From the Invention of Passport to the Golden Passport

In this episode of International Horizons, RBI director John Torpey interviewed Kirstin Surak professor at the London School of Economics, about her new book, The Golden Passport: Global Mobility for Millionaires (Harvard University Press, 2023). The conversation starts with the contrast of Torpey’s The Invention of the Passport (Cambridge UP, 2018) and the “golden passport,” which reflects how, in the past three decades, many countries have opened avenues for the wealthy to buy passports and citizenship (aka “citizenship by investment”). Surak discusses the creation of this market and the reasons why some countries are opening these opportunities. Despite not necessarily being attractive citizenship destinations in themselves, there is a hierarchy of citizenships whereby some countries like Turkey can be a citizenship option for citizens with less attractive citizenships such as Syria, Afghanistan or Iraq. Finally, the author delves into the political economy of citizenship for small countries and how it has become a source of revenue for a number of struggling small countries.

John Torpey 00:08

You may have heard lately about people with means – and sometimes criminal ties — “buying passports” or “buying citizenship.” It all sounds so counter-intuitive: isn’t a passport – or, more broadly, citizenship – a sacred possession of those born into different countries or who naturalized to the places they migrated to? How could such a thing be bought… or sold? The whole thing is puzzling. So what’s going on?

John Torpey 00:40

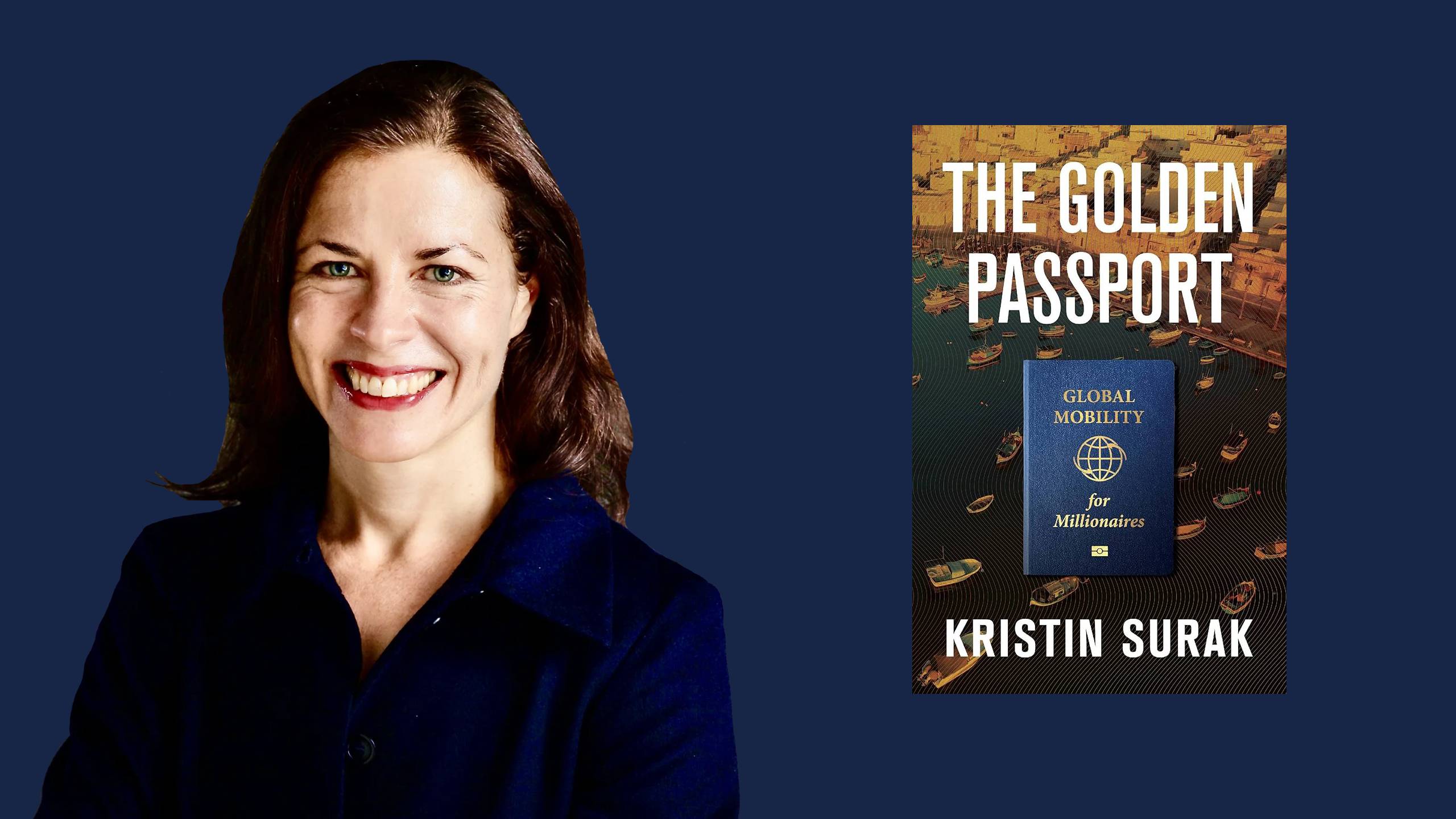

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. We are fortunate to have with us today Kristin Surak, Associate Professor of Political Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science and author of the newly-published book The Golden Passport: Global Mobility for Millionaires (Harvard University Press 2023). Her research on elite mobility, international migration, nationalism, and politics has been translated into a half-dozen languages. She is also author of Making Tea, Making Japan: Cultural Nationalism in Practice (Stanford University Press 2013), which received the Book of the Year Award from the American Sociological Association’s Section on Asia. In addition to publishing in major academic and intellectual journals, she also writes for popular outlets, including the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and Guardian, and comments regularly for the BBC, Bloomberg TV, and Sky TV News. Thank you for joining us today, Kristin Surak.

Kristin Surak 02:18

Thanks very much for having me.

John Torpey 02:19

Great. Great to have you and great to be able to talk about this really fascinating book. So as my introduction suggested, there’s something novel and perhaps certainly, to me a bit unsettling about these so-called “golden passports.” Maybe you could talk about how the market for these passports and for citizenship itself came into existence? Because I think that’s one of the most intriguing parts of the whole book really is where did this how did this become a market?

Kristin Surak 02:50

Yeah, thanks so much. It’s a great question. And I must, I must add too that, it’s kind of an honor to have that asked by the person who’s the author of a fantastic book on passports himself, namely, John’s book on The Invention of the Passport, which is really important, because of my own intellectual work and background looking at this, but of course, but John was looking at in the 19th century, in terms of the rise of passport is very, very different from this kind of world that I became fascinated by and started to explore this kind of world of golden passports, citizenship by investment, basically; countries that sell citizenship for you invest in the country in a certain type of investment, or donate a certain amount to the country, and you go through the background checks, and, and they make you a citizen. But that’s kind of the scene that we have now; there’s nearly a dozen countries that do sort of regular approvals of applications to these sorts of routes. But it took a while for the world to kind of get to this place. And one of the interesting things I found in doing research on this market is its origins, like how did we get there?

Kristin Surak 03:55

What I trace on the book is how… historically, there’s always some cases of effectively selling citizenship, you find it in ancient Rome, we find it in ancient Greek, a lot of European states, so that but that’s a little bit different from a modern country doing it. There’s a couple of outliers before but really, the storytelling kind of starts in the 1980s with Hong Kong. And what was really interesting in Hong Kong in the 1980s, is that it wasn’t clear that the entire colony would revert back to Chinese rule, that was negotiated in 1984, actually, that not just parked on the mainland, but also the island itself would go back and everybody in Hong Kong, so many people, started to panic. China at that point in time was much less capitalist than it is today, there were a lot of people making very good money in Hong Kong. They had a GDP higher than a lot of that of European countries at the time and people were looking for sort of “CYA” exit options, something that they weren’t sure what was going to happen and when it would revert back to Chinese rule.

Kristin Surak 05:02

And since some people look for a visa is in big countries like US, Canada was a really popular option as well. But other people just started looking for passports effectively. And a lot of different embassies started to oblige as well. And so it was a time when you found sort of different countries, different embassies sort of offering type of citizenship, it was really in the end, just the passport. And you could go get these deals applied or whatever. But they were really unstable. You know, a new government could come into power and basically just cancel the passport sort of erase all these citizenships that were issued. There would be cases of like, Tonga, where the King of Tonga got the ability to naturalize whomever he wanted and teamed up with some business people in Hong Kong and you could kind of bypass put off all the money, and the money ended up going to a bank account in San Francisco and even the ministry in charge of immigration, naturalization in Tonga didn’t even know it was going on. So it was really good, murky dodgy sort of seen there at the time. There are few other places to Taiwan, but what happened then is that you can kind of negotiate this and a lot of different places. But that’s a little bit different from really building a stable market around that, because for what actors in a market want is some sort of future security, like how do you know that the next government isn’t going to come in and just erase all the past parts, cancel all the passports and affect all the citizenship, so you want a really stable legal status have full citizenship. And so with that you can make it a marketable product.

Kristin Surak 06:55

So basically, different private firms, they’re a couple of key ones that went into small countries and sort of got them to make a more formal process. It wasn’t just negotiating with an official, they would bring in sort of a division of labor in terms of assessing the different applications gradually, they brought in international due diligence companies to run background checks on people, which can be hard sometimes around the world to figure out who is this person, what is their background, so they got experts to do that. And they made it a much more formalized process. And with a greater bureaucratic rigor, which meant that it wasn’t just getting a passport in exchange for cash. But there’s a whole legal thing behind it, which made it harder for effectively sovereign default, you couldn’t just default on the citizenships. If you tried to revoke the citizenship, somebody could challenge it in the courts. And so that was a big development in terms of the kind of formalization of the schemes. But, of course, people started making big money off of that, too. So this was, you know, countries could start making pretty good money off of it. Currently, about two of them, or three of them actually get more than 10% of GDP from this, but also for these intermediaries, the business is helping people apply for these, they were making a lot of money. So they started going around to a bunch of other governments, sort of touting these possibilities, kind of touting the words, “Why don’t you start up a citizenship by investment program. It’s like free money. You know, people just come and give you money, and you make them a citizen, hey, why not? What is there to lose.” And so we saw the spread of these sorts of programs in a kind of standard format. Across first the Caribbean, the Eastern Caribbean, a bunch of very small countries, microstates, with a population of less than a million, then Cyprus and Malta in the in the Mediterranean, got on board. And now several countries in Eastern Europe have put up programs, sometimes they’ve taken them away. And interestingly, now, we’ve got a lot of big countries getting on board. So places like Egypt, places like Jordan, and even Turkey, which is the number one seller of golden passports these days. So it’s really been quite an interesting transformation to watch. Or to trace, at least over the past 30 years.

John Torpey 09:16

Yeah, it’s fascinating, and just an amazing phenomenon somehow. And so it’s great that you’ve written this book about it. I mean, the centrality, seeming centrality of money to all this, I sort of suggested in my, in my introduction that this is part of what makes the whole thing kind of troubling, because we (at least I and you can correct me if I’m wrong) have this kind of notion of citizenship as I said, a kind of sacred position that not everybody sees it that way, I’m sure. But people like us tend to think of it in those kinds of terms historically. And so I’m curious, a lot of people, I think when they hear about this golden passport or citizenship by investment, they just think this is for wealthy international criminals. You know, the criminality is a pretty big part of this. So maybe you could tease out how much of this is about that and how much of it is really, you know, an opportunity for the wealthy to take advantage of this market opportunity that’s been created by microstates, and others who just kind of need the money.

Kristin Surak 10:30

Yeah, that’s a great question. And when I first got into the scene, I was learning in part about it because it was being covered in the papers. There were a lot of debates about Malta at the time, which was launching a program and this question of the country is potentially prostituting itself, it’s a way for criminals to buy their way in. And the media has been very, very good at uncovering definitely some cases of criminals or people with very bad backgrounds who shouldn’t have been approved. And, it’s been really interesting to watch that scene. But one of the things I found fascinating is that that’s not the majority of what’s going on, in fact, it’s only a very small part of it. And so I became kind of curious, well, what if you know, not everybody are criminals and it’s only a very small proportion? Why are why are people doing this in the first place? And, thinking about the different motives, there’s multiple ones. And they kind of turn on what you were kind of pointing out before in terms of the sort of identity or almost sacred status that a lot of people get the citizenship kind of purpose that is, I think, because of this association with the nation. Now, very often, when we talk about, in social science, of course, we talked about nation states, this kind of whatever 19th century form that’s become hegemonic across the world, you’ve got a state, that in the sense, the government rules in the name of the nation, whether it’s even democratic or not, or so. But you know, those two parts come together to form what most people talk about it in terms of being a country.

Kristin Surak 10:30

I see .So maybe you could tell us just some of the details of how this works. Okay, you’ve got this Pakistani guy who’s got this globe trotting kind of job. How much does this cost him? And what does he do? Does he you know, buy the passport of St. Kitts and Nevis and move to St. Kitts and Nevis? Does he ever go there? Does he vote there? Does he have any real relationships? St. Kitts and Nevis?

Kristin Surak 12:06

But in this case, the sale of citizenship, it’s not about membership in the nation. It’s about the rights you get from the state. So it really kind of separates those two, those identity issues are not a question for anybody involved in this in that scene. But what people really want, then are those rights in the state, which number one are mobility, visa free access, there’s been a lot of talk around visa free access to the EU. And that’s been very important, especially for some of the small countries in terms of the value of the “product on offer.” But it’s not only that, because as I mentioned before, Turkey is half the global market right now and it doesn’t have visa free access to the EU. So what you can ask is why would anybody want citizenship in Turkey? Well, it’s better than having a Syrian passport and Iraqi passport and Iranian passport, Afghani passport. And so they see a lot of demand from other countries that are sort of lower down on what might be seen as kind of a citizenship hierarchy, because it’s still a little bit better. And of course, in all these places, the countries themselves are not as wealthy overall as a place like, say, the US, but you do have successful middle class, successful upper middle class, successful upper class people who can afford these things.

Kristin Surak 13:23

So, one of the interviewees I met for example was from Pakistan. He had a PhD, he was a head of tech sales for a major company, and he was based in Dubai. But he could only traveled to 33 countries visa free, which is a problem for him for his job. And he had sort of big industry conferences around these things, and he sort of shopping around for his different options, so that he could have better mobility so that could be visa free access to the EU, or it could just be an easier time applying for a visa also. So that’s number one. Then you got people who are… it’s kind of an insurance policy, it’s sort of like the potential of mobility in the future, especially if people are from authoritarian regimes. They’re not sure what the government’s gonna do next. COVID-19 highlighted this for a lot of people, they just weren’t, weren’t happy with what their home governments were doing and wanted to make sure that they’ve got exit options for the future. And what’s been really interesting in watching this thing is that it’s no longer just people from the global south with “bad passports” but also US citizens. The hyperpolarization of politics in the US, along with the COVID 19 pandemic set the number of US citizens apply for these things. When I started studying this in 2015, there were no US citizens, it was really people just trying to shed the tax status of being a US citizen. But at since COVID-19, and since this hyper politicization of elections, people are going, “I want out,” I’m not sure what’s going to happen next. So the insurance policy part is really important too.

Kristin Surak 15:25

Yeah, great question. I mean, what’s interesting and looking at these programs, and some of them, but most of them, people don’t want to move to these places. I mean, they’re often small islands. And I remember going around doing fieldwork and then when I went over to Vanuatu in the Pacific, and I would ask people what do you think about the citizenship by investment program, they’re like, who wants to buy citizenship here? We all want to get out of here. There’s nothing to do. And if you think about it, you might be thinking, oh, yeah, beautiful tropical beach, that sounds great. But you know, after a couple of days of that it can get kind of boring, especially if the country is about 55,000. People, even if you are a really big Time Surfer. So the place where these people are not looking to go to in the main are the countries selling citizenship, they want the rights that citizenship gets you outside of the country, which we usually don’t think about when you think, think about those rights inside the country. But citizenship is a sticky status that follows you to wherever you go and that brings different rights and benefits outside of that country to now. Turkey is a little bit different because you do get people who want to be there. It’s a big country, a symbol, it’s a big city, there’s business opportunities, etc. But for the most part, people aren’t going, which could be good for the small countries too, because you don’t have a lot of the friction that might arise if you had a bunch of wealthy people from elsewhere in the world suddenly joining the country considering also that they can’t vote, because most of these countries have laws that require you to be resident in the country versus a period of time before you vote. But what you have to do is you get a lot of paperwork together in order to do these programs. You have to show like, your tax statements, how you’ve made your money, birth certificates, police background checks, certificates, whatever for different places where you lived and all of that and put them together in a big file. The countries assess them, how they do that can vary country to country, whether they’re more formalized, or other. I mean, there’s still some cases of these sort of dodgy things on the side that are questionable. Like the Comoros, for example. They sold a whole bunch of citizenships particularly focused on a Middle East market. But, you know, it was mainly a passport and now they’re not renewing the passports and they’re disavowing all these people. So that stuff still happens. But you know, for the countries themselves, they can be huge moneymakers. A real difference in terms of what it brings in.

John Torpey 17:46

So how much is somebody paying for one of these things? And how does that vary? So the low end is about 100,000. US, and that’s for citizenship in a Caribbean country. And then the high end is about a million or a little bit more than a million, which would be Malta. And if I were to go for one of these, if I had the money, it would definitely be Malta, because you’re not just the citizen of Malta, but you are an EU citizen. So you can move anywhere in the EU, you get full rights and benefits that you do. And you know, all across the European Union, you can move to Paris, put your kids in schools get a job, do whatever you want, it’s a really powerful citizenship status to have, which is why Malta can charge 10 times more than Dominica for what it’s doing. But most probably right now is Turkey 400,000: Buy a nice house in Istanbul or on the beach on the Mediterranean and Turkish citizenship as yours.

John Torpey 18:41

No surf in Turkey. But anyway, that’s another problem. In any case, I want to get back into this question of the meaning the sort of nature of citizenship as a status. How do you see this development as affecting what I’m describing as the kind of sacred status of citizenship? Is this something that we’re going to be seeing more of is this. I mean, people have talked a lot, as you know, in recent years about sort of the idea of the meaning of citizenship, that there’s lots of emphasis on rights, but very little emphasis on obligations, and this would seem like, the quintessential example of that. Is citizenship thinning, is this kind of indicator of where things are going, are things going to keep going in this direction, or is there a kind of limit on the spread of this kind of market? I mean, could you talk about that a little bit?

Kristin Surak 19:46

Yeah, that’s a great question, too. Because, you know, there’s a big geopolitics to this as well, you know, in a sense, it’s uncertainty that creates a lot of demand, you know, there’s inequalities between citizenships and what those citizenships get you, but it’s also global uncertainty, like not knowing what your government is going to do without knowing what the next pandemic is going to bring, etc. But at the same time, there’s a big geopolitics as well. So right now, the European Union, mainly the European Parliament and the European Commission have been doing a lot to pressure countries with these sorts of programs, to end them, shut them down, etcetera, it’s been able to threaten to revoke visa free access to a number of countries and it has done so with Vanuatu because it was sort of playing fast and loose in terms of its vetting of different people. And so how sustainable they are, is a big question. But the real player in background of all this is the US government, to be honest, and the US government has a lot of power over these programs, but it sort of watches them and is a little bit more quiet. It’s a little bit like a parent, watching a teenager sort of experiment with smoking, where you think if you’re going to crack down on it, you might actually drive it drive the country into something harder, or worse off, but you just kind of want to monitor it to make sure it doesn’t go too far off tracks. And so there’s a big geopolitics to it, which can affect demand. There’s been a lot of other countries that are in talks about getting these programs on board, but usually they are in the Global South. I think that’s part of the impact of the EU’s pressure on these sorts of programs. So I think supply will continue to expand because it’s an easy way to get free money and demand will probably continue, as well, just because there’s all sorts of uncertainties in the world and the inequalities between citizenships are very unlikely to go away. But yeah, it’s sort of an interesting kind of counter direction, because on the one hand, we see nationalism and national identity is having very, very strong resonances with a lot of people today. But people can also be very strategic about citizenship and membership when they need to and states can be very strategic about that, as well. And I think that will continue.

John Torpey 21:57

Right. So I mean, since you have kind of written a book about a market that came into existence, because people made it, I’m sort of curious, since you seem to have a bit of a crystal ball, like, are there other things like this, that we should be paying attention to? I mean, I’m struck by the I the phenomenon of Bitcoin, which maybe this is not something you want to feel like you really can talk about, but it does sort of strike me that there was all this hype about this thing called Bitcoin, nobody could really understand what it was, and it was, but it was supposed to serve various kinds of purposes. Although, it seemed like, in a way, it was only really good for drug dealers and so that was a bit of a problem. And now there’s this guy sitting in jail in the Bahamas, I think, named Sam Bankman-Fried, who, I don’t know, maybe it’s just ordinary old fashioned financial fraud, had something to do with Bitcoin. So are there others? I mean, do you want to comment on the Bitcoin phenomenon? First of all, and second of all, are there other things that you think are maybe more promising? You could advise us all on how to get rich before we get in on the ground floor.

Kristin Surak 23:15

I need to find my crystal ball because it’s not something they issue to every single social scientists,. I always get the impression that the political scientists are the ones that the crystal balls, but I suppose thinking also about Bitcoin and cryptocurrency one of the interesting things in watching that market, and I sometimes came across it when I was looking at the citizenship stuff, because people would ask, Well, can I buy citizenship with Bitcoin? And what’s interesting with that is it’s a way for people to have financial transactions that are in a non-sovereign currency, it’s a way to untether themselves from states, and potentially the states watching them in the rules that states can implement over financial transactions. And so in a way what I look at in terms of citizenship by investment is what the way that people also want to avoid the hurdles that states throw up in their in their way in many cases. Well, what’s interesting in looking at that, though, is that, especially with global capitalism still needing states because states defined jurisdiction, you need the rule of law in order to protect private property for capitalism to work, for example. And so for me, it’s kind of interesting to watch because citizenship is a sovereign prerogative, that brings the state back in from the first place, you’re not going to escape it terribly. But it becomes a way of, in a sense, loosening that sort of grip or multiplying people’s options in the face of states and that kind of rolls into that pulling out the crystal ball. What’s up next, at least in terms of my own research, which is also often underscored by what a great places to travel to, which is looking at digital nomads programs, because it’s a situation in which countries are competing for very desirable populations. They try to attract mobile, highly educated people highly compensated people for a short period of time, and then let go of them again. And those mobile, highly educated, highly desirable people also choose among states. So you get a market with two moving sides, both demand and supply are kind of checking each other out and deciding where to go, which completely flies in the face of sort of the standard image of the world that we get by looking at a Mercator projection of the globe, on a map on the school wall, where you have, you know, these different countries with clear borders, single colors on the inside, and the idea that people are inside “their countries” as well. So I’m interested in the development of that market, which I think will only grow.

John Torpey 26:03

Sounds intriguing. Well, I look forward to that book when that gets done. But in the meantime, your comments about the state and my question about the sacredness of citizenship because people are supposed to participate. I mean, in the ideal kind of Greek policy idea of states people are supposed to participate, they’re supposed to rule and be ruled, and all those kinds of things. And states are important, as you say, inupholding the rule of law. I mean, I was just reading something about Guatemala, where our fellow sociologist, Bernardo Arevalo has just been elected president. And, you know, one of the things that he seems to want to do is strengthen the rule of law, basically, I mean, these, in other words, he ran against Corruption, of which, you know, there’s plenty in Guatemala, and that’s what the forces of corruption have done, they’ve eaten away at the state. And, he’s trying to sort of restore its stability. So, I mean I guess the question I want to ask has to do with the nature of contemporary inequality in the globe, and its relationship to these kinds of state hollowing kinds of phenomena? I mean, is that something that you think is going on? I mean, how does this reflect the nature of contemporary inequality, I guess, is what I really want to ask.

Kristin Surak 27:41

Yeah, that’s a really complicated one, because it’s one of those where I think the general assumption about the scenery, probably the one I had, when I first started looking at it is yeah, this is just rich people buying their way in. But you actually see global inequality coming up in multiple ways, much more complex ways as well, because on the one hand, of course, you have the intricate in country inequality between the rich and the poor, people who can afford this, whereas a lot of people can’t, but then you also have the inequalities between countries in terms of the options that citizenship gets you and as long as citizenship is attached to mobility and border controls, those are very, you know, you don’t get a choice in that; where you’re born Ayelet Shachar calls it “the birthright lottery,” you’ve got this, you’re lucky to have been born in a very wealthy country, you get a lot of what might be known as passport privilege. And that’s very hard if you were less likely, you know, say you were born in Nigeria, it’s much, much harder to travel. And it could be it. And I remember even a colleague who was a Harvard PhD working at NYU, who was invited to give a keynote in France and started the visa application process three months in advance, giving all of her bank statements, everything else. And in the end, they didn’t get her to visa in time. So she was faced with that simply because of her country of birth.

Kristin Surak 29:04

And then I think you get to look also at the geopolitical inequalities, because most of the countries traditionally doing this are small microstates. And they live in the shadow of much bigger global players, whether it’s their former colonizers, like in this case, are all largely former British colonies, or whether it’s the US, which controls the global flow of dollars around the world in which these countries are dependent, can also be the IMF, they often have IMF loans over the European Union, which controls the value of their visas. It’s not they can’t just simply say we’re going to build a citizenship policy and sell it and do it on our own and ignore these other factors. So for example, a lot of those countries, especially in the Caribbean would love to naturalize Russians. There’s a big demand around Russian citizens for alternative citizenships right now, and not all of them are Putin supporters. In fact, there’s many of those who are leaving the ones who are voting with their feet and leaving who are looking for these options. But the U.S. said, “you cannot naturalize Russians.” And the stakes are so high for these smaller countries that they fall in line and do what the U.S. says, even though the US will still give Russian citizens a visa, U.S. will still naturalize Russians themselves.

Kristin Surak 30:13

So you get to see also these geopolitical power plays over what is at the heart a sovereign prerogative. And, you know, so in that sense, it’s really fascinating to watch just how globalization really works in the end, and it really does ride on a lot of inequalities.

John Torpey 30:32

Right. Right. So I mean, I guess the other question that then occurs to me is how much does this discussion that is partially connected to our friend Dimitry Kochenov and sort of quality of nationality index, I mean, are those things, exerting pressure on any of the countries who don’t score so well to be better states, to be more responsive to their citizens or to create economic development or anything that might act in a way as some kind of resistance to having to go down the passports for sale road?

Kristin Surak 31:12

Yeah, that’s a great question, too. I mean, one of the things that I’m doing some research on right now is looking at the economic outcomes, or the economic impacts of these programs. And part of that is also looking at that, do we see a shift in the quality of governance in these countries as well over time? And I haven’t finished that, I think it’s a very interesting, a very important empirical question. But also, one, what’s tricky in looking at microstates, these tiny, tiny places, is that the data usually aren’t very good. Even in big international surveys, the data tend to become so small. If you think about a country with 80,000 people in it, it doesn’t take much to move the needle in one direction or another. So it can be really tricky. And in terms of quality of governance too, these are, these are big amounts of money for a country that size and moving through those programs. And not all of it always ends up in that country or building the economy in a way that’s really productive. For these places, in a way there can be some similarities, for example, with foreign aid, we’re not all foreign aid ends up building a country in the right way. That a lot gets siphoned off on the side, it gets spent badly, it goes off and fees. So, you know, whatever Western powers that are supposedly implementing the companies and stuff like that. So, in that sense, the scene also looks like that as well. There’s a lot of ways in which these programs can be tightened up and improved if in terms of the potential economic impact, and then, maybe get them off of this as a lifeline.

John Torpey 32:48

Right, interesting. Well, alright, so fascinating book. I know, we’re sort of out of time, but I want to thank Kristin Suruc for her insights on The Golden Passport, that’s just the title of her new book, and their significance in contemporary society. Look for us on the New Books Network. And remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance, as well as to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song international horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying, thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.