Negotiating Decolonization

The Limits of a Fairy Tale with Valerie Rosoux

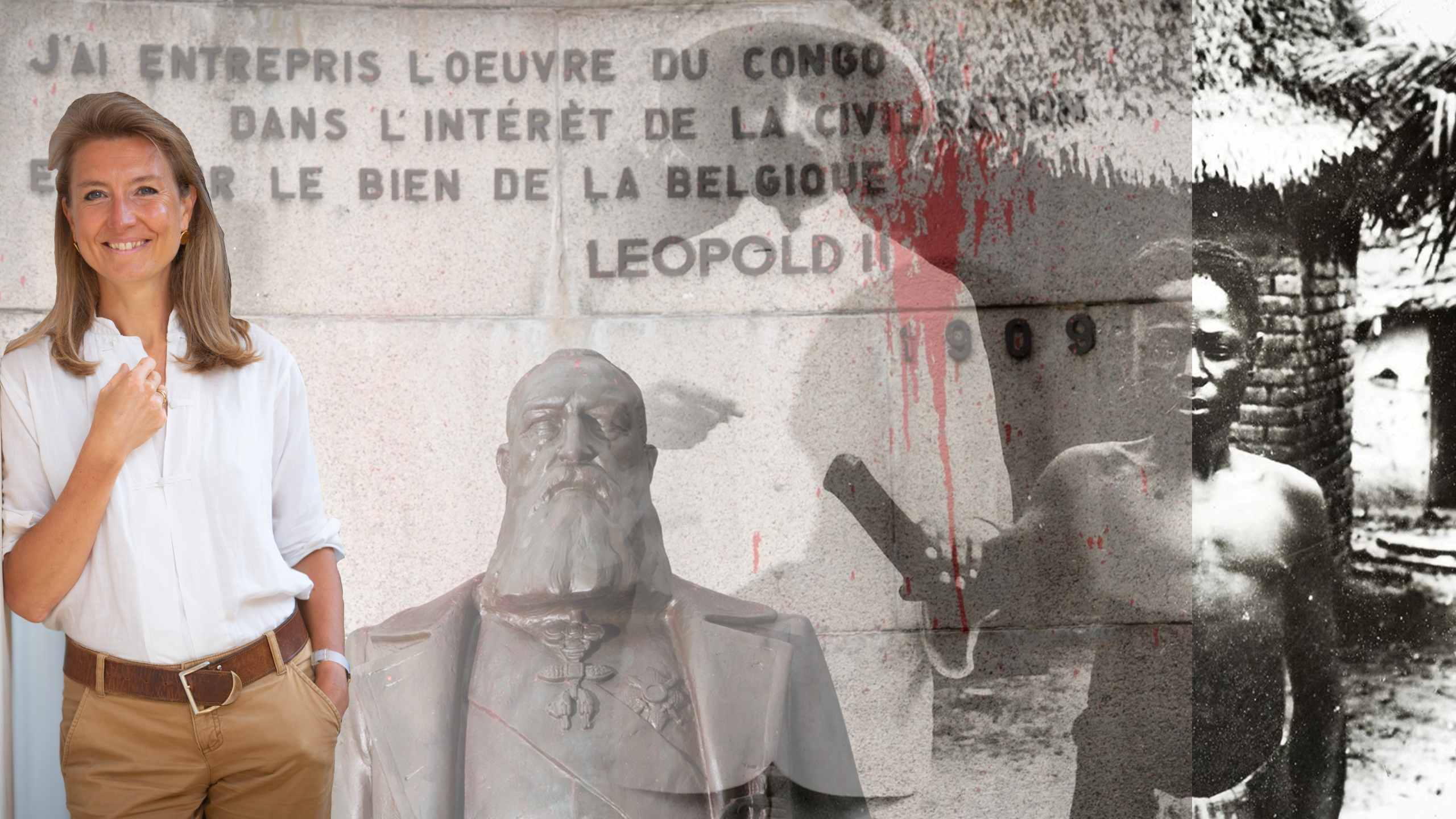

In this episode of International Horizons, Valerie Rosoux, Research Director at the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS) discusses the disagreements in the historiography of Belgium’s human rights violations during its colonial activities in Congo, and how Belgium’s case differs from those of Netherlands and France in coming to terms with their colonial past from the perspective of the elites’, religion, and parties. In dealing with these, she argues that had Belgium’s politicians known the literature and focused on solving the inequalities of the present, they could have been more effective.

Moreover, Rousoux claims that the Black Lives Matter protests informed the narratives around past colonialism and discrimination in Belgium, although Belgium’s civil society’s claims haven’t been completely addressed. Finally, the author analyzes how historical figures such as Victor Hugo are deemed as racists, and the richness of these views outside scholarly paradigms.

Transcript

John Torpey 00:02

How are former European colonial powers coming to terms with the colonial past? This is particularly an issue in Belgium in the aftermath of King Leopold II’s depredations in Congo. But what about other countries? How do they compare? And what does all this have to do with the reckoning with race in the United States, in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter, the George Floyd killing and other cases of police brutality?

John Torpey 00:30

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey 00:50

And we’re fortunate to have with us today Valerie Rosoux, who is a Directice de Recherche, Research Director, at the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research, the FNRS. She has a PhD in political science and teaches international negotiation, transitional justice at memory politics at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium. Her research interests focus on postwar reconciliation and the uses of memory in international relations. In 2010 to 2011, she was a senior fellow at the US Institute of Peace in Washington, DC. Since 2016, she has been a member of the Belgian Royal Academy. In 2020, she was awarded a Max Planck Law Fellowship, which is a multi year project that has enabled her to form and lead a research group on memory and transitional justice. In 2020, she was appointed by the Belgian Parliament to serve on a commission to deal with the colonial past and was the only expert who participated in the writing of both the initial and the final reports of the parliamentary commission. That was in August 2020 to December 2022. She’s currently working on a book provisionally titled Negotiating Decolonization: The Limits of a Fairy Tale based on her long study of this important historical process. So thanks so much for being with us today Valerie Rosoux.

Valerie Rosoux 02:29

Thank you, John.

John Torpey 02:31

Great to have you. So your work recently has been focused, as I said, on coming to terms with the Belgian past, in part as a result of this commission by the Belgian Parliament, and as I said in the introduction, this had a certain amount to do with the period of King Leopold’s rule over what was essentially his private domain in Congo. So, can you tell us where the discussion about colonialism and decolonization stands in Belgium?

Valerie Rosoux 03:05

Yes, yes. But until the independence of Congo, Belgium school’s textbooks underlined that Belgium has the administration of the territory, eighty times its size [and] was a modern colony. And there was a no single reference made to the widespread violations of human rights. After the independence, there was a kind of concealment policy. The idea was okay; the colonial past is completely past, it’s history. These words were soon contradicted, of course.

Valerie Rosoux 03:42

In 2000, a new government encouraged a critical acceptance of the country’s colonial heritage. They launched a parliamentary commission to determine the exact circumstances of the murder of Patrice Lumumba, who was the first Prime Minister of the Independent Democratic Republic of the Congo. [He] was assassinated in 1961 with an implication of Belgian political responsibility. So the commission’s report led to official apologies at that time by the Foreign Affairs Minister. That was okay.

Valerie Rosoux 07:01

Then, this critical approach was overturned with the appointment of a new Foreign Minister, who wished to put aside this “misplaced”. This is his word, “the misplaced feelings of guilt.” And four years ago, the Belgian government launched another parliamentary commission, so you see highs and downs in terms of evolution of the official perspective on the past. So a few years ago, the Belgian government launched another parliamentary commission devoted this time to the specificities of the matter.

Valerie Rosoux 07:01

At the end of the process, the Prime Minister apologized for kidnapping, the segregation and forced adoption of thousands of mixed-race children from Belgium, Colonial Africa. And then the last step, if I may say so, in 2020, as you said, the government set up a new parliamentary commission. Multiple ambitious decide, since its objective was not to deal with a particular event, but with the whole colonial past in the three countries of the African Great Lakes, Congo, Rwanda, Burundi. It did last two years in the House. And the organized hearings, more than 150 witnesses, academics, artists, diplomats, militants as well shared their views [and] their expertise within the parliament. Everything was transcribed and videotaped. And the same number of people met with the Belgium delegation of MPs who went to Kinshasa, Bujumbura and Kigali last September. Their expectations were also notified and reported to the parliament. And last November, a list of more than 100 recommendations was presented by the President of the Commission. They needed to be negotiated, and [there was a] big surprise: after six intense weeks of negotiation, the political parties present at Parliament could not make any deal. So the the outcome of the whole process was zero recommendation, just as a kind of summary of the where we are now.

John Torpey 07:04

So you make it sound as though — and the article you wrote that you sent me suggested that — this is not exactly a satisfactory resolution of this process. And I wonder what you can tell us about why you think that’s the case. And you mentioned at one point in the article, the fact that has always kind of struck me about Belgium, which is this fact that it always seems on the brink of dissolution itself. And you sort of suggested in the article that may have something to do with this not entirely satisfactory resolution. I’m sort of curious since that’s a relatively unique feature of Belgium’s existence, maybe that is kind of a key to, larger processes. So maybe you could talk about why this has turned out the way it has.

Valerie Rosoux 08:00

Well, I don’t know whether it is more difficult for Belgians than for French or Dutch people to come to terms with their colonial past. I would say yes or no. On the one hand, they are some specificities you are right, which are related to the tensions that the Belgian national identity, which is a fragile identity. I remember 10 years ago, when I was in DC, living there with kids, the first time I saw the kids pledging allegiance to the flag of your country, I felt a sense of shock because I didn’t have the concept of a strong national identity. So the national identities in Belgium is fragile. And they are, I would say, maybe four main tensions that are recurrent, that are really underlying the whole political debate in Belgium.

Valerie Rosoux 08:59

The first one is, of course, French speakers versus Dutch speakers. And here, there was an impact on the commission because some nationalists in Flanders explicitly said “well, in the Congo, it was not us. It was all the responsibility of the French speaking elite.” Right. So [this was the] first tension. The second one is the tension [of] Catholics versus secularists. It seems a bit old fashioned, but still, I could feel this influences well during the hearings. Some were symbolically saying “we don’t have anything to do with the Congo because it was about the Church and the Church was guilty therefore it still guilty.” Second tension. The third tension is the left wing versus right wing political parties, [which is] something that you have in your country and in France as well. But it had an impact because once again, some people could say, within the parliament, “it was not us in the Congo, it was the capitalist elite. These people were exploiting the Congolese as they were exploiting the poor Belgians here, and their descendants must pay now.” And the fourth tension that I was thinking about is the tension between opponents versus defenders of the Royal Institution. It’s not so important, but I think that clearly, at least for some nationalist in Flanders, they had another agenda, and then just dealing with the colonial pass. So it’s an explosive cocktail, if you want. But this is one part of the of the explanation. I think that on the other hand, one can hardly deny the fact that it’s not completely a taboo; they are plenty of academic books, articles about the colonial past. Even though the textbooks are not transmitting a lot of information, I think. What I was seeing on the other hand, is because Belgium faces the same difficulties, the same challenge that France, Netherlands and so on [do] about the fact that it’s not only about the representations of the past, but it’s the debate about the representation of the other. It means racism, and above all — and this is where it is difficult — the representations of one’s own group. And I think that the challenge is the same for all the metropoles; we have to open our eyes on the fact that we were not on the right side of history. A bunch of this, I would say this is quite difficult because there is this narrative, which is a bit the narrative of the “poor little Belgium during world war one that needed to be saved by Irish and British soldiers.” This victimhood sense of sort of buffer zone place invaded by all the powerful countries around. Well here, the scenario was really completely different. So I think that takes time to accept that.

John Torpey 12:32

Interesting. Obviously, I’m interested in the way in which the Belgian story compares to what’s going on in France or Germany, which is, as you probably know, having its own fairly extensive and kind of unprecedented discussion. Although it’s been going on for quite a while, really, about its colonial past, which was a minor issue, when I certainly when I first started going to Germany in the early 1980s. It just wasn’t something that people talked about. Gradually, historians started to talk about what had happened in Namibia, in German Southwest Africa. But it wasn’t really a political issue, it was sort of an academic issue for a while. And in the intervening or the last 20 years or so, it’s become, I would say, increasingly, and in some ways, a kind of insoluble problem, it seems to me. Yoshika Fisher, the one time 60s radical, who became the Foreign Minister of Germany, said “we’re not going to choose sides, which group gets the money that we’re going to give you, we basically see ourselves as responsible for exploiting and under developing Namibia. So we’re just going to give it to the country as a whole.” And [he] says that’s it? Well, that was not it. And the issue continues. And I wonder how resolvable in a way are these matters. Can there be a resolution of the of this unpleasant test?

Valerie Rosoux 14:18

That’s interesting, what you’re saying. I think that at the beginning of all these kinds of processes and negotiations and committees, there is, in most of the cases, I know, very good intentions, but also maybe very naive intentions, in the sense that there is a kind of premise, which is at least it was a case in Belgium for sure. It was so ambitious, over ambitious. The premise was “okay, we are going, my group, my party is going to fix past and past and current discriminations.” No, we’re not going to fix anything like this in a commission that will last a couple of months or even two years. In this sense to me, it’s not solvable. Absolutely, you’re right, doesn’t mean that there is nothing to do, and that it’s not urgent, but it’s a very long process multifaceted, multi level processes.

John Torpey 15:26

Right. It’s struck me, I guess, since I started working on these issues, which is what led us to meet eventually. You know, how difficult it is to resolve the past and claims are made about the degree in the United States, for example, the degree in the 1619 project. The claim is made that the history has not been told truthfully, which I find a claim that’s very problematic, [It] impunes the intentions of generations of historians. Some of whom did right, of course to justify the lost cause, so-called “Lost Cause of Slavery of the South of the Confederacy,” etc. But it’s not necessarily a good characterization of a lot of the other history that’s been written. So in any case, I think it’s just very difficult to resolve claims that are sort of more or less expansive and difficult to pin down. And I guess my tendency has come to be to think about this in terms of the present and try to rectify inequalities in the present, leaving aside exactly how they got to be what they are, because that’s going to be a matter of sort of interminable controversy, it seems to me. I mean, does that seem crazy to you?

Valerie Rosoux 16:59

Yeah. I am completely on the same wavelength as you, but I read your book. So I was trained on, I grew up with your books. I wish the Belgian MPs knew your books, because they would have been much more efficient, I think. No, but the question is really about the present tensions and discrimination, for sure. But the fact, as I said, this reaction of almost all the parties in Belgium “it was not us,” and then they have their guilt targeted. Maybe not to get good. Maybe they were, to some extent, right. But so I think that it really would help to be aware of all these other agendas going on at the same time.

John Torpey 17:54

All right. So thank you for the plug about my books. But speaking of influence coming from the United States, I’m sort of curious; all of this is kind of unfolding in the European context largely around the colonial past and these various countries. But it’s all unfolding in kind of the context of the sort of racial reckoning, as it is sometimes referred to in the United States over the killing of black typically black men, although some black women, of course, particularly by police. Although the Trayvon Martin case was not about the police. It was about a vigilante, basically. But this process has been underway for 10 years in the United States. And I’m curious how you see that see what’s going on in the US is kind of influencing these discussions and developments in Europe.

Valerie Rosoux 19:00

There is a direct and explicit relationship between both continents in disregarding both phenomena. In Belgium, it was particularly the case after the murder of George Floyd. This, I don’t know whether in the US you realize that, it was literally a wave of reactions in the world, at least in Europe, this Black Lives Matter movement. In Britain, it impacted the political scene in a very obvious way, in the sense that on the the seventh of June, a big demonstration brought together more than 10,000 protesters in Brussels. Despite the severity of the sanitary confinement, it was really the pandemic time and 10,000 [people joined]. This number can seem ridiculous for you in the US because you know, it’s a big country. But for us, in Belgium, 10,000 people during the pandemic, it revealed something. And so it was explicitly about George Floyd and Black Lives Matter. And then a couple of days later, King Philip marked the 60th anniversary of the independence of the Democratic Republic of Congo, expressing his deepest regrets. These are his words, for the acts of violence and the brutality inflicted during the colonization, it was the first time that that his words were so clear. And 10 days later, the Belgian Parliament established a commission, which was a kind of path. So the pace of the decisions that follow the Black Lives Matter was very fast. And the link between the two phenomena, so racism in the US and then discussion of colonial legacy in Europe, was also made explicit during the hearings. I attended all the hearings during the year, in the framework of all the theories devoted to current discriminations, almost all militants, not only the afro descendants, refer to the murder of George Floyd to describe Orpheus continuity. They could see between the colonial despise towards the Black individuals and the correct discrimination. So the relationship was absolutely direct, even the vocabulary, the grammar was common. And the expectations, the demands were sometimes the same, because they wanted to an anti-racism plan. That was one of the recommendation, but it was not agreed because of the lack of compromise yet, but it was a major expectation among Afro descendants.

John Torpey 22:06

Right. But as you just said, there’s a kind of distinction in the US, it’s about racism and in in Europe, and Belgium, certainly, it’s primarily about colonialism and its effects. But of course, colonialism didn’t stay in Congo, many people from Congo and elsewhere in the African Great Lakes region, where Belgium had colonized, are now residents of Belgium, and France and other places. So I’m curious how this process which was so heavily influenced by the George Floyd murder? How is that affecting the way, Belgians and Europeans think about these questions of race? And I think it’s become more — tell me if I’m wrong — but my sense is that it’s become more of a question of racism in the European context. And in a certain way less than the issue of colonialism has, in some sense kind of receded. This is not going away. I’m not suggesting that. But in other words, race as a kind of dividing line, the way we think about it in the US, I think, has come to be more pervasive way of thinking about things in Europe as well, is that…?

Valerie Rosoux 23:38

Yeah, absolutely. I think that the emotions that were present throughout the process. The emotions were very intense during the hearings, in the media, in the newspapers, the testimonies, everything was quite emotional in all directions. Grief, a sense of guilt, a sense of shame, rage, or even hatred, and everything was with they’re very intense. And I think that for most, I don’t know, I cannot speak on their behalf. But if I come back, if I remember what was said during the hearings, it was, above all about the current discriminations with which means about racism now. And in this regard, it was completely similar or product parallel to what’s happening in the US. So we all face I think the same challenge and the same emotions to appease in a way or another

John Torpey 24:57

Right. So you also mentioned in your article, sort of interesting episode, in which you had used a quotation from the writer Victor Hugo, that seemed to you to speak to the circumstances of the situation you were trying to describe and make sense of. And then somebody in the commission that you’re involved in the group that was working on these problems said, “Victor Hugo was a racist and I would prefer if you don’t use that quotation.” And I wonder whether that’s really the way we can resolve these things. That is, I don’t know exactly anything about Viktor Hugo’s racist qualities, I don’t know anything about that as apparently you did not, either, when you quoted that passage. And I guess the question is, whether anybody who’s had any kind of things that they’ve said wrong, and, or that we now regard as unacceptable, is unquestionable, so to speak, or whether we don’t have to sort of recognize that people have complicated qualities and characteristics. And there’s this kind of issue about throwing the baby out the baby with the bathwater. I didn’t know anything about I don’t know that much about Viktor Hugo in the first place. But sort of to make that aspect of his past somehow absolutely disqualifying. I don’t know who will survive that test in so at some point would not…

Valerie Rosoux 26:51

We would not, no. it’s a very emblematic anecdote. Indeed, what happened is that I was in charge of writing the common introduction of the first report. So each chapter was signed by its own authors, because they were as well tensions between us. Since we were coming from different worlds. Some were academics, other were representatives of Afro descendant communities. Others, were coming from Burundi. So it was interesting in this regard. So it was not basically the very easy academic comfortable words [where] everybody speaks the same answer. However, it was a challenge. And so when I quoted Victor Hugo it was a single sentence. The sentence, I thought, was inspiring. And it’s still to me, which is the debt are invisible, they are not absent. And the point that I wanted to make was that, “okay, we see people here at the negotiation table during the hearings, but there are many other people here at the parliament, in people’s mind.” So we were not only the people concretely here now visible. And I thought that it was relevant. But I felt so surprised when I immediately received the email to tell me stop, it’s a negotiable. We’re not going to quote Victor Hugo in the introduction. Then I didn’t know because I didn’t know the passage that was wrong and that was explicitly racist. So why don’t I confirm that? It was not a completely ridiculous remark. So I thought about your sense of nuance, okay. But we could still keep [it]. But to be frank, this process was so interesting. For me, it was a learning process in terms of positionality, in terms of reflectiveness, or authority reflexility. But it was also demanding and I felt I’m not going to fight all the time. If it’s a problem for one out of 10, It’s enough to erase the name because I had plenty other potential quotations if you want. But that was this question of legitimacy of the experts is also a big part of the game. And it was not easy. I don’t know whether it can be longer, but it’s another chapter of the this long adventure,

John Torpey 29:37

Right. It obviously is a challenge to sort of figure out how to negotiate these kinds of situations. And I think it’s going to be difficult for all of us in some ways to try to figure out what some people may find offensive and that we had no idea of. And maybe that will reveal sides of these people that we had known and that sort of thing. So in any case, it’s going to be an interesting challenge as you say. Thank you for talking to us about what you’ve been doing.

Valerie Rosoux 30:15

Thank you for having me.

John Torpey 30:17

In the Belgian Parliament, and we look forward to hearing more as you proceed. But that’s it for today’s episode. I want to thank Valerie Rosoux, for sharing her insights about coming to terms with the past in Belgium and beyond. Look for us on the New Books Network. And remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance as well as to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying, thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.