existential life, let’s not get ourselves. So I think we’re dealing with effects moment. And disaffection clearly is something that is endemic.

John Torpey 30:25

Well, maybe this kind of brings us to a last question, which, was one of the things in the book that intrigued me. And that is the kind of, your observation of the sort of positive side of resentment of its productive side of its future orientation of its aspiration to do better than that which is resented. So maybe you could talk a little bit about that, as we close.

Rob Schneider 30:51

Yeah, that was the surprise for me, because I came into the book, the whole project, thinking about Trump and other aspects of resentment as a negative phenomena. And I just discovered that moral philosophers and others had, in fact been suggesting another way of looking at resentment, in a sense we could say it’s like James Scott’s have one of the “instruments of the weak.” I mean, what do people who are left behind or otherwise discarded or excluded or oppressed, what do they have, but they’re sort of anger. But here, it’s seen as a resentment, that is to say, don’t pass me by, don’t ignore me. Ignoring me, passing me by moving forward without addressing my grievances. This is something that we deeply resent.

Rob Schneider 31:40

And I think the emblematic figure to this and there are many, but the one who was most arresting in his writings is Jean Améry, who was a Holocaust survivor, a member of the resistance, he was tortured. He was imprisoned in Auschwitz. And he became a writer of some repute in Europe in the post war era. He left Germany, he lived in Belgium, but he observed Germany in the 60s, as really what he saw just moving on that people were just decided that what their fathers had done under the Nazi period that was done, and that’s over with, and now they’re experienced this industrial boom and, and economic well being and this upset Amérie, and he wrote this article, long essay, called Resentement, and he said, “I’m going to hold up a finger of resentment.” And he acknowledged, “I’m going to be irritating, because I’m going to tell you, you can’t move on. You can’t you move on, and you fundamentally violate something that you ignore our grievances you really knew or ignore our arm.” And it was it’s a powerful essay.

Rob Schneider 32:48

And I think that sort of holding up this finger of resentment is something that we have seen other people observe, have observed, for example, in truth and reconciliation tribunals in South Africa, in indigenous communities in North America and New Zealand elsewhere, where in fact, there is there is on the one hand, and this is something bishop to announce, he said, “we must move towards forgiveness, that we cannot have any sort of closure without forgiveness.” And yet there were people who had been tortured. And harm fundamentally said, “No, we’re not going to rush, you’re not going to rush to forgiveness so quickly. In order to get to forgiveness, you we have to forgive you.” And we are US deploying our resentment is a kind of an irritant. It’s not attractive, necessarily, but we’re using it as an instrument to watch your rapid move towards resentment without acknowledging our grievances.

Rob Schneider 33:48

And thereafter, again, it is an instrument of the weak. So we could see resentment, which again, come from Nietzsche and otherwise, is often seen as unappealing and attractive, just merely irritant, a complaint, a symptom. And here, it’s rather seen as productive, to force others to address the moral harms that have been committed. And without that, without addressing without acknowledging those arms, moving forward is fraud. And so it was really interesting to see how moral philosophers philosophers of various sorts have cultivated that and shown how this in fact, resentment has many different shades and degrees and measures of expression and purposefulness beyond what we see say in Nietzsche, or in our common vernacular emotional.

John Torpey 34:40

Right. Well, I mean, I think one might argue that our he ended up being the winner of that argument. And, you know, there’s so much attention now and in certainly in the post war period to this idea of coming to terms with the past, I mean, somewhere, I wrote about this, and I said, We are all Germans now, you know, there’s a way in which we all have blood on our hands. So we are pressed by various forces to come to terms with those tests. And in any case, I guess I never thought about it so much as resentment driven, but, you know, there’s surely something to that. So, well, thanks very much. I want to bring this episode to a close I want to thank Rob Schneider for his insights into the idea of resentment and its significance in contemporary politics. Look for us on the New Books Network and remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank the very well dressed Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance, as well as to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song International Horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying, thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.