The Everyday Feminist with Latanya Mapp

Equality between the sexes has long been recognized as a fundamental moral and legal objective of the UN, and more recently of many governments and international financial and development institutions. Women’s Empowerment has long been recognized as essential to the larger development objectives of the UN and the international community. Extensive empirical data from all over the world today informs and supports the thesis that countries and regions just do better when women are educated, formally employed legally secure and politically well represented. In this episode of International Horizons, Ellen Chesler talks with author Latanya Mapp about the effects that investment in women led initiatives have for the world.

Ellen Chesler 00:00

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is Ellen Chesler, and after a long career in academia, government philanthropy I am currently a research fellow. And in the past few years, I’ve had welcomed a number of women to this podcast, inspiring leaders from the United Nations and from prominent nongovernmental organizations, as well as distinguished academics were writing about the growing importance of considerations of gender in foreign affairs and global development.

Ellen Chesler 00:41

Equality between the sexes has long been recognized as a fundamental moral and legal objective of the UN, and more recently of many governments and international financial and development institutions. Equal rights for women were inscribed in the UN Charter in 1945. In its foundational Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and other standalone convention, the visionary Convention to Eliminate all forms of Discrimination Against Women adopted years later in 1980.

Ellen Chesler 01:12

Women’s empowerment has long been recognized as essential to the larger development objectives of the UN and the international community. Improving women’s status is not just the right thing to do, as Hillary Clinton likes to say, but also the smart and essential thing to do if we hope to create peace, prosperity in a sustainable future for all families, communities, countries and regions just do better when women are educated, formally employed legally secure and politically well represented. Extensive empirical data from all over the world today informs and supports this thesis. Ordinary women are organizing to secure and advance their rights in every corner of the world today, and yet, a tiny fraction of public and private resources are available to support this work from the economic development area public health, human rights and soon humans security. Pieces of the foreign assistance, pots of money, despite all the evidence of the dispersion and impact and payoff, from giving grassroots women more money, we’re still not doing it adequately.

Ellen Chesler 02:30

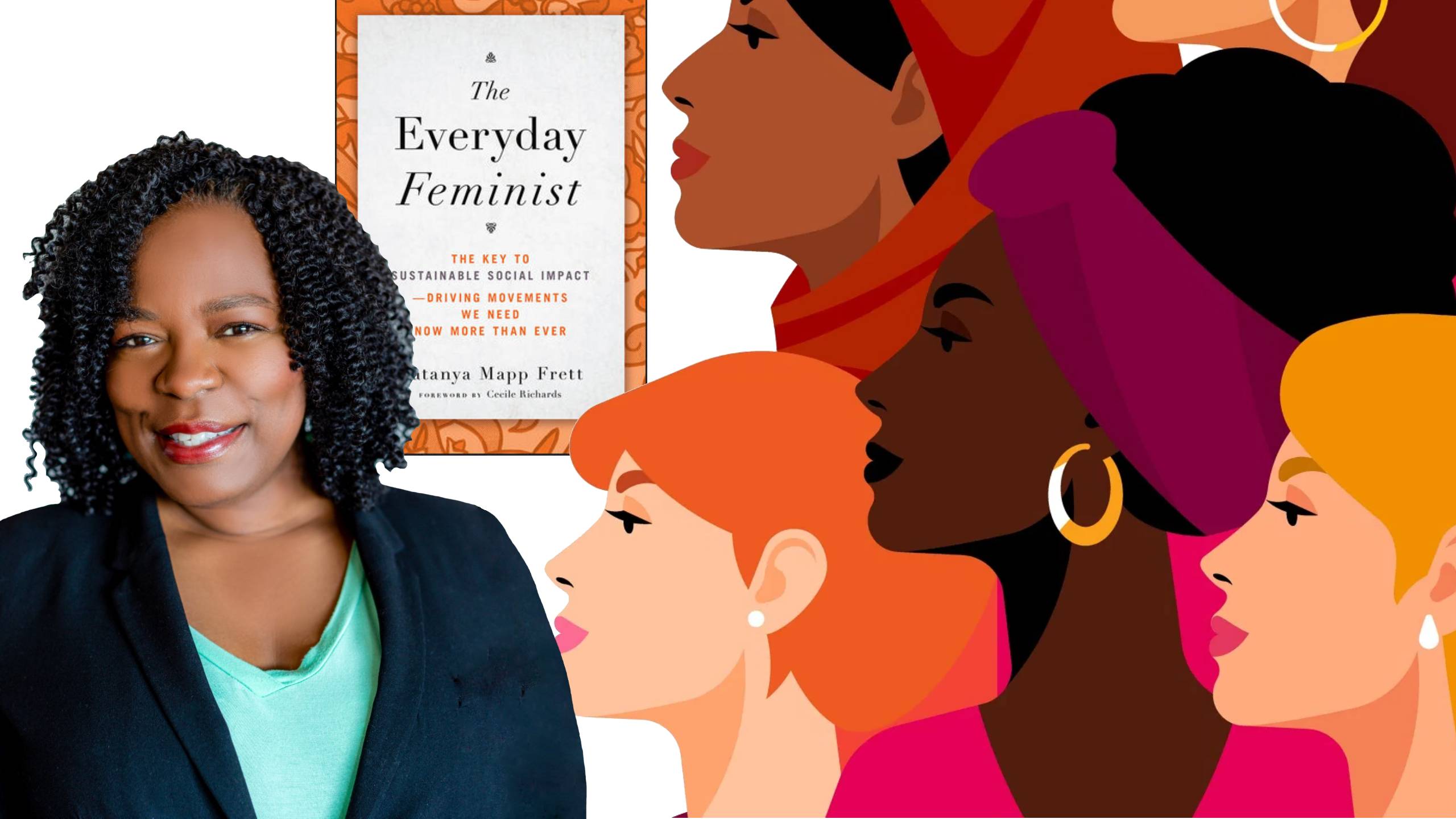

To talk about this dilemma and why we need to do so much better, we are fortunate to have a veteran of many years of work advancing women’s rights spanning 15 different countries, Latanya Mapp Frett, who is currently president of the Global Fund for Women and author of a compelling new book, The Everyday Feminists, The Key to Sustainable Social Impact Driving Movements We Need Now More than Ever, which was recently published by John Wiley and Sons. The Global Fund offers flexible feminist funding to help create meaningful, sustainable change. Since its founding, the San Francisco based group has put it over 5000 grassroots organizations in 175 countries. Trained as a lawyer, Latanya also teaches today at Mailman School of Public Health, for distinguished career has also included senior positions in Africa with USAID and UNICEF, and an executive position with Planned Parenthood’s Global Program, which is where we met. Welcome Latanya.

Latanya Mapp Frett 03:38

Thank you, Ellen, thank you so much.

Ellen Chesler 03:41

Let me begin by asking you to give us an overview of the book and what motivated you to write it. You have this compelling argument and supporting data, please pick out a few of the many captivating women you profiled in there and tell us their stories.

Latanya Mapp Frett 03:56

Sure. Thanks, Ellen, for doing this podcast with me. It’s always a pleasure to be in company with you again. And the book really is about how grassroots feminists are driving social change, and what we can all do to support them. And the book I tried to invite readers to explore not only the monumental impact of the everyday feminists, but the opportunities to champion and support them in their drive to usher in what for me, in the 30 years of my career, has been the most profound social impact we’ve seen in modern history. I mean, we can’t do this without them: We can’t pass the laws, we can’t get the resources, we can’t change minds and hearts, which is where we all know change begins.

Latanya Mapp Frett 04:40

And so everyday feminists represent their communities in these struggles for justice, equality, transformational social change, and you’re using their voice and other personal resources to get this done. So I talk about them as relatable and perfectly imperfect, in a way that makes them human. They’re not the once in a generation like lightning in a bottle charismatic leader. That’s not who we’re talking about. Rather, it’s these ordinary women with extraordinary passion that are committed to this work, and trying to not just to see sort of surface change, but really systemic large change happen. And they’re the ones who show up. I mean, they’re pushing forward, and they’re getting the hard stuff done. It’s not just a career for them, this is what they do every day, all day.

Latanya Mapp Frett 05:29

So the book has three parts. And the first part, I tried to really focus on sort of what is the social movement, why they’re being sort of overlooked and why it’s so difficult for people to trust and fund these women in their organizations. And then the second part of the book is really the stories like you said, I’ve lived in 15 countries, but I’ve worked in more than 50. And every country was different, but there were certain things that were the same. And these are the stories that you see in part two. And then [in] part three, I really tried to focus on why do we need everyday feminists and dig down a little bit on why they need us, and then conclude with some kind of like a checklist for different sectors on how we could do this better.

Latanya Mapp Frett 06:15

You said, I’ve worked with NGOs, I’ve worked at the UN with governments and foundations. And you know, this intention to advance gender justice and social equality around the world is something that we’re trying to do in every country. As you know, injustice anywhere is injustice everywhere. So this work can’t just be relegated to one part of the world; it has to really be intentional, and it has to happen everywhere where we find ourselves particularly in difficult circumstances.

Latanya Mapp Frett 06:15

And so the everyday feminist who have befriended me, who have taught me, and helped me learn and find my own power is what I talk about in the book. I spotlight a number of women, around eight women who many of us know like Tarana Burke and Loretta Ross, but some don’t. I mean, like the Minister of Mines in Nigeria. Some people don’t know Miriam Miranda, who is of the Garifuna people over in Honduras. So these are people who have been inspirations to me and have helped me and I wanted to highlight them in this book.

Ellen Chesler 06:55

Tell some of our listeners who Loretta Ross is, even though she just won a MacArthur Genius Award.

Latanya Mapp Frett 07:23

And she’s also–I mean for most of us that are close to her–she’s also the mother of the reproductive justice movement. Not just as a movement, but also as a framework. I met Loretta Ross at the Beijing Conference on women 28 years ago. Who is counting?

Ellen Chesler 07:55

She was then heading an organization were funded largely by the Ford Foundation program called Sister Song for reproductive justice from the bottom up.

Latanya Mapp Frett 08:10

Absolutely, and I tend to look at her and days on and others who are in that area in Atlanta, and look at black feminism in the work that they’ve done and continue to do, right, because they’re still at it, they’re still in it. And that’s the thing about everyday feminists is that they don’t let up. And now being in this position, at Global Fund for Women [with] the ability to also like sit on these boards like Oxfam and management sciences for help. I feel like my job is to remind people who these everyday feminists are, and why they need resources. And I do have a unique vantage point over the decades. And I know the value of the everyday feminist because I’ve spoken to them, I’ve sat with them, helped set strategy on their issues, and really just watched up close to the long term impact they’re having. And so Loretta is a classic example of how it doesn’t happen overnight. But these women are working at it, and they’re getting there; they they’re changing the game. They’re changing the names, and I think, what we need to be focused on if we want to see lasting change in our community.

Ellen Chesler 09:20

So tell us a little bit more about the Global Fund and how it works. How it figures out which grassroots organizer or group may succeed better than is worthy of investment. How does it choose its partners and evaluate its investments? What’s its annual budget? How does it raise money? I think people would love to know a little bit more about that.

Latanya Mapp Frett 09:44

Yeah, so Global Fund for Women started in 1987, with a few really, really simple thoughts in mind with three women, including of course, as you know, Ann and Francis and we’re about to celebrate…

Ellen Chesler 10:00

Anne and Francis, that I know, tell our listeners.

Latanya Mapp Frett 10:03

So Anne first Marie, and Francis… what’s Francis, last name? Do you remember? I’d have to look it up. But they were, as well as couple other women who were at the table, including Dame Nita Barrow, who a lot of people know from the Caribbean. She was from Barbados, and was president in that country at the time. So was very important politically. But they came together and their task was very simple. Can we give women money to do the work they’re doing? It wasn’t trying to silo them into a particular set of work, whether that was violence or HIV/AIDS, it was just, we trust women, and we want to get them money to do this work. I mean, a classic example that many people know, who know, Global Fund for Women is Leymah Gbowee, who’s a Nobel Peace Prize winner. And she’s featured (yes, from Liberia) and featured in the film, “Pray the Devil Back to Hell” that Disney did.

Ellen Chesler 11:08

She was a woman worked as many women do in countries in Africa in the market.

Latanya Mapp Frett 11:15

She needed to have an organization around her, which made her ineligible for almost all of philanthropy and government funding. But she came to the Global Fund for Women. And she asked for $10,000 to take some buses across the border from Liberia to Ghana, so that women could sit in at the peace processes, which at the time didn’t include any women at the table. But they took the liberty to take those buses, some food, of course, and they took a hundreds of women who stood and wouldn’t let those men out of that building until the peace accord in Liberia was signed.

Latanya Mapp Frett 11:55

And after that though, she built an organization around her and she’s still doing amazing things. She has her own foundation. But it was that kind of thing that the founders that Global Fund for Women were interested.

Ellen Chesler 12:10

Women made a difference in the ultimate resolution for Liberia…

Latanya Mapp Frett 12:14

Absolutely. If you remember she went through three civil wars in her lifetime, before she actually determined she just had to do something. And she talks about this story because she didn’t have a formal organization around her. She could not get funding from anywhere else. And that is the premise of Global Fund for Women.

Ellen Chesler 12:34

I would like to add to what you’ve just said about Leymah Gbowee is that the significance of what she [accomplished] did not stay limited to Liberia, although it had a profound influence on the outcome of the peace process in Liberia. But also it served as an example, for global policy to change, and the UN through something called Resolution 1325 of the UN Security Council now mandates the participation of women in peace processes.

Latanya Mapp Frett 13:11

Absolutely. And Global Fund for Women has been seeding these kinds of everyday feminists. And sometimes we get criticism, the saying, “oh, you know, if you’re only focused on feminists or you only focus on women, and women’s efforts.” And it’s like, so not true, because what Leymah Gbowee was doing was not just for women. I mean, she leveraged women, and everyday market women, to work on these issues. But what she was looking for, was completely for everybody; it’s for the entire society. And you’ll find that most of the women that I talked about in the book, it is not just women’s issues; it’s more than that. It is a society that we all want; a future that we all want. And that’s why I say it’s so important for us to continue to lift them up and to stop undervaluing what they can do

Ellen Chesler 14:07

Well, and that the key to poverty eradication and no growth of economic growth of countries cannot come top down as it did, as well as the view of so many investors in development in Africa for so many years. You know, if you built the idea was World Bank would go into build infrastructure thinking that that somehow would help eradicate poverty. But what it did is it made a few people very wealthy and did not address the fundamental issues in the society, and certainly did not address poverty because so many of the women do the major work in agriculture and trade in Africa. We’re not the beneficiaries of any of these investments and that I think is what’s changed or is changing. And there’s so much better understanding today of what inclusive development really means. Inclusive development means getting resources to women, as well as men. Two kinds of considerations of intersectionality to have to be part of the funding process. If you are going to bring about meaningful, absolutely, and change. Let’s talk about the current campaign that your book engages with of the Global Fund. It’s called the 1.9 campaign. Let’s tell our listeners what that means and what you’re trying to accomplish here.

Latanya Mapp Frett 15:49

Absolutely. Thanks, Ellen. So in the book, actually, we talk about this the amount of funding that gets to grassroots women’s organizations, and we talk about it as a part of the overall OECD numbers that come out each year. So when this book was written, the overall number of money that got to–particularly global south countries from the global north–that amount of money for grassroots women’s group was about 1.6%. So since the book, another round of research and data has come out, and it’s 1.9%.

Latanya Mapp Frett 16:26

So Global Fund for Women, has a campaign going called “1.9 and rising”. And our goal is to get people want to understand that that number, because sometimes people hear it, and it just sounds so drastically low. They’re like, “it can’t be true.” But it is, and we’ve been tracking this number over time.

Latanya Mapp Frett 16:43

And I gotta say, Ellen, the overall number of actual money that’s going towards gender equality is falling. So it’s not increasing as it had been for years. And so when you talk about this number, this 1%, or 1.9, that is, what’s the percentage of gender equality money that’s actually getting to community based organizations run by women. And so it is extremely low. And we’ve got to get that number up. So our goal is to talk about this number with the broader public, and we even want to do some work on the hill with that, but then also trying to get that number up, you know, increase the level of funding that gets to grassroots women. It’s already such a small pool. And we need to sort of think hard about how we resource, what actually works.

Ellen Chesler 17:39

Again, I think, where do you think the money goes? And why is it being spent wrong? So much development assistance from the North, or in the West, however you want to identify geographically winds up going to organizations based here rather than based in the countries?

Latanya Mapp Frett 18:04

Oh, absolutely. And it’s not unique to the US at all, I would say and Carnegie did some work on this.

Ellen Chesler 18:12

Carnegie Corporation, the foundation.

Latanya Mapp Frett 18:14

The foundation, I’m sorry, yes. And they looked at what percentage of in in most countries in the Global North that have foreign assistance dollars that go into Global South countries, I think the number was around 70, close to 70% of it stays in the country. Like organizations like the “beltway bandits,” we call it. So those organizations like the key money. Even Management Sciences for Health is one.

Latanya Mapp Frett 18:43

So they have these large contracts, where technical assistance is brought in the country, where the money is coming from, and then that’s how it goes out in the UK. It’s like many and Daniel’s. So these are for profit.

Ellen Chesler 18:58

And again, in the era before the internet before, good communications, it was necessary to (in theory) to protect the funds and also be diverted by often problems of corruption in developing world countries, that sort of thing. I don’t think people were malevolent completely, they may have been misguided, but they weren’t malevolent.

Latanya Mapp Frett 19:23

Not at all. And there is still a place, Ellen, for this kind of support to countries. This kind of support, like for health systems in particular country in Rwanda. There is still a place for that. What we’re saying though, is the changing narrative, the social change issues have to start in the countries. That’s where movements start, they start where the where the injustice is, and there has to be more support that goes to these organizations that are developing a what is quite frankly, movements on their own and these countries, but without the ability to actually get any kind of resources, when we have to think about to this aligned with a lot of countries are starting to close their civil space. So that means women’s organizations that have been doing this work for, if not centuries, [for] decades, at least, are now suffering from sort of the bureaucracy of closing civil spaces in democracy shrinking for them in their countries.

Ellen Chesler 20:26

It’s becoming more autocratic. And yeah, that’s a part of civil society. Right. So, not only emphasize what’s going wrong, though, I feel as though sometimes we tend because the problems are so overwhelming to focus on the problem and not on some solutions. I was lucky enough to be at the Council on Foreign Relations recently, where Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada, in response to a question from the audience spoke of Canada’s new feminist foreign assistance policies added to not just 1.9%, but to making sure that 15% of Canada’s bilateral international development assistance across all sections and categories would go to advancing gender equality.

Ellen Chesler 21:26

And in other words, that meant health, economic development, democracy building or political participation. And he committed, he says, the country has committed $150 million over five years to grant to support local women’s organizations in recipient countries. This is not something Canada invented. This idea of a feminist foreign policy, or a feminist development assistance program actually started in Scandinavia. And in Sweden, changes in governments there, as you were saying, are threatening some of the tradition that has been built to do this kind of assistance, because more conservative governments are in some instances, standing back, and changing, demanding changes in these laws. But can you say anything about Canada and other countries? Or the possibility of real change?

Latanya Mapp Frett 22:45

Well, and there’s, like you said, there’s a number of countries that, you know, some of them calling themselves having a feminist foreign policy. And what Canada did was actually quite unique. And many people don’t know that that feminist foreign policy, and the ultimate policy that came out of that around foreign assistance, was very much an advocate advocacy work that Global Fund for Women did, along with Match, which was the Women’s Fund that was based in Canada. And Match is now a part of what is a partnership between the Women’s Fund and the Government of Canada, and it’s called the Equality Fund.

Latanya Mapp Frett 23:22

And did they invest 150 from the Canadian government itself, but other donors also put money into that pot. So a total of $300 million, is put into an investment that specifically looking at either women owned businesses, or businesses that have a significant interest in women advancement and have women on their board. So it is a private sector equity fund that then the Women’s Fund can use the proceeds from that in order to give grants. And it’s actually built a lifetime. The government hasn’t just said this year, “we’re gonna give you this much.” They said for the foreseeable future, we want to make sure that women and other countries have access to funding that will allow them to do the work that they do.

Latanya Mapp Frett 24:16

And this is new, Ellen, so we’re talking about a feminist foreign policy that is brave, that has really gone beyond what almost any country has done, including the Scandinavian countries. Now, we do have a partnership with Sweden, and that’s where you’re talking about, you know, more conservative government has come in now and said that they’re no longer a feminist foreign policy country, but we still do have a really good relationship with them. And, you know, as you know, leaders can’t break up everything that has been happening and the move towards supporting gender equality at a much higher rate. It has really already been, I think, embedded into the hearts and minds of the people.

Ellen Chesler 25:00

That’s very heartening to hear. Yes, but it does suggest to our listeners how important leadership is in the developed world as well, as we need to make sure that we continue to elect progressive representation here, committed to these issues. Although, interestingly, I’m always trying to be realistic as possible. In my advanced age now, having done this work for almost a century, one of the best examples of a good a foreign assistance program that does actually invest in women in the United States and does invest bilaterally and doesn’t deals directly with recipient countries is PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief, which was actually started in the Bush years. GW Bush had an extraordinary legacy and is now a model, I think, for other foreign assistance programs.

Ellen Chesler 26:10

Again, the Center for Global Development recently had Samantha Power, the new head of USAID, an interview, which I listened to online. And that, too, gave me a little bit of hope, because Samantha, representing Biden Administration, obviously, is quite committed to changing the way American foreign assistance is dispersed to doing much more bilaterally directly with organizations in countries building public sector capacity in countries as well as civil capacity and countries, among groups, like women’s groups, but we need to, in USAID down much more than we’ve done in the past. To make sure that…

Latanya Mapp Frett 26:57

Yeah, I think that’s right. And I would say, because, you know, I’ve lived in the belly of the beast during these days, and for lack of a better term, and I was responsible for implementation of the PEPFAR program. And I think the intention was absolutely very well documented. And the impact of it was well documented, I do think that some of the things that we have to remember, as you mentioned earlier, is the intersectionality. Of these issues, PEPFAR was very siloed. So in the countries where I served and worked, you would have a sort of growing and developing public health system of which then PEPFAR sort of would only exist in parallel that they were not allowed to use, for instance, they couldn’t mix it with reproductive health, which, as we know, I mean, STDs and you know, women’s health and reproductive health are all connected.

Latanya Mapp Frett 27:55

And so to not have that connection and the health systems, it really did mean that the program sort of existed on its own. And it didn’t respond to the intersectionality of women, who were living very, very multiple, sort of affected lives. And for them to have to go to one clinic, let’s just say, or hospital for a certain type of care, and then to another one for HIV. And so I think what we’re learning though, what we’re seeing, Ellen, is that people understand that we can’t go in and just build projects that are isolated from the lives of the people that they’re trying to impact and that very much so and I’ve seen this in Management Sciences for health, of course, the understanding that it has to be an intersectional approach to understanding that you have to work with it with what’s already on the ground, and not to build new structures, and programs that are outside of the programs that are in the country.

Latanya Mapp Frett 28:51

So I do believe we have learned a lot over the last couple of decades, and we’re moving in the right direction. But I do also work with USAID, I retired from there. So I understand the bureaucracy that goes in trying to do direct grants to local organizations. And I think they’re trying to balance the extensive bureaucracy that used to working with organizations that are very large, multimillion dollars with this, juxtaposing it with these very small grants that goes to communities. So I don’t want us to pretend that you know, the sort of framework of a bilateral having a relationship with a very local organization, nor do I want us to pretend that that might not be dangerous for the organization who’s doing some of this work particularly around racial justice, gender justice, immigration justice, so all of these issues that are you know, plaguing a lot of us have to have a very different approach. You have to have a unique approach. These groups can’t be expected to deliver the type of even just something simple as reporting that is required from most USA grantees. So if we’re going to do more, we have to also remember the sort of…

Ellen Chesler 30:12

Strange.

Latanya Mapp Frett 30:13

Yes, exactly.

Ellen Chesler 30:15

What I’ve always admired about you, Latanya is because you were a practitioner in the field, both working for the UN at UNICEF and for USAID, you’re not, you’ve certainly remained an idealist, but you aren’t impractical. You understand how difficult it is to make the implementation of these programs in a way that makes them effective and also protects the investments. But I think you more than anyone are, your perspective is important, because you have such a broad vision of how to deliver aid effectively. And you understand that the payoff from aid that reaches women’s civil society just tends to be greater; there’s less waste, there’s more impact on communities. The famous saying give a woman and she’ll feed her family, provide for her community, secure her country and change the world. And I think one doesn’t have to be essentialist. This isn’t not a biological thing. But the social structure of countries is built around women’s work, and not only in a family, but also in the both formal economy more and more, and in the informal sector in so many of these countries. And so, empowering women, giving them reproductive health care, protection against violence, political representation, more secure legal provisions. This just pays off in very big ways.

Latanya Mapp Frett 32:04

Yeah, and I was just gonna say, and I think that there has been a growing body of data and evidence that proves exactly what you were just saying around this logic model. But where we are politically in the world can sometimes make you think that we’re still struggling, or swimming upstream to actually implement what we know to be fact. And so that is what I think for me, the book, and Global Fund for Women in partnership are trying to sort of make this case and tell stories to help people. So help people like staffers on the Hill understand why is it important to have feminist funding. Why is it important for feminist movements to succeed. And so this case, we want to make this strong case, so that even those that are sort of somewhat on the fence, they know that gender equality is the right thing to do, but not so convinced to put more funding and other resources in it. We’re hoping that this can help tell the story and show that women’s funds have been doing this for decades now. And we have seen the impact, whether it’s around ending civil wars, like Leymah, or getting female presidents elected and securing laws that give new protections to millions of people. It is documented, it is working, we just have to now invest more in getting those outcomes.

Ellen Chesler 33:34

And also really enforce the interdependence of human rights and development programs. You know, you can’t have development without rights you can’t embrace without development; that’s kind of the fundamental mission of the United Nations. But it was sort of aspirational. It’s now becoming a little bit more important.

Ellen Chesler 34:05

Let me just use the little bit of time we have left. Since a lot of students listened to these podcasts on younger people beginning their careers to ask you to talk a little bit about your own life journey, which is so compelling. Can you in specific detail, tell us a little bit more about how you got into this work? What was your educational background? You know, how did you get to Africa? How did you get all these things?

Latanya Mapp Frett 34:38

Yeah. So I mean my parents will say that I knew I was going to be a lawyer from the time I was five. And lucky enough growing up as an inner city Black girl in Philadelphia, sort of lower middle class you know, but still considered myself incredibly privileged. You’ve seen injustice, right. You live it, you live it every day; my brother was in and out of the juvenile justice systems. In my home, there was abuse of my mother. And so later in college, the first thing I remember was marching. Literally that first semester was around apartheid and getting University of Maryland to divest. And so that you just start breathing this work to to seek a quality in your settings.

Latanya Mapp Frett 35:26

And so I knew I was going to law school. And I got into a program that actually helped me see. It was in Kenya. It was in the law faculty at University of Nairobi with Widener Law School together had a program on what they call International Public Law. And there was a certification program that really just taught you about all the systems that you were talking about our international multilateral structures, and how you can use them as a lawyer to make change and, and very heavy on the human rights side. And that’s what got me into, I went into Peace Corps.

Latanya Mapp Frett 36:04

I started working with the UN as a human rights officer, and more specifically with child protection and gender equality when I was at UNICEF. And that kind of got me started on the road that I eventually took, which more and more and some of the stories in the book, talk about. Each experience kind of helps you learn what was important and how you go about this work that we call development. So when I was with UNICEF, I decided to move to the US Foreign Service. Because there I kind of felt like I needed to be on the home team. I know that kind of sounds crazy, but it’s like I was doing it all over the world. But understanding that the US has a particular place of power and privilege and funding. We talk about this with the global gag rule. We know that what the US does affects other countries in a huge way. And so I thought my perch would be the Foreign Service. And I did that.

Latanya Mapp Frett 37:06

But then it was when I met Cecile Richards, who many of you know from Planned Parenthood, as she talked to me about their international program, I applied immediately. It was that passion. It was that same passion that led me to know that I’m really focusing on an issue that I didn’t have to be agnostic about, right. I could have a side, you know, with the US government, of course, in the Foreign Service, it’s really hard to have a side. You have to you have to go with the political swings of the day. And so that experience with Planned Parenthood was so profound, because it was, I can actually advocate for the side I want it to be on.

Ellen Chesler 37:49

Are you telling our listeners that not all of, I don’t know if you’ve watched it yet, but it’s absolutely preposterous, but absolutely, totally wonderful, this new Netflix series called The Diplomat, where, needless to say, the career Foreign Service officer takes sides in a way that rarely happens, but…

Latanya Mapp Frett 38:08

Rarely, yes, that’s right. But it’s there. Of course, we have incredible Foreign Service officers who now more and more are becoming ambassadors like in the show. Career ambassadors used to be rare. But I think since the Obama times they’ve become again, I know you’re looking at what Biden has done, it has been pretty incredible the number of career ambassadors that are…

Ellen Chesler 38:32

Particually in the developing world, more and more of our career Foreign Service is akin to Europe’s in other parts of the world, where people who really are specialists are in charge of these missions. And it’s really important, I think.

Ellen Chesler 38:52

I don’t have time, but I don’t want to end without asking you to sort of tell us after this long and brilliant career, in so many different important institutions and countries, what causes you the most despair, what gives you hope for the future? I like to say that way back in the 90s, the Cold War had ended, the United Nations was addressing a human rights and development in a much larger and I think, more hopeful national security framework, or global security framework. But in the years since regional wars, refugee flows, that climate crisis, HIV/AIDS, and more even more recently a global epidemic, diverted resources that we never fought way back in the 90s. We just didn’t see any of the those on the horizon. So, so many of the hopes and aspirations we had and were – take, like Beijing, or you and I both were lucky to be, although I didn’t meet you there – have sort of been torn asunder by these many global demands on resources. What gives you hope? What gives you what cost?

Latanya Mapp Frett 39:05

So Ellen, I’m just convinced that social change is possible. And I think you got to start there, right. And I think with the possibility of social change, which brings with it, the economic and political change, of course, there is this possibility for accountability. There’s this possibility for change for better in our societies. And I think I will just end by saying, and I wrote this in the book, that a major lesson for me in listening to and working with everyday feminists and action is that we have to get out of the way of young feminist leaders.

Latanya Mapp Frett 40:54

I am so stunned – and now I have my daughter, my second child is going off to college now – and I am in awe, particularly of adolescent girls are how they’re driving today’s social justice movements. I know, we tend to focus on how much they’re on their phones, and you know, all these things that they care about, that maybe don’t seem important to us, but their intentions to build a more just and equitable world for everyone gives me hope. And in recognition of this, and in line with the commitment to intergenerational feminism, we must just lift and support their work in real terms. So I’m excited about that. And I think we can do more than just put them on a stage and have them do our social media feeds, I think we should give them the startup resources to fly on their own.

Ellen Chesler 41:49

To really invest in youth as well as women. And girls. I couldn’t agree more. I think they’ve come of age and a different set of circumstances. The end of the Cold War and their perspectives are most important. So I guess we have to end because time is out.

Ellen Chesler 42:09

I want to thank today’s guest for the episode, Latanya, a pleasure to spend time with you and to hear your many insights about the role of women and sustainable development and making democracies work. I hope our audience enjoyed the conversation and we’ll look for your new book The Everyday Feminist.

Ellen Chesler 42:33

Please remember to rate and subscribe, just subscribe to and even rate international horizons on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you’re hearing this podcast. My thanks to Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance, as well as to Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for the show. My name is Ellen Chester, and I want to thank all of you for joining us. And I hope you can we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.