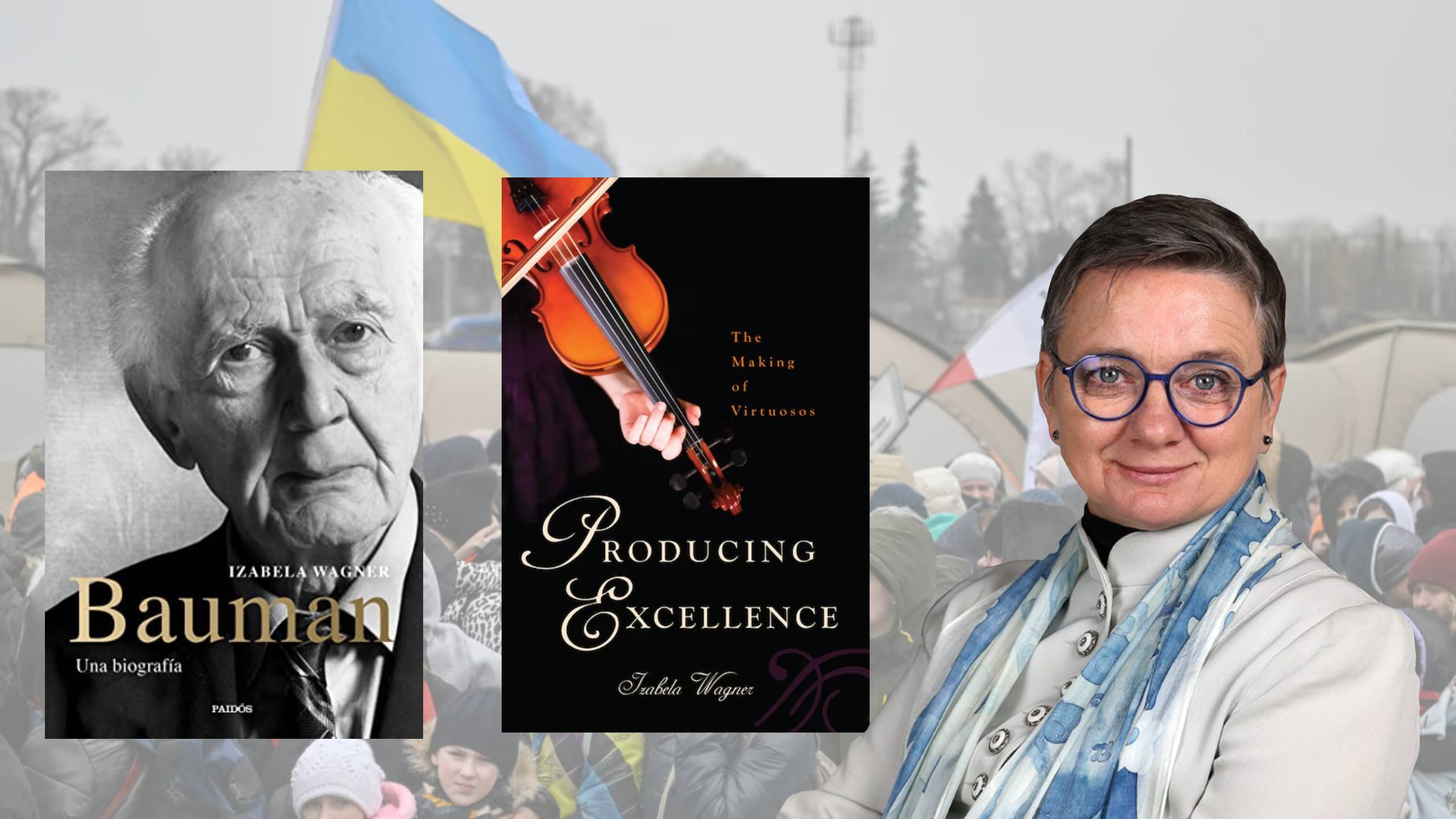

Bauman, Virtuosos, Liquid Love and the Refugee Crisis in Eastern Europe: The Eclectic Research Agenda of Izabela Wagner

In this episode of International Horizons, we are joined by Izabela Wagner of the Institute of Sociology at the Collegium Civitas in Warsaw and Fellow at The French Collaborative Institute on Migration in Paris. She discusses the sociological factors behind the success of virtuoso musicians and on the social pre-conditions of professional excellence. Wagner also delves into the life of Zygmunt Bauman, his works, and how to understand his innovative theories such as the notion of a newly “liquid” world that followed the solidity of twentieth-century society. Finally, Wagner discusses her reasons for using biographical approach to social life and the latest developments in the refugee crisis in Poland, in which the government has selectively supported Ukrainians while neglecting to help people from other nationalities now awaiting admission on the border with Belarus.

Transcript:

John Torpey 00:00

For the Polish-Jewish social theorist Zygmunt Bauman became a worldwide intellectual figure after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent opening up of Polish social sciences. He was especially well known for his study, Modernity and the Holocaust, which placed the Shoah in the frame of larger features of modernity, such as bureaucratization, and rationalization. And that made him a worldwide figure, after which he went on to make other important contributions to contemporary sociology.

John Torpey 00:49

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast and the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey 01:09

We’re fortunate to have with us today Izabela Wagner, who is Associate in the Institute of Sociology at the Collegium Civitas in Warsaw, and fellow at the French collaborative Institute on Migration in Paris. Much of her research has focused on the social conditions of work for artists and intellectuals. She has recently completed a biography of Zygmunt Bauman, which appeared in 2020 and is simply titled Bauman: A Biography. Thanks for being with us today, Izabela Wagner.

Izabela Wagner 01:42

Thank you very much for having me.

John Torpey 01:44

Great to have you. So before we start on Bauman, perhaps you could start by telling us a little bit about your earlier work or other work on violinists and other artists, which obviously, is an unusual kind of thing for sociologists to study. But what have you found in your studies of people who play the violin and social circumstances of artistic creativity?

Izabela Wagner 02:09

Yes, this is a book called Producing Excellence: The Making of Virtuosos. And this is a book about how someone became virtuous. So this is not about this classical typical upbringing. It’s about socialization being outstanding. And this is absolutely a sociological book about the process of becoming part of the elite (very narrow) and which takes place [within] 20 years in a very specific environment, surrounded with exceptional people. And what I found –and what I was looking for– it was all sociological processes behind, which are usually hidden, and also not always known to musicians themselves because they see their own case, and they’re within this very particular environment of parents and professors and competitions. It’s a very competitive media.

Izabela Wagner 03:15

And I have investigated over 100 people [that were] engaging in this process. So I deconstructed the idea of talent. So talent is only a departure; it’s only a potential, but after you have very different and sometimes contradictory actions that should be there and processes. So this is a very complex issue. And I was surprised because this book was chosen as one of the best books about the millennials by Malcolm Harris here in the United States. So even if my sample was not just focused on American musicians, he found that it was a very good study for understanding the competition world, investment of parents, and all this sociology behind the production of excellence.

John Torpey 04:12

Right? So was this Malcolm Gladwell.

Izabela Wagner 04:15

No, it was Harris. He was also a journalist and specialist. Gladwell didn’t read this book, but it was something which probably could have [attracted] his curiosity because it is also about those hours and hours. But I’m not focusing on that, I’m focusing on how those hours should be done in a sense of lost social interactions.

John Torpey 04:15

Well, it sounds like it confirms this axiom now that the way to get anywhere is you have to spend 10,000 hours or something doing whatever you’re trying to get good at.

Izabela Wagner 05:01

Yeah, but it depends with whom and how you’re spending it. So this is why sociology is very useful here to understand that this is a very important process of selection of your collaborators, because I’m working on careers. And for me, career is not only one person and his/her career. It’s all this environment that you don’t see: generations before — sometimes in intellectual careers and artistic careers, certainly almost — and a whole staff of people behind you who were working, even if they don’t think that they’re working like parents for example (who are very important figure in the production of a virtuoso).

John Torpey 05:48

I mean, did you look at the United States? Or was this all in France? Or were there various places around the world?

Izabela Wagner 05:55

Yes, that is an international milieu. But International in a sense of mouth; does not mean cosmopolitan, but international with different nations is important there. And previously, it was the Soviet School of Violin, which was the most important. And this story was also historically grounded. And after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the best professors went abroad and developed different schools, etc. American violin school has roots in this part of the world. And I did my study in Europe, today I would come here and extend my study to American settings, but it was done [mainly] in Europe, [and] it’s also a one way ticket to the United States. So there’s no specificity.

John Torpey 06:53

Right. I’m curious, totally unaware, really, of the research on this, but there’s this tendency that one now sees in young American settings. Were there lots of Asian kids learning, I think, primarily violin but I guess maybe secondarily piano, and particularly sort of training on the classics of classical music. And it’s always a little what attracts them to America and Western classical music.

Izabela Wagner 07:32

Well, music itself certainly too, but it is also – mostly for me as a sociologist — I see there the sociological phenomenon, and this is again, excellence, [a] production of excellence. Not in sports, but in music. But also it is well-known among parents. And those parents were so focused on their kids that we obtained with the violin and other musical practices — but with violin particularly — the speed up of the brain function. So it’s even this perspective [that] “I will push my kid also because this is good for his general education, etc.” My book was published in Chinese immediately, you can imagine. It was like on top of the shelf, and also in sociology also recognized as one of the best books in sociology for the year when it was published. But it is not a manual of how to become, it is very critical. So it is a critical approach. And I showed that a lot of people in this trajectory are broken, because the expectations are very high. But we taught that [for] these expectations, and their hopes and dreams, you cannot practice as a child several hours per day. Because this effort has to be justified, and the passion should be awakened on how you do this, only dreaming about being on the Carnegie Hall stage is not enough. And all is about that.

John Torpey 09:20

You know, the famous joke about how do you get to Carnegie Hall? “Practice, practice, practice”

Izabela Wagner 09:25

Oh that, yes! And actually on the web, you can find amazing [auditions]. During the pandemics, it was very hard for everyone, but for musicians in particular, and it was these two American students practicing violin that developed a very popular kind of audition, and it was called, “practice, practice, practice,” you’re right.

John Torpey 09:53

So I’m now very intrigued by this, I have to say, and so I guess the question I want to ask is this sociological question about who is more likely to achieve excellence? Are there, as I might say, non-meritocratic bases of meritocracy?

Izabela Wagner 10:13

Yes. But do you have to know that everyone who is on this trajectory at one moment is excellent, but how to achieve visibility? And here, we have not meritocratic — and sociological absolutely — features that they are coming in processes, because this is a little bit different [than] actors, for example. Because in violin, to perform “Capriccio” from Paganini you have to practice [for] years. So, you have to get into this level of technicity. So, this is why I’m saying they’re all excellent if they are able to perform well, or acceptably in this program. But after, everything is a matter of sociology.

John Torpey 11:09

Yeah one imagines that wealthier people are in a better position to get the lessons.

Izabela Wagner 11:16

Yes but you know? Wealthier people, they will perhaps not invest so much as parents of musicians. I met parents who sold their house to buy the violin, because a good violin is like a good car in a race. So if you invest, the prices are over several millions of dollars or Euro. So there’s a beautiful story in this book behind all this crazy passion.

John Torpey 11:46

I’m now feeling like a bad parent. But anyway.

Izabela Wagner 11:48

Um, I don’t know. Because you can think that bad parents are those who invest so much because it’s a huge pressure. And for the young kids [that] aren’t coping very well with this because they’re young, but after a very critical moment when they become adolescent and you realize what’s going on with “me” and with all this.

John Torpey 12:12

So in other words, if you’re not going to be the superstar, maybe it’s hard on your mental health.

Izabela Wagner 12:19

Exactly. On your wellbeing. I don’t know about mental health, but some cases, sure. But on your wellbeing, yes. But those people are excellent scholars. So if you think from the perspective of academia, hiring someone, or when you select people for Ph.D. programs, etc. Those who achieved a kind of level in music, you can select them, they know how to work.

Izabela Wagner 12:36

And they tend to be perfectionists. So for better or worse.

Izabela Wagner 12:55

Absolutely, they are already excellent. Yes.

John Torpey 13:00

Well, all right. This is fascinating. And I hadn’t expected to get into this quite so much, because we were sort of talking about your Bauman book. But as I said before we started recording, Bauman is a very significant figure, certainly in Europe, and in certain respects, is or was in the United States. But I think there’s a difference in the kinds of things that American sociologists tend to study and be concerned about and that sort of thing. So I think there’s a Zygmunt Bauman Institute, I guess it’s called, at the University of Leeds, but it’s harder to imagine such a thing here in the United States. So, anyway, maybe you could talk about how you understand his contribution. As I was saying in the introduction, Modernity and the Holocaust was a very important book to me, in part because there was so little sociological attention to the kinds of [bureaucracy] of the Holocaust, which is so pervasively important in history and to some extent, political science. So, anyway, tell us what you found out about Bauman by writing a biography.

Izabela Wagner 14:17

It was a long process, and I was not a “Baumanist”. I am saying I was not because I am educated in France, where Bauman is considered as a kind of an important public intellectual, but not apart from this book, Modernity and the Holocaust. France is a little bit exceptional, because Bauman is very popular and extensively practiced in all Latin America and Mediterranean countries and also in Scandinavia, etc. So he had this large repertoire. He’s so eclectic, that some environments and the places are focusing and taking from him what they want? Yes, because of globalization, consumption, etc.

Izabela Wagner 15:16

Now I’m saying that I’m Baumanian, because I’m working on refugees as a phenomenon, also, as a field. I’m ethnographer, actually. So this is why I see the huge potential in Bauman works for the 21st century, [where] our biggest problem, which is the refugee phenomenon. And Bauman Institute was not his creation, he was quite skeptical about this. It was his Ph.D. student, Mark Davis’ creation and it works very well. He was the first director. After there’s other directors and each director probably is giving more his — it was always a man, we will see later perhaps in a future — impact on what’s going on here, it will be critical theory and globalization focus. But one part of the activity of Bauman Institute is Bauman’s legacy and archives because the family gave everything [that was] in his office in his computer even, the documents, etc. to the University of Leeds archive.

Izabela Wagner 16:39

So the activity of Bauman Institute this really diverse, but I think that the liquid barrier –because you didn’t mention it– Bauman’s is most popular in academia probably for Modernity in the Holocaust, but for the whole world. It will be [his] “liquid perspective,” I will say because he has several books with the “liquid” term mentioned or put in front. He joked a lot about this, he was tired of this. And when you see after 85 books that he published, you’ll see huge development of his ideas and he was not jumping from one to another, it is a very clear development. But the last part of his activity — and this is why probably a lot of sociologists could have trouble — Bauman wrote for everyone, his ambition was to discuss with a large public after his retirement. He said: “Okay, now I’m free.” And it was 1990. So he finished his work with the social theory, etc. and the extended means the social theory is always there, but the language is completely different. And he’s speaking not specifically about this country or that country. He’s speaking about social processes in general.

John Torpey 18:15

Right. So maybe you could talk about the liquid idea. And for those who are less familiar with it, including me, what’s that about? I mean, this is again, I think, a difference in European sociology as compared to American sociologists that tend to be more about specific countries, more empirical and more general kind of claims about the nature of social reality and things are looked at somewhat skeptically, I think, but that’s the kind of thing that was contributing.

Izabela Wagner 18:48

I think that knowing his life is something that helps you to understand his books. Why? Because he’s so general. And speaking about just this, some people are saying philosopher or essayist, but knowing his experiences, you can put the link and in that way you have this safe background for you to imagine that when he’s speaking generally, etc. It’s not like intellectual writing in his office; it’s really grounded in a biographical experience. So liquid, the term “liquid” was not put in this first position by him. It was his editor, at Polity Press, that found that it’s very good and they developed it as his metaphor, obviously. But it was one of the terms that he described as the change in our social life and even our social relations and in everything: institutions from stable and strong became a liquid, or relationship to work became like this, to love became like this. All social processes became liquid. Well, what is liquid? it’s not solid. You will stop working inside of the same company during the same trajectory. I’m not saying the same type of job, but you know, as it was 100 years ago. So this stabilization is gone. And we have to invent ourselves and to adjust.

Izabela Wagner 18:54

He also criticized this dream in which you were in charge of yourself, and you can do what you want: it means that you would like to become this, you have to put 2000 or 20,000 hours or days in your work. And you will then say “no, this is not what I like.” The system would like to make you believe in that, but you will be a kind of Kleenex. We become the Kleenex, this idea of instant adaptation, but it will not last forever, nothing will last forever.

John Torpey 21:27

But this is a claim about historical social change, things are now liquid in a way that they weren’t before they were more solid.

Izabela Wagner 21:36

Yes. But also in a relationship between people. Also, he published this book, Liquid Love, where he is starting from the very classical hetero relationship, but he’s expanding into other types of relationship, also to the interactions with neighbors, and he has this amazing chapter on refugees. So it is going on and on with the same idea: how our life changes, how we have no permanent frame and our frame probably is fragile and flexible. And [hence] the word liquid.

John Torpey 22:19

Right. I’m, you know, deeply and profoundly aware that the kind of life I have, because I have tenure, is unlike almost anybody else’s life. And since I appreciate the freedom from fear about losing a job and that sort of thing. There’s a lot of concern with ideas, for example, like universal basic income, that is just going to lead people to be lazy. And my reaction to that is to say, I don’t know, I feel more secure. And I therefore feel less worried about doing experimental things and trying things that I might not have tried otherwise. And, advocates of universal basic income have made this sort of argument. But I think, I suppose to some degree, it’s an empirical question. But in other words, there are things that one could do to mitigate the liquidity of the social world that we live in. And, this way, in some ways, it goes back to the idea of the welfare state, in the [United] States the New Deal. There were these four freedoms, one of which was freedom from want. And, I’m inclined to think that from a certain degree of security, it’s probably true that if all people’s wants are taken care of, they may be less inclined to take risks and that sort of thing.

John Torpey 23:53

But nonetheless, with a certain kind of minimal foundation that you don’t have to worry about, [such as] starving to death. I would think that would give people lots of freedom to try different things and be more inventive and risk taking for society. I mean, for themselves, of course, but also for society.

Izabela Wagner 23:53

Yes, absolutely. And Bauman saw this reform and saw the change in this negative way. Yes, he was absolutely supportive of this idea that we should have a decent life. And he was an excellent observer, and he was very sensitive to poverty. Wasted Life is another book that he devoted to those who we don’t see even; you know, they’re there. And this is how he’s always said that this is at the cost of our development and progresses. The amount of people that are homeless and the amount of people that are jobless and the refugees and immigrants — illegal immigrants or illegal immigrants — etc. So he had this focus on that population.

Izabela Wagner 25:14

And about your question of this level of basic stability and safety: absolutely. We see several papers published in our academic work about what we are doing as a progress, and how we conserve the knowledge. And when you are precarious, what you’re doing, basically, it’s not thinking about your future discoveries, about getting the publication, getting the job for applying for the position, etc. So this competition, crazy competition, puts you in a situation of inefficiency. It’s crazy to think that we are more efficient. A little bit perhaps, but in this context that we have actually today, we have the empirical, very good promise that the scientific progress is now down because of this contest.

John Torpey 26:10

Right. Again, to go into this a bit further, most people seem to be near terrified, and the more terrified they are, the more you can get them to do what you want, as far as work is concerned. I mean, whether it really works out all that well, I suppose is a different question, certainly for the workers. But I think the more stability that I have, the more you’re inclined to try new things. And there is, this could be my own individual psychology rather than something generalizable, but it seems to me that if I had that kind of floor that protected me from destitution, and hunger, I would be not selfish and self seeking, but grateful to the society that does that for me. Now, again, maybe that’s my own individual psychology.

Izabela Wagner 27:06

It is very interesting that you’ve pointed out this. Bauman was a socialist, and he was convinced that this basic healthcare should be extended, and he paid for, etc. etc. In the UK, you have this process where they’re going in the inverse to Obamacare decisions, and he was sick, and he refused to be the patient of the private system. He waited for his turn, even if he had money for going to the private [practice], he refused it. He said, “why me, as a richer person or a different person, should I be different from other people who paid the taxes as I paid, etc. who worked here. It isn’t just.” And he protested against this injustice. And [he] himself and some of the members of his family said that perhaps he will, he could have lived longer.

John Torpey 27:43

They weren’t happy with that particular choice.

Izabela Wagner 28:20

Yes. But he said, “No. No specific treatment because I have money.” And he was only on the basis of numerical level. So it is really a conviction to the end and deep conviction because it is about the life in his case.

John Torpey 28:38

Right. So I want to kind of switch gears and ask you a question about writing a biography. I recently had the occasion to talk with somebody about his new biography of Ralph Bunche, the namesake of my Institute here, and obviously a very big significant figure in the mid 20th century, American politics, and world politics. But like him, this is your first biography. Think of yourself as a biographer per se, you said you were an ethnographer. So what was that like? Why did you decide to do that? You know, would you ever go back to doing something else? Or is it biography all the way down? As far as you can see now or?

Izabela Wagner 29:24

Yes, it started with the project to have a chapter about his career. I would like to [work on] the book, Looking in the Mirror, and about sociological careers of other famous people and extreme cases, as I am “Hughesian” after Everett Hughes. I like the extreme cases because it shows you the mechanism very well. And Bauman was the case of the career of the person who is in a situation of changing the language, which is important for us. And it is a huge challenge, but also this incredible development of career at the time of his retirement, but also of this very difficult tension that he experienced: that he was so loved, and admired in almost the whole world. And he was almost hated in Poland, and he was rejected in Poland, etc. So, it was an image, he had this very different image from one place to another. And I did the first interview thinking about this chapter. And after I asked him if I can go to the IPN Archives, which is the Institute of National Remembrance. And this is the Secret Service police [and] Secret Service archives, that are open to journalists and to researchers.

Izabela Wagner 31:08

So I could consult his fights, the fights about what he did, etc. And there I found that contrary to what is largely shared in Poland, this conviction that he collaborated with the system, he was a part of the system for a long time etc., he was very against or tried to do something in order to fix the authoritarian and bureaucracy, yes. Doesn’t mean not being any more a Marxist, this is not changing. Making Marxists more Russian, yet more human open, they use these terms. And I saw so much evidence and he had no biography actually, from the point of view of the writings about him by non-Polish people, it was a complete misunderstanding of the context. Because the Polish context is quite complex, and he was a Polish Jew, and [there is] this tension in identity: he always claimed that he’s both, he has this mixed identity, which was put under questioning in Poland. It’s a very complicated position.

Izabela Wagner 32:32

So I saw that it would not be enough [for] one chapter. And I started to write his biography, but this is not an intellectual biography per se. It is the biography life in the context. So this is why I probably have good feedback from historians also about the history of Poland and especially Polish-Jewish relationship in the 20th century. [Mainly] because he’s like an amazing case study for showing how it evolved or removed from interwar racist policy and social norms — and policy as well as social norms — really deeply grounded in society, and how despite the change of the system, the social norms are there. And how despite of these political changes of the 1989, Bauman after 1968 was claimed to be enemy of the state number one, and after 1989 he became also kind of enemy of the state of at least right wing and and all these people who believe in Judeo-Bolshevism concept. Yes, he’s like a Weberian ideal type of Judaism in Poland.

John Torpey 33:52

Interesting. Well, obviously people should read the biographies. Sounds fascinating.

Izabela Wagner 33:57

Just one word. I’m working on another biography. Yes, and it is a biography of a wonderful woman. Also a 20 century life. She was born in 1922. Her name is Alina Margolis-Edelman. She was pediatrician, and co-creator of Doctors of the World or “Médecins du Monde.” And you have here also in the United States a brand. And I think even in Europe. She was Holocaust survivor. And she has an amazing biography. And she was the wife of Mike Edelman, the hero of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. And his life is well known, and he was a public figure. She created several missions. For example, in El Salvador. She opened up hospitals in Africa. She was in Yugoslavia just after the war, etc. So she’s like the leader on humanitarian actions and humanitarian missions in the world. And she’s invisible. She’s also a woman, so that will be the story.

John Torpey 35:33

Interesting. So you are gonna do another biography. All right, we’re kind of running out of time. But since you’ve mentioned that your current work really focuses on refugees. I want to ask you about the refugee situation in Poland. So you don’t really live there these days. But sure, your sources of information are many and good. So maybe you could tell us about it; there was a huge influx of refugees from Ukraine a year ago. We are recording this on the first anniversary

Izabela Wagner 36:06

Yes, today is a very sad day. And yes, Poland. I just checked the statistics on the border. We saw ten millions of entrances from the Ukraine border, mainly, but also eight millions who go back. That is the males who will be engaged in the war but who were coming for their women because of the huge restriction for men to come, they are needed. Today we have in Poland about 1, 2, or 4 millions of refugees from Ukraine. And it was a huge effort, because we had those peaks and it was for millions in spring.

Izabela Wagner 37:03

And [there was] this huge effort, and I was amazed to see how the civil society actually acted, because from the point of view of the government it was a big story. They took for granted the achievements of civil society, but it was really an organization, an amazing organization [based] on volunteering. People who took in, at home, the families, entire families. However, I should say something, which has been very sad for over one and a half years: we have a very hard situation on the border with Belarus. And there we have refugees. They are coming from Asia, and they are coming from Africa. They’re coming from Afghanistan, and mainly from Syria. They’re refugees, yes, for several years. And unfortunately, our authoritarian government is acting against international law. And there’s a push back in those people, even pregnant women, even children. There are people that are missing, people that are dying. Because yes, there are some researchers, sociologists, anthropologists, historians, etc. They are in the forest (virgin forests), and with the climate there, and also hostility, those people are dying. And this is incredible how human rights are violated and how we have the same society that can help one population and [not] other populations, which is in exactly the same case even not worse.

Izabela Wagner 38:48

So here, it is very difficult because human rights depend on your skin color. And that is something which probably we should work a lot on in Poland. And we have many activists, doctors, researchers who are there, but not enough. And they are also in a situation of acting illegally because some laws were created. Specialists of international and Polish law are claiming that this is completely illegal. And as soon as this government is changed, a lot of people will be charged for this. For instance, the situation is horrible with those refugees.

John Torpey 39:37

Right. Well, yes. I’m afraid that we’ve sort of forgotten about this whole other refugee crisis, so to speak in Poland with the massive influx.

Izabela Wagner 39:48

One thing which is very interesting and horrible, is that there was a law created to prevent the presence of the humanitarian organization in that part of the country on the border, which is horrible. And the second thing is that the local population is making an immediate connection with the Holocaust, meaning that they’re speaking about hiding people again as they did previously for those who did it. Yes, because we know that it was not so obvious. But this connection, in reality, the people are hidden again. Yes, because they’re in the situation of being pushed back, which is today, equal to the combination to that.

John Torpey 40:42

Well, on that sad note, we’re gonna have to wind up for today but I want to thank Izabela Wagner for sharing her insights about Zygmunt Bauman and about contemporary Poland, and his, Zygmunt Bauman’s, contribution to sociology. Look for us on the New Books Network. And remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance as well as to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons”. That is the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us. I look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.