China Goes to Hollywood: China-US competition for soft power with Erich Schwartzel

What do the patches in Tom Cruise’s jacket tell us about China? How is China shaping the entertainment? What do the preferences of Chinese moviegoers tell us about the role of the US in the world? Is China learning from Hollywood in its efforts to woo people around the globe?

This week, RBI director John Torpey talks with Wall Street Journal Hollywood reporter Eric Schwartzel about the past, present, and future of the Chinese film industry and how it is all related to soft power. You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud below. You will find a transcript of the episode below.

John Torpey 00:15

China has been on the rise for some time as an economic and technological competitor of the United States. But many observers would say it lacks one crucial thing that the US has in spades, namely, what’s known as soft power. American music and films have seduced the rest of the world and endeared the United States to people around the globe for decades. Can China develop its own soft power?

John Torpey 00:41

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey 01:01

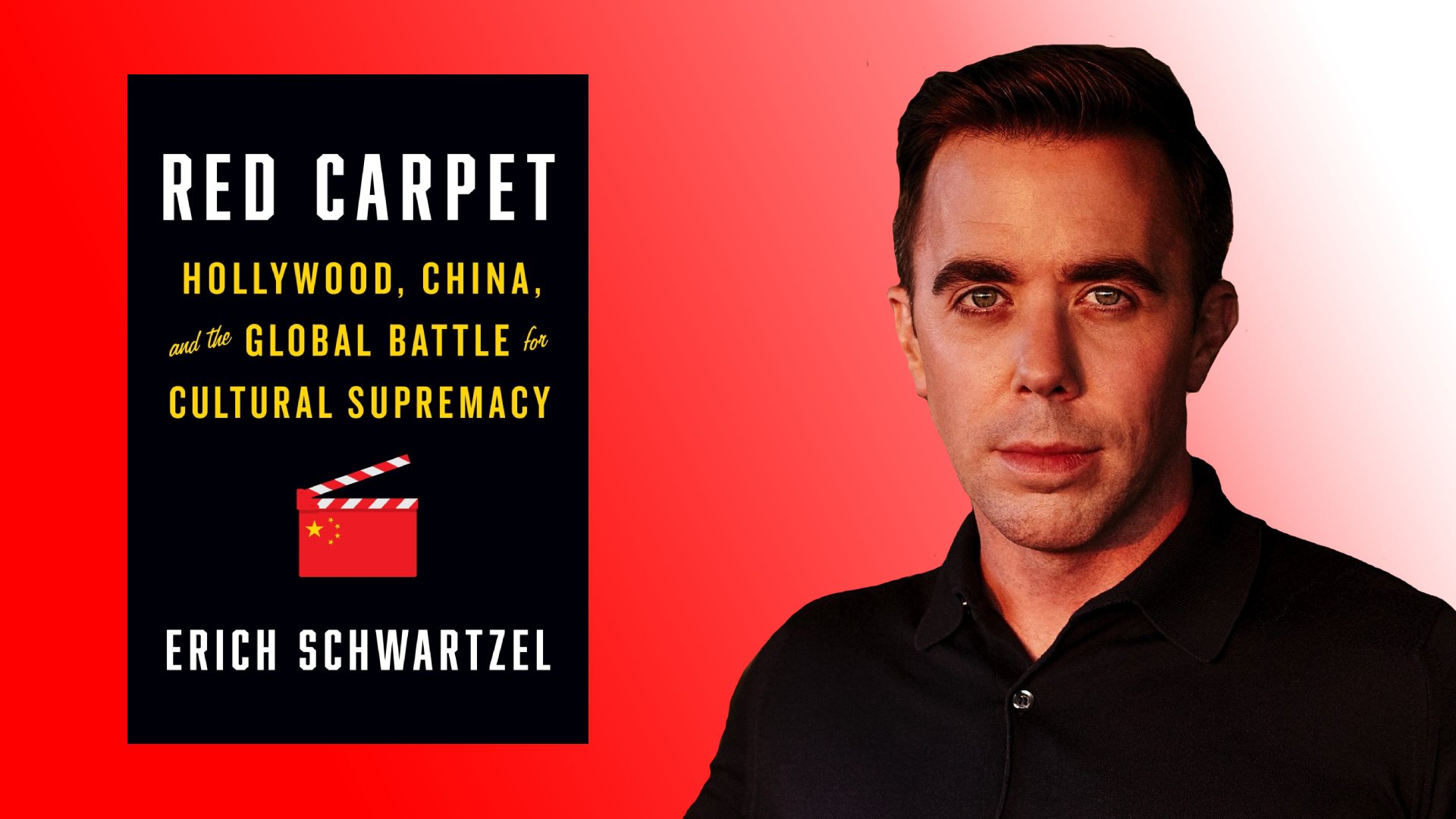

We’re fortunate to have with us today Eric Schwartzel, author of Red Carpet, Hollywood, China and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy, which addresses these issues from the perspective of film and the movies. Eric Schwartzel has reported on the film industry for The Wall Street Journal since 2013. He previously covered energy in the environment for the Pittsburgh Post Gazette.

John Torpey 01:27

Thanks so much for joining us today. Eric Schwartzel.

Erich Schwartzel 01:30

Hi, thank you for having me.

John Torpey 01:32

Great to have you. Thanks so much. So you say in the book that it’s essentially the story of what has happened in the relationship between Hollywood in China during the interval between the original “Top Gun” movie with Tom Cruise, and Sam Shepard, and all these people in 1986, and the remake or the sequel, sorry, “Top Gun Maverick” in 2017. Can you sort of tell us about what happens in that interval?

Erich Schwartzel 02:00

Sure. I mean, the two Top Guns are these perfect bookends, because the original when it comes out in the mid 80s, is the ultimate example of I think American soft power on screen, right? It’s about these amazing naval fighter pilots. Tom Cruise is the best looking fighter pilot in the world. You’ve got the sweep of cinema. And really, I think an example of a moment when Hollywood was really seen as doing America’s bidding, not just in its portrayal of military might, but also just in its cool quotient. After the original Top Gun came out, not only did enlistments in the military increase, but so did Ray Ban’s sales.

Erich Schwartzel 02:52

So you really had this incredibly effective marketing tool for the country in a movie like “Top Gun,” and that’s not just the only movie around that time. I think you could also put “Dirty Dancing” and “Back to the Future” and a bunch of hits like that in the same bucket.

Erich Schwartzel 04:03

Starting in the mid 90s, Hollywood movies started flowing into Chinese theaters. And then about 15 years later, around 2010, its box office started growing at a clip. Not only growing at a clip, but also growing as American ticket sales were flatlining. So a lot of studios, which were already becoming increasingly global in their consumer base, started looking toward China has this economic salvation. But doing work in China is not like doing work in Thailand or India or even Russia. To maintain access to those theaters and that revenue, every movie that gets released there has to be approved by Chinese censors, which means it cannot have anything in it that that censors deem politically, morally, culturally problematic.

Erich Schwartzel 04:57

And that explains why the patches on Tom Cruise’s jacket had to go. Because the Taiwanese flag implies a Taiwanese sovereignty that contradicts the One China Policy. And relations between the Chinese and the Japanese have always been somewhat charged, especially in more recent years. And so the Chinese financiers, who were on the “Top Gun” movie said to the producers, “it might not be the worst idea in the world to put some new patches on Tom Cruise’s jacket.” And so suddenly, you have an instance here where this movie that originally started as the ultimate commercial for America is instead now the ultimate example of how the American movie is going to be expected to placate Chinese officials.

Erich Schwartzel 05:49

And I think the important thing to note here is that when all of this was happening a couple of years ago, when the new Top Gun was being marketed, Chinese officials weren’t weighing in at all. No one from Beijing said a word. This was all done because studio executives in Los Angeles had ingested what was allowed and what was not allowed. And they knew what to self-censor, before the censors could even get involved.

John Torpey 06:19

Well, you used it, of course, I was precisely going to ask this question about censorship and self-censorship. But I mean, in a certain sense, we could put this in a broader frame, right? This is really a sort of an aspect of a larger sort of mutual dependency and sort of as I read this part of the book, I remember thinking about Neil Ferguson’s notion of “Chinamerica”: the idea that we can sort of somehow separate ourselves from them. And it’s become obviously very clear, once again, in the course of the pandemic, because they make all these protective devices and equipment that we needed, and we didn’t have them. And, Trump was going to bring back a lot of that manufacturing, I don’t think that happened very much.

John Torpey 07:06

But I guess the question is, you know, how does the lever, the sort of element factor of entertainment and film help us kind of understand the larger relationship between these two countries? I mean, obviously, there’s a competitive relationship, there may be a military antagonism (not so clear). I mean, we still have a hell of a lot more military equipment than they do. But it’s not so simple. It’s not like they’re these two separate entities. What you’ve described as a relationship of codependency or something like that. So maybe you could talk a little bit more about that.

Erich Schwartzel 07:44

I think I think the concept of “Chinamerica” is helping me make a realization here, which is that the relationship between China and Hollywood started with China being dependent on Hollywood. It evolved into a codependency and I think we are now in a world where Hollywood is dependent on China. And I’ll break that down. So in the mid-nineties, the reason why Hollywood movies started being exported to China to begin with, was because Chinese movie theaters were struggling. After the Cultural Revolution, movie theaters reopened, and primarily were showing Chinese propaganda films and very dry medicinal documentaries.

Erich Schwartzel 08:29

As China’s economy modernized, and in the years ahead of its acceptance in the WTO, the Chinese movie theaters were struggling so much because, despite the Chinese propaganda being the only show in town, it was soon starting to see come competition from pirated movies -that were frankly more entertaining to watch- karaoke salons and television were starting to really eat away. And the Chinese theatrical market, small though it was, really needed an economic boost.

Erich Schwartzel 09:03

And so movies started coming into China like “The Fugitive”, “True Lies”. These big Hollywood spectacles that Chinese audiences had largely been shut off to for the past 30 or 40 years since Mao took power. And that really did provide this excellent economic boost to the to the theaters. By 1998, I don’t have the numbers right in front of me, but a handful of movies cause something like a 45% jump in the Chinese box office. Still we’re talking like really pocket change to the studios, but for Chinese theater owners, a massive stimulus program here. Then as China’s box office grows, there is a codependency because Chinese theaters still need the economic movies to goose their overall revenue. Hollywood starts to need the Chinese grosses to plug holes like the collapse of the DVD market that leaves a lot of studios struggling. And other aspects like I’d mentioned, like the like the stagnant ticket sales here in the US.

Erich Schwartzel 10:16

So there’s kind of a codependency there. And now we’re in a world where China has really learned and studied how America built its entertainment industry, to the point that China’s film industry is much more commercial. Its audiences are more and more preferring Chinese movies to American movies. And this Hollywood system that, over the past decade, has built up a real dependence on those grosses is seeing less and less certainty there in the form of Chinese tastes evolving away from American films, and also Chinese authorities letting fewer and fewer American movies in.

Erich Schwartzel 11:03

So the “Chimerica” model was definitely the case for much of this relationship. I think it’s looking less and less so now. And it’s really putting the Hollywood studios in something of a bind, because they have threaded themselves so deeply into into China. And every time, still today, I think, when a massive Marvel movie or a massive, “Fast and Furious” movie is put into production at something like $250 million, that studio is counting on a Chinese release. And and that Chinese release is less than less certain.

John Torpey 11:46

I see. So one question I had is precisely: has China begun to develop its own soft power, at least in this area? And I mean, it sounds like you’re saying they have and increasingly they’re amusing their own people. They’re not relying on outsourcing it to Hollywood, which I assume if you ever said that to a Hollywood studio executive, they would sort of recoil. I mean, they might sort of admit that it’s the case. But I would imagine they would not be happy about the idea that you’re saying that Hollywood studios are dependent on the preferences of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. I mean, that would not be good for business, I would think, in the United States. And yet, it’s something there, at least were, sort of dependent on sounds like.

Erich Schwartzel 12:40

Very much dependent on it. And, but I don’t necessarily know if the the success of China’s film industry and the commercialization of it has led to soft power. That is the that is the final leg of the race that is still being run. And so I think, certainly, internally, China’s film industry has been an incredible boon for Xi Jinping. Because Chinese filmmakers have learned often from Hollywood, how to make let’s call it good propaganda. I think Chinese propaganda films before let’s say 2000 or so were often incredibly dry, boring educational films and Chinese officials literally studied American movies like “The Patriot”, the Mel Gibson movie about the Revolutionary War, to see how to make a propaganda movie that doesn’t feel like propaganda.

Erich Schwartzel 13:49

I think there’s a real distinction to be made here. I mean, I think often times critics will call American movies propaganda. I see their point and I see the the propagandistic element of certain American movies. I do think we’re talking about a different level whenever authorities in China are putting movies into production, approving scripts, casting actors. I mean, that is more of a state effort than something like a movie like “The Patriot” is where it’s like a pro-U.S narrative. Or like, let’s say like a historically revisionist take on American history.

Erich Schwartzel 14:28

So but but anyway, so all of which is to say there have been examples now of Chinese movies like the the one that is best known in diplomatic circles is this film “Wolf Warrior Two”, which was this massive Chinese blockbuster that was essentially a version of China’s “Rambo”. It was about a Chinese soldier who has to go to Africa and save the villagers, win the girl. It’s like a classic. It’s like watching Rambo, but with a Chinese guy instead of an American guy. And the Americans look like the buffoons rather than the heroes. This movie was a massive success. And it really showed how effective popcorn entertainment, or propaganda disguised as popcorn entertainment, can be. Now but the big issue, the big problem is that, “Wolf Warrior Two” made something like $850 million, a massive amount of money. But 99% of that gross was in China alone, it was not as popular overseas.

Erich Schwartzel 15:37

And so I think soft power, as we’ve traditionally defined it, is an export. There might be some internal benefits to it, but it’s primarily been seen as this kind of colonizing or outside force. And China is still struggling there. I think there are places where, if you look, there’s significant inroads being made. Primarily in places like Africa and through things like the Belt and Road initiative, the massive collection of trade deals -what else is there- infrastructure loans, everything that has given China this foothold in major parts of the world, largely out of sight to most Americans, I think.

Erich Schwartzel 16:29

You know, that is functioning as something of a soft power distribution network. And, and I learned that whenever I went to Africa, and did some reporting on an initiative called the “10,000 Villages Project”, which is this pretty remarkable initiative to hand out low cost Chinese satellite dishes to African villages, that carry Chinese movies and TV shows on them. And so I was in Kenya talking to Kenyans, who love Chinese movies, and meeting young children who idealize “the Monkey King”. And so, there it’s working, it’s working in some parts of the world, but I don’t necessarily know how effective it would be in in the West. I think there’s probably still a steeper hill there to climb.

John Torpey 17:27

Yeah. So this is interesting, though, that we have this image or one reads things to the effect that what China’s really doing is kind of imposing a sort of debt servitude on African countries by loaning them all this money that they can ever, ever actually pay back, or building roads and bridges and things that the Africans can’t afford, and then they’re in the debt of the Chinese. But it does sound like, in a certain sense, may literally be softened by culture, by entertainment. And, I mean, I get that, you know, this may not do it for different populations in Europe, Western Europe, and the United States, or Canada, or whatever. But it does sound like it may be, as you say, may well be working, at least in those places where China has a presence, which itself is, let’s remember, historically unprecedented. They’ve ever really sought to kind of – it may or may not be settler colonialism -but they’ve never really reached outside of the Middle Kingdom in the way that they’re doing today.

Erich Schwartzel 18:36

Right, there’s quite a debate in places like Kenya, which is rather recently coming out of settler colonialism about whether or not this is a form of some kind of neo-colonialism. And so there are real concerns there. I think there are also a lot of political leaders and civilians who think that China’s pragmatic form of aid is what they need more than -in the sort of the American School- like, we’re literally building roads, literally building train stations and so on. And also, I think, from a political standpoint, staying out of Internal Affairs and staying out of or not raising issues about religious, corruption and things like that. So, that is that is certainly true.

Erich Schwartzel 19:30

And what you said about the culture needing to soften their arrival is a smart one, because I was in some villages, far outside Nairobi, where I was the only light skinned person outside of a Chinese person who these people had ever seen visit. I mean, imagine that. Think about how weird that must have been to have dozens of Chinese people show up seemingly out of nowhere. There had to be some kind of cultural introduction to the country, which I think these satellite dishes allowed. And then the other thing that you hit on was that there did need to be some winning over. I mean, in this this village [where] I spent most of my time in, Suswa, the Chinese had built a train station that is going to connect inner Kenya to Mombasa on the coast. And the construction was wildly disruptive. Like couple elephants died during it; some lions escaped their constrained area, because the construction. Dust that was generated from it had dried out crops. Like there were some real resentment over this construction that, you’re right; they needed to win the people back over. And, you know, I think a lot of the folks I talked to, they allow a kind of coexistence between Chinese, Kenyan and American entertainment. But there’s no real bias against Chinese entertainment that I think you would see in Western Europe or the US.

John Torpey 21:31

Interesting. So, in anticipation of this conversation, I sort of tried to think about why is it that some countries are seem to be better at, if you like it, soft power than others. I mean, China has, I think any unbiased observer would agree, and enormously rich historical culture, and music, and literature, and all these things. It’s not like they don’t have these things, but they don’t necessarily carry outside of their own sort of cultural sphere. And the United States, I suppose, in particular -I was watching this Beatles movie the other day, and thinking about these issues- that kind of stuff has been very popular around the world. People learned English that way during the Cold War. And, you know, I think it’s generally thought to have had these kind of implications of freedom and self expression and things that weren’t necessarily all that congenial to authoritarian rulers. But that doesn’t necessarily indicate or explain why there’s this uptake. So I wonder if you’ve thought at all about what sorts of limitations kind of there may be on certain cultures in the way that they are or not absorbed in other places? And what explains that?

Erich Schwartzel 23:04

Well, I think, it’s a fascinating question. And I think that one thing I learned when I was researching the history of Hollywood for this book, was just how much luck played into Hollywood becoming this global medium. When the movie was invented in the early, or I would say, would be late 19th century, early 20th century, Europe was really where the better movies were being made in the more sophisticated filmmaking cultures were, in places like Italy and France. And then when World War One broke out and production stopped on the European continent, because fighting with had broken out on the continent, it gave America this chance to catch up. I mean, no one could have anticipated, so they caught up in sophistication. And then the other point is that the French and the Italians largely saw the cinema as another place to reflect their culture. Whereas America, probably because it was a younger country, and maybe more of a maybe less of a homogenous country, saw it as a place to forge a culture. And so there’s a theory that it was sort of more of a unique fingerprint that made it more exportable around the world.

John Torpey 24:35

If I can interject just for a second, though, I mean, one of the things you said about what made Italian or European, French film the leading edge originally was its sophistication. And I would say it’s perhaps precisely the idea that you might say, in Tocquevillean terms, non-aristocratic cultures are not concerned so much about sophistication. They’re concerned about selling stuff. And Tom Cruise is a good looking guy. (And I mean, he’s only 5’6″ or whatever it is, but you never know that.) And, you know, because they figured out how to mask that fact, because he’s this good looking guy and people go to see good looking people. It’s not about the sophistication, you know?

Erich Schwartzel 25:19

Yeah, you’re right. I like that. I like that because when, when the American film gained an edge over the French or the Italian film, there were all these stories in the European press about how the American film was so déclassé and you’re exactly right. And it was so déclassé compared to their traditions of opera and theater. And it’s interesting, too, because it was another example of America occupying a role that China would 100 years later, where down to the point that America was seen as a place for kind of black market goods and knockoffs. It was just, it felt like it seemed like it was a real knockoff culture in much the same way that like, I mean, what do a lot of people think about China, they think it’s a place where you can go get fake purses and things like that.

Erich Schwartzel 26:17

So you’re right. I think that’s a great point. And there was absolutely from its earliest days, a sense of salesmanship. And actually, that was, it’s funny, I got a little obsessed with that whole idea whenever I was working on this book, because I think when you move to Los Angeles, you quickly see just that this is a real workday business. And you’re right, everyone is 5’6″. And, there’s a point in the book where I was interviewing some some folks who worked in what they called “hidden effects,” which are the special effects that aren’t the car explosions, or the big mutants or whatever. They are the people who go in and smooth out splotchy makeup. Or edit out an underwear line so that a woman appears fully nude. And I thought, “wow, these are actually the people who make the movies; this is what the movies actually need to work as entertainment, are those little touches.”

Erich Schwartzel 27:23

But anyway, back to your question about what makes a country better at soft power. I think you’re right about sort of the American approach being just more inherently appealing and more just kind of egalitarian or democratic and big tent. It was more of a big tent approach, right, than the Europeans might have taken. The other the other case study that’s bearing out right now, that’s been interesting to watch is Korea, which has had success with things like “Squid Game” and “Parasite” and K-Pop. Korea really is functioning on a level that I think the Chinese leadership would really love to see their own country do. A big distinction would be the fact that Chinese authorities would never allow the production of a “Squid Game” or a “Parasite”. And one of the things, one of the reasons both of those programs have appealed so widely and cut through is just how provocative they are. And there’s a level of not just violence, but there’s just a there’s a class commentary in both of those, in that movie and in that TV show, that would never fly in China. So I think if we’re going to look for something like what would China’s version of “Squid Game” be? What would China’s global TV phenomenon look like? It would be something much more family friendly, let’s say.

John Torpey 28:48

Right. So I mean, I don’t want the United States to take credit for it, exactly. But I wonder whether the American footprint or influence in Korea, would you say it has anything to do with the success of K-Pop and “Parasite”, I haven’t seen it, but you know, gatherers have sort of sharply anti-capitalist sort of movie but whatever. I mean, that’s it’s not so much about the message. It’s the question of how appealing this is. And of course, it won an Academy Award, I believe, right.

Erich Schwartzel 29:21

It did, it won best picture. I mean, what a fascinating question! I don’t know enough about how the Korean cinema evolved. I can remember, in the in the early 2000s, there were Korean exports that were very popular. And then there was a moment when Hollywood started looking toward Korean horror films to adapt into America. I mean, I remember “The Ring” was a Korean story that was adapted for American audiences. So there started to be this kind of exchange even back then.

Erich Schwartzel 29:58

What a great point, though, about America’s presence there. I mean, certainly, you know, it’s interesting. I think, I agree, yeah, we don’t want to say “well, yeah, they’re only good because they because of America,” but there is certainly something to be said for exposure like that. Like I interviewed for the book Ang Lee, who I think is now in his 60s, but so was growing up at a time when a lot of his contemporaries in mainland China were growing up in a Cultural Revolution that didn’t allow for much art of any kind that wasn’t strictly Maoist and filled with visions [that were] propagandistic. He, however, grew up in Taiwan, where he would go to the cinema with his mom and see Billy Wilder films and see all sorts of all sorts of movies like that.

Erich Schwartzel 30:53

They all share something in common, which is that they all started attending the Beijing Film Academy in the year or two after the Cultural Revolution. And when they started going to the Beijing Film Academy, there was a literal break. And while they were there, they started to be allowed to watch American movies like “The Deer Hunter” and “Casablanca”; movies that had traditionally been shut off. And so I don’t think it’s a coincidence there either that they became these arthouse phenoms. They made movies that got them banned in China, but around the world their movies were, you know, absolutely. rapturously received.

Erich Schwartzel 30:53

So I think that, yeah, there’s something to be said for exposure and exchange that can that can do quite a bit like that. I mean, similarly, in mainland China, after the Cultural Revolution, there was this group of Chinese filmmakers that came to be known as the fifth generation. And these are people like Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige, who, in the 90s, were these arthouse sensations making movies like “Farewell My Concubine”, “Raise the Red Lantern”; these movies that were just absolutely adored by arthouse audiences around the world.

John Torpey 32:19

Right, fascinating. So I guess just one last question: what do you think are the chances of China developing a sophistication in soft power that will give it traction outside of the places that you’ve discussed already, places that where they are providing infrastructure and loans and that kind of thing. Should we be worried? I mean, not that I’m exactly worried, but, you know, what are the chances of that happening? And I do sort of think that there is, as I say, a kind of intrinsic difficulties, that, what I would call following Tocqueville, that aristocratic societies have with sort of the idea of reaching a broad audience and sort of letting go of certain kinds of sophistication.

Erich Schwartzel 33:14

Yeah, I mean, because in China, there’s just an incredible concern with aesthetic and image, and sort of always putting a best face forward. I spoke to a young woman; she was a young woman when she moved to China in the in the 70s, who would tell me these stories about how she was in Beijing and it was just a it was a pretty gray and dismal place but anytime there was a military parade all of the trash would disappear off the street. And that is it is kind of a philosophy that extends to their cinema; every every movie is going to portray a developed, lawful, clean China which can have a kind of flattening effect. It can be hard to hook you in if everything looks so varnished and perfect.

Erich Schwartzel 34:15

And so it’s interesting like, I would say, if I had to predict, what could be like a “Squid Game”, what could take off like that? it would probably be something like a Chinese soap opera, which just because the soap opera as a genre has fewer the problems that Tocquevillean problems that you’re describing, right? It’s like it’s meant to be pulpy. It’s meant to be a little campy. And I know that Chinese soap operas are massively popular in China. I mean like, you can’t imagine how many soap operas are made and how many people watch these shows, and I know that they were popular among a lot of people I talked to in Kenya. That is a possibility.

Erich Schwartzel 35:08

But the bigger question would be like, does that do anything to change shifting American opinions on the country itself? And I think it could have some effect there. But it feels like we are, I’ve just even noticed in the two weeks I’ve been promoting this book, I’ve noticed a shift in the conversation, a conversation that used to be primarily the domain of people on the right is now becoming more of a bipartisan issue. And I think a lot of Americans feel very queasy when they hear about Western companies placating Chinese officials. And it feels like we’re reaching a moment where if pre-existing attitudes toward China would cut off any possibility of Chinese entertainment catching on.

Erich Schwartzel 36:12

And you’re seeing this in certain diplomatic circles, too. There this moment, especially during the Trump Administration, where Chinese officials met aggression with aggression. And they practice what they called “wolf warrior diplomacy”, which is like never, never bowing, never apologizing for China just going aggressively after any critic large or small. And there’s a sense in some parts of the CCP, I’m told, that has lost more friends than it has gained, and that they need to take a softer approach. And I think that would be required, I think, before any kind of Chinese entertainment might break through in the West, but I guess if you’re in Beijing, they might say, “Well, yeah, but who cares about the West?”

John Torpey 36:55

Right. We’ve got other fish to fry. Well, thank you so much. I mean, this has been a great conversation. You heard it here first, keep your eye out for Chinese soap operas on a cable TV channel. I want to thank Eric Schwartzel for discussing his fascinating new book Red Carpet and for sharing his insights about China’s use of the movies to expand its soft power.

John Torpey 37:20

Remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Oswaldo Mena Aguilar for his technical assistance as well as to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.