Where is the Left? The rise and decline of social democratic movements

Populism, nationalism, and ethnic and religious chauvinism stalk the global landscape; culture wars pervade the political scene; and democracy stagnates, erodes, or is on the ropes at the hands of would-be strongmen the world over. How did we arrive at this historical path? What is the relationship between the deterioration of social democracy and the rise of authoritarianism? What role does immigration play in promoting and unsettling social democratic welfare states?

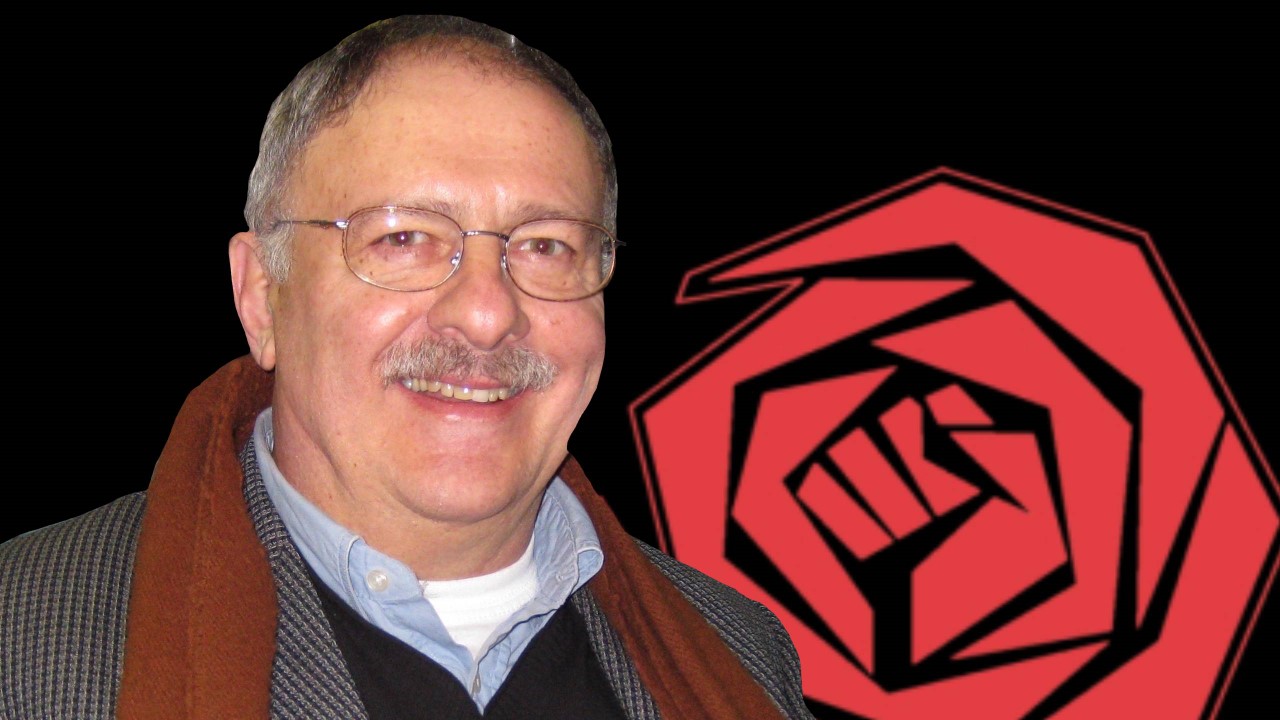

This week on International Horizons, David Abraham from the University of Miami discusses the origins of social democratic parties in Europe and the parallels with similar movements in the US. Following his teacher Adam Przeworski, Abraham argues that Keynesianism boosted social democracy by convincing people that the state could manage economic growth. For a time, the iron curtain heightened solidarity in the West, including among social democrats. More recently, social democratic politics has been tempered by liberal movements focusing on “diversity” rather than on class inequality. While noting that there are troublesome signs of growing authoritarianism around the world, Abraham argues that the Trump movement is not comparable with historical fascism.

Transcript:

John Torpey 00:46

Populism, nationalism, and ethnic and religious chauvinism stalk the global landscape; culture wars pervade the political scene; and democracy stagnates, erodes, or is on the ropes at the hands of would-be strongmen the world over. How did we arrive at this historical path? What is the relationship between the deterioration of social democracy and the rise of authoritarianism? What role does immigration play in promoting and unsettling social democratic welfare states? Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues.

John Torpey 01:34

My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. We are fortunate to have with us today David Abraham, professor emeritus of law at the University of Miami and, earlier in his career, a historian of 20th century Europe at Princeton. He is the author of the recent Wer gehört zu Uns? Who Belongs to ‘Us’? Immigration, Integration, and Solidarity in the Welfare State. His first book, The Collapse of the Weimar Republic, examines the effort in interwar Germany to create a social-democratic welfare state. He is currently — or at least will soon again be — a visiting scholar at the Advanced Research Collaborative of the CUNY Graduate Center. Thanks for being with us today, David Abraham.

David Abraham 02:29

My pleasure.

John Torpey 02:30

Great to have you. So since it seems to me that the concept of social democracy that is so central to your work may not be as familiar to listeners as it once was, maybe we could start by having you say a little bit about the meaning and history of that term.

David Abraham 02:47

Certainly, the first thing I would say it’s ironic that we’ve reached the point where the social democratic form of governance seems to be a thing lying so far behind us; that we need to remind ourselves of what it consisted because it was, in fact, the primary form of governance in Western Europe, US and other countries [such as] Canada, Australia, elsewhere. And it now has been succeeded by that constellation that we call neoliberalism. Social democracy enjoyed a long history, beginning with the labor and socialist movements of the mid and late 19th century, a movement that was initially committed to overturning the capitalist order and replacing it with something Marxist or socialist if not Marxist. [In addition to] moving power, both economic and political powers, to the masses, primarily, the working class, which it was assumed would become the demographic majority as well as the premier political power.

David Abraham 04:09

As a demographic matter, the working class never became an absolute majority of society, except for one place in one census, in the 1910 Luxembourg census. Those that could be concretely identified as working class were a small absolute majority, but never before and never since and nowhere else has that been the case. This became a crucial fact because it meant that the working class movement, the socialist parties, their affiliated trade unions, had to reach out to other social classes in order to obtain majorities in electoral or democratic or quasi democratic political systems. Thus the socialists, social democrats before World War II never succeeded in accomplishing in a stable way.

David Abraham 05:07

There were moments like the Popular Front in France, a few years in Weimar Germany, where social democrats really headed states, headed governments, led economic and cultural programs. The real successes of social democracy — and here I follow the analysis of my old teacher, Adam Przeworski, who probably laid this out more effectively than anyone else — owes a very large debt to Keynes and to Keynesian economics. Why? Because this enabled social democrats to create a structure based on growth and legitimating government intervention and keeping the economy rolling smoothly and flattening out recessions and the like. So social democracy came to represent not only the reallocation of sort of resources within society, but to — in the famous metaphor — growing the pie instead of fighting over where the slices would be exactly.

David Abraham 06:25

So although social democracy never gave up the redistributive effort, it also became centrally implicated in economic expansion. Something which in recent years, we’ve seen critiques of from the green position [and] from the green left. So, social democracy really came into power; not directly into power, but became the dominant force in Europe, I would say in Germany, after abandoning in 1959 revolutionary Marxism. Similar developments and France with the isolation of the communists from the socialists, and in Scandinavia above all, in an ongoing way. So the social democratic form of governance relies on coalitions of working class people, organized and educated through their trade unions, along with allies following the path of enlightenment, which is to say, liberal middle class folks.

David Abraham 07:40

We’ve seen in the United States a kind of diluted version of this in the Democratic Party, its apogee being the New Deal, where again [we had] unionization levels, where higher working classes almost automatically voted for Democrats or Social Democrats. And they were joined by some elements of the clerical classes, mall owners, educated people, etc. When exactly? Well, let’s take a moment to recount the accomplishments of the social democratic era. One can measure it’s been 60 years long, ending either with the oil shocks of 1973, or the rise of Thatcher and Reagan in the 80s. But in most of the years preceding that, and to a certain extent, still in an inertial process. And the years since that, the social democratic era vastly reduced inequality, poverty, expanded education, expanded higher education and expanded medical care, [which] created what in the United States came to be called the middle-class working class people, living a middle class lifestyle with homeownership and certain measure of savings and various forms of insurance, unemployment, insurance, and other such things.

David Abraham 09:15

All of this is part of the social democratic inheritance. That project, of course, had its costs and its exclusions and maybe we can say a couple of words about each of those. Among the costs was the ruthless exploitation of nature, in the name of science and progress. That is something which as we know in the last 15 – 20 years has come under a lot of criticism, but social democracy was productivist. Mass production, mass commodities, cheaper, belief in science, belief in technology. Progress in short. And that has a cost in nature. Although we didn’t think of it so much at the time, it’s become very clear to us since that bordered states were critical to this.

David Abraham 10:14

The notion that “I am my brother’s keeper” came to be more widespread with the growth of a liberal, enlightened ideology that was very much against discrimination. It had trouble with gender and women’s role in the economy. But maybe we can come back to that. But it was certainly based on the idea of America, of the abundance republic, of France. In other words, nation states that had very low rates of immigration in these years, which was in part due to the so-called Iron Curtain that was in part due to that, then much higher cost of communication and transportation and the non availability of technologies of simultaneity, like the iPhone. So, countries were more encapsulated, culturally and politically. This enabled — this is one of the ironies — a growth of solidarity feeling, a civic nationalism; “we’re all Americans,” apple pie, hot dog, Chevrolet, or in the more sophisticated version: we’re all followers of the Habermas notion that we have a civic nationalism, we adhere to the same constitution, we share the rules of public political discourse, and civility, we have diverse ideas, but we discuss them together and rationally.

David Abraham 12:01

All of these mechanisms presupposed a certain measure of homogeneity. And what we used to call the United States consensus, which did narrow, it’s true. To have the system function stably, you have to get rid of Nazis in the case of Germany. You have to get them out of the public sphere, which was a slow process, but which was effectively accomplished. You have to marginalize communists or others who are still calling for revolution, which was also done. Or they themselves became players, as with the Italian Communist Party, for example, Spanish Communist Party divorced themselves from the Soviet Union and certainly from China, and began to be Euro-communist, which meant essentially that they were more radical social democrats.

John Torpey 13:07

Right. So this has been a very valuable kind of overview of social democracy for the last 150 years, really. But you started to raise some issues that I wanted to ask about a little bit to get you to say a little bit more about. One of them in particular is the issue of immigration, the immigration and social solidarity. It may be worth noting that the United States’ sort of surge towards a social democracy had to do a lot, as you’ve already said, with the New Deal. And that that took place during a time when there was effectively no legal immigration into the United States. Do you see those things as connected? The United States has long been seen as a place by socialists, as a place that’s driven in certain ways, by ethnic, religious, other kinds of difference, which have undermined working class solidarity. So, how do you see these things as being connected? This is, in effect, what your most recent book is about, so maybe you can talk about that?

David Abraham 14:16

Absolutely. So let me say two things. First, Werner Sombart, the German sociologist of mixed reputation, but nevertheless, an astute observer, tried to answer the question: why is there no socialism in the United States? Now, one might say that the question is mal posé, but when he posted around the turn of the last century, it did seem to be the case at least, that the United States didn’t have anything like a European socialist movement.

David Abraham 14:52

People who liked that talk about American exceptionalism, but his argument was that there was no strong socialist movement in the United States, because there had been no feudalism, so there’s no nobility to throw rotten tomatoes at slavery and racial conflict. Well, he never used terms like, racial capitalism or white privilege, but certainly he suggested that racism divided workers in the United States and undermined solidarity. And the third thing was high levels of immigration, which at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, were indeed very high. In fact, the largest share of the US population to be foreign born was around 1912, as I recall, on a figure that we only reproached in the last three or four years here in the US. And then if we turn to Europe, it’s an unhappy thing for liberals.

David Abraham 16:07

And it must be noted that most social democrats are also liberals, in the sense of a larger philosophy of life. And the countries in Europe with the strongest social welfare systems have been those that were and are still most ethnically homogenous. Scandinavia is the most obvious example, Austria another. Solidarity and diversity have a difficult time thriving together. So in those years, again, partly because of the Iron Curtain, partly because of the difficulties of transportation and communication — the 1950s, 60s, 70s, 80s, I would say even — saw more and more calls for economic redistribution amongst populations, which because of the advances of anti discrimination principles, were more uniform. In the case of Scandinavia, they were also ethnically very uniform. And in the case of countries that were coming to see more diversity like Germany, it was a very limited diversity, and was focused on political and legal equality more than on cultural recognition.

David Abraham 17:19

So the shift, which parallels the growth of migration, — which Nancy Fraser and others have discussed — from politics of redistribution to a politics of recognition, of welcoming, or acknowledging if not welcoming, the growth of a migrant population, an immigrant population with initially different values, different looks, different religions, etc. Fairness, liberal principles require the acceptance of difference. We see this now in the United States, this is a major central theme, perhaps even of liberal progressive politics in the United States. Now, this is not a zero sum game, but there is a troublesome negative correlation between solidarity and diversity.

John Torpey 19:00

So you talked in your kind of overview of the past of social democracy about the fact that the working class never really became a demographic majority. And one question that arose in the course, especially of the 20th century development and 20th century history, was whether there weren’t a bunch of working class people who were now wearing white collars. So there was this whole question about the white collar, the new working class, the new class had various kinds of designations over the period. And, it strikes me as though there’s obviously a differentiation in what was thought, at least potentially, to be the sort of social base of a socialist movement. And the introduction of white collar workers who are increasingly of course distinguished by their education also means that they are sort of functionally differentiated from what we traditionally thought of as the working class, the kind of industrial working or productive working class. And nowadays, people like Thomas Piketty are arguing that the real divide in societies is between essentially working class people (of the old style blue collar), less educated people and more educated people. And this distinction between liberal and social democratic, I think to you is sort of self-evident, but I think in the United States, because we associate liberal with left in a way that isn’t necessarily the case in Europe, these things kind of have a certain parallel track. The introduction of these populations, more educated population groups and ideas of liberal and social democratic sort of get mixed up and confused, I think, in certain ways. And so maybe you could speak to what’s been going on in that regard.

David Abraham 21:06

There are a number of distinctions that you’ve just raised, let’s try to do at least a little justice to each of them. And it’s certainly true at the cultural level that working class people have never been avant-gardists, whether the question is abortion or religion generally, or gender identity to name some contemporary questions, or modern art to name some older ones. Working class people are not — by virtue perhaps — have less cultural exposure, less education — in the form of progressive cultural politics. Now as to who the working class is, a lot of ink has been spilled on this. Of course, it is true that many blue collars have turned into pink collars, many blue collars have turned into white collars. And many blue collars have turned into polo shirts.

David Abraham 22:06

So there’s no question that the image of the lunchbox carrying miner or steel worker does not describe the contemporary labor market, let alone the contemporary population. So many socialists hoped and scholars hoped, nevertheless, to demonstrate the existence of a working class majority in society have tried to deal with this. Eric Olin Wright, late Eric Olin Wright from University of Wisconsin-Madison probably devoted more energy and ink to this than almost anyone else and got as good a job as anyone could. And describing how in terms of incomes, lifestyles, education, voting patterns, and it remains true by the way that lower income level people do in the United States and in Europe vote more to the left than higher income people, which remains a true fact. But what [research] work, like [that of] Eric Olin Wright, have not been able to overcome or not been able to bring into harmony is the old distinction, the very old distinction between a class in itself that is to say a sociological category and the class for itself a political category.

David Abraham 23:39

So why working class people, whether defined by the color of their collar or their income, have not produced coherent politics — as the industrial economy has transformed into a post industrial economy – may have a lot to do with party structures, leadership, cultural transformations, etc. So I can’t answer that question effectively. We know that recent efforts to do that, whether [the left] alliance in Germany, or Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece, have not have not been successful. And we see in the United States that the most progressive segment of the Democratic Party, whether it’s Bernie Sanders or AOC, or Ro Khanna to shift from east coast to west. That very tenuous connection between Piketty’s educated liberal enlightened Brahmins, as he calls them, or us, and core working class people. This is Bernie Sanders central project. And it’s the project of new journalists today, like Jacobin, to create this kind of demographic and political constellation of working class people in the classical sense, and enlightened liberals. And one way to try to do that is to get away from these educated cultural issues. But there are people who care more about their pronouns than about the distribution of wealth in the United States. And that’s a tough coalition to build.

John Torpey 23:39

Indeed. So this in a way brings us to the next question I wanted to ask, which really gets back to your earlier work, which had to do with the creation of a social democratic welfare state in interwar Europe and in Germany in particular. And it turns out that the book is being reissued after its first publication 40 years ago; few scholars have that kind of distinction. So I want to congratulate you of course on that, and ask you what is it about a book that had to do with the collapse of the Weimar Republic, a kind of liberal, progressive foray of the Germans into the modern world that soon collapsed and led, of course, to the Nazi catastrophe? Why is a book like that of interest to people? Obviously, it says something about the context in which we now find ourselves. So what do you make of that?

David Abraham 26:57

Well, the word fascism is much in use these days, and whether it’s January 6th in the United States — and what some people call the Trump’s Beer Hall Putsch, his first effort as seizure of power — or the general rise of right wing populism in places like Hungary, Poland, elsewhere, India, Israel, you can create a very long list depending on what you think the core indices of fascism might be. But the fact of the matter is, not only as a hegemonic social democratic constellation, not only is that in the rearview mirror, but the neoliberal period that followed it. And here, I think the United States is perhaps the best example.

David Abraham 27:56

And the Republican Party discovered that in a democratic, or putatively democratic political system, you cannot win elections with McCains and Romneys and Bain Capital and more and more tax cuts, and more and more upward redistribution and privatization. That will not win the election. And what wins elections, it turns out, for them is the Trumpian populism, which is a devil’s brew of protectionism, autarky on paper not in practice. Protectionism and autarky and deindustrialization combined with racism and belligerence toward liberal cultural values, something which Governor DeSantis is now refining far beyond Trump’s capacity to do so. So what the Republicans discovered is that the mass base for neoliberalism is not what it was in the days of Reagan, when in a Cold War context and — even if declining — sound manufacturing sector, you could say things like, “get government off your back,” à la Reagan. Trump wouldn’t say that. Trump would say the government’s on the side of the wrong people. We got to get around the side of the right people. And you combine that with what are in fact, conservative economic policies, tax cuts for the rich, the deregulation, not only in the environmental sector, [but also] in the labor sector everywhere. Those are the standard conservative Republican policies but with a populist sales pitch. And that also resembles Weimar Germany; the Conservative Party kept shrinking through the 20s, and they could not win electoral majorities. And they thought a coalition with this lower middle class party, the Nazi Party, would bring them to power. And it did, only it didn’t take long for them to discover that they had surrendered the right to rule in exchange for the right to keep making money.

David Abraham 30:30

Now, what’s different in the United States today is the place of the American capital when there is no threat from the left, right? There’s certainly no Communist Party. You can say that a quarter maybe of the Democratic Party is a Social Democratic Party. The rest is a party of Wall Street and Hollywood and not a party of the working class whatsoever. So with maybe a quarter of the Democratic Party is a social democratic challenger, no Communist Party, a military dominance around the world, the American economic elites aren’t interested in fascism. Here, I differ with people like Timothy Snyder, who think that, you know, Trump is just a Nazi wannabe, or a Mussolini wannabe. I don’t see it. Folks in Italy, where the inheritors of the Fascist Party have never disappeared, they may have more reason to be concerned about this, partly because of the instability — and Italy being famous where governments that don’t have much of a halflife over the years, and where under different names of fascist parties have never completely disappeared — may have more reason to be concerned. But even there, I think, so much power in Europe resides in Brussels and the European Union and the European Central Bank, and Frankfurt. We saw that what got rid of Berlusconi, in the end was not any kind of left liberal upsurge in the Italian electorate, but the decision after the economic crisis of 2008-9 that Berlusconi had to go. So it was ultimately Brussels and Frankfurt that got rid of Berlusconi. So I think what’s missing today from the fascist brew is an interest of the economic elites and having fascist government, they don’t need to have it.

John Torpey 32:43

So Orban is a is an authoritarian but not a fascist.

David Abraham 32:47

Yes, I think Orban is a right-wing authoritarian, and notice that he’s not a neoliberal. He’s not a socialist. But no, he’s not a free marketer. Likewise, PiS in Poland has expanded family grants and downward some not substantial, but some measure of downward economic redistribution. The United States’ Republican Party more or less stands out for its commitment to feeding the rich and using culture to get voters to fall for it.

John Torpey 33:29

So what about Germany? I mean, obviously, a number of people have been concerned about the Alternative for Germany and its significance and winning have a significant number of votes in the German parliament seats in the German parliament. But they’ve become nastier than they were when they started out, which was a kind of anti Brussels party apropos your comments about power relying in Brussels. And then with the immigration or refugee crisis, so-called refugee crisis of 2015, they took on a different coloration, but they don’t seem to have a lot in the way of a kind of fascist kind of coloration. But I’d be curious, obviously, what you would say

John Torpey 34:14

So do I understand you correctly to be saying that contemporary Germany is sort of not the Weimar Republic, that is to say, its grounding in liberal, democratic civic nationalism, etc. The various kinds of ideas that you’ve talked about, in the course of this discussion, now rooted sufficiently strongly in, shall we say, democratic soil, that kind of collapse is not easily imaginable. I’m not saying it’s impossible.

David Abraham 34:14

Well, no one wants to see a party that describes Nazism as a mere bird poop drop in German history, and criticizes the Holocaust memorial in Berlin as a masochistic monument to undermine legitimate German national sentiment. No one wants to see a party like that hit double digits, even if it’s the low double digits, but their high tide was in the anti-immigrant reaction 2015-16 lasting into 2017-18, etc. They have twisted themselves into knots. They, for example, are the party most sympathetic to Russia in the rest of the Ukrainian war. It’s very hard for a party that denounces communism to suddenly become Russophile even if Putin distanced himself completely from the Soviet Union. I think they’ve seen their day. They will be around, but I think they have seen their day, I don’t think they’re a serious threat in Germany. Their strength, and we must also we have to remind ourselves, was overwhelmingly in the former East Germany where resentment that being treated as poor primitive cousins of the sophisticated folks in West Berlin and Dusseldorf in Frankfurt, [which] created a kind of “spitefulness,” which led folks in the East. And here we could talk about different forms of coming to terms with the past communism and East Germany in some ways, got rid of people who were actual Nazis, but never became kind of anti-nationalist in the way that West German culture became kind of anti-nationalist. So I think with the slow but steady economic revitalization of the East, the ground for the Alternative for Germany for the far-right, Neo Nazis, etc, probably stabilized and declined.

David Abraham 37:15

I agree, nothing is impossible. But I think the foundations of liberal democratic German state are very strong. And the opponents of that state are not many. There are other troublesome issues like whether a joint European defense system is possible, or if what happens as the United States turns its attention to China and NATO. It was Donald Trump, who said, “what do we need NATO for anymore if there’s no more Soviet Union?” That is a key issue. And what we’ve seen in recent months is that the rest of Ukraine war is in some way being used to bring our European NATO partners to heal and to get them to spend more on defense and become starcher allies. One point, many on the left, we’re seeing Europe as a kind of third way between communism and Anglo-American brutal capitalism, that hope or that possibility is probably gone. The Greens in Germany are not socialists. They’re much more like our progressives, and they are like their Social Democratic colleagues. But being a system of proportional representation, it’s possible for the two parties to run separately and then join a coalition together. In the United States, you could never do that, you could never have the Bernie Sanders party, and the Wall Street party reach some kind of coalition agreement after the election. It’s one or the other. The Greens in Germany represent non-social democratic enterprise that will change the character of Germany into a more post industrial postmodern party-like Piketty Brahmin liberals, and whether that will leave a shrinking Social Democratic Party in Germany remains to be seen, but I don’t see a fascist outcome to that evolution.

John Torpey 39:32

Right. Well, let’s thank God for small favors, as my mother used to say. So that’s it for today’s episode. I want to thank David Abraham for sharing his insights about social democracy and welfare states in 20th century Europe and beyond. Look for us on the New Books Network and remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance as well as to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.