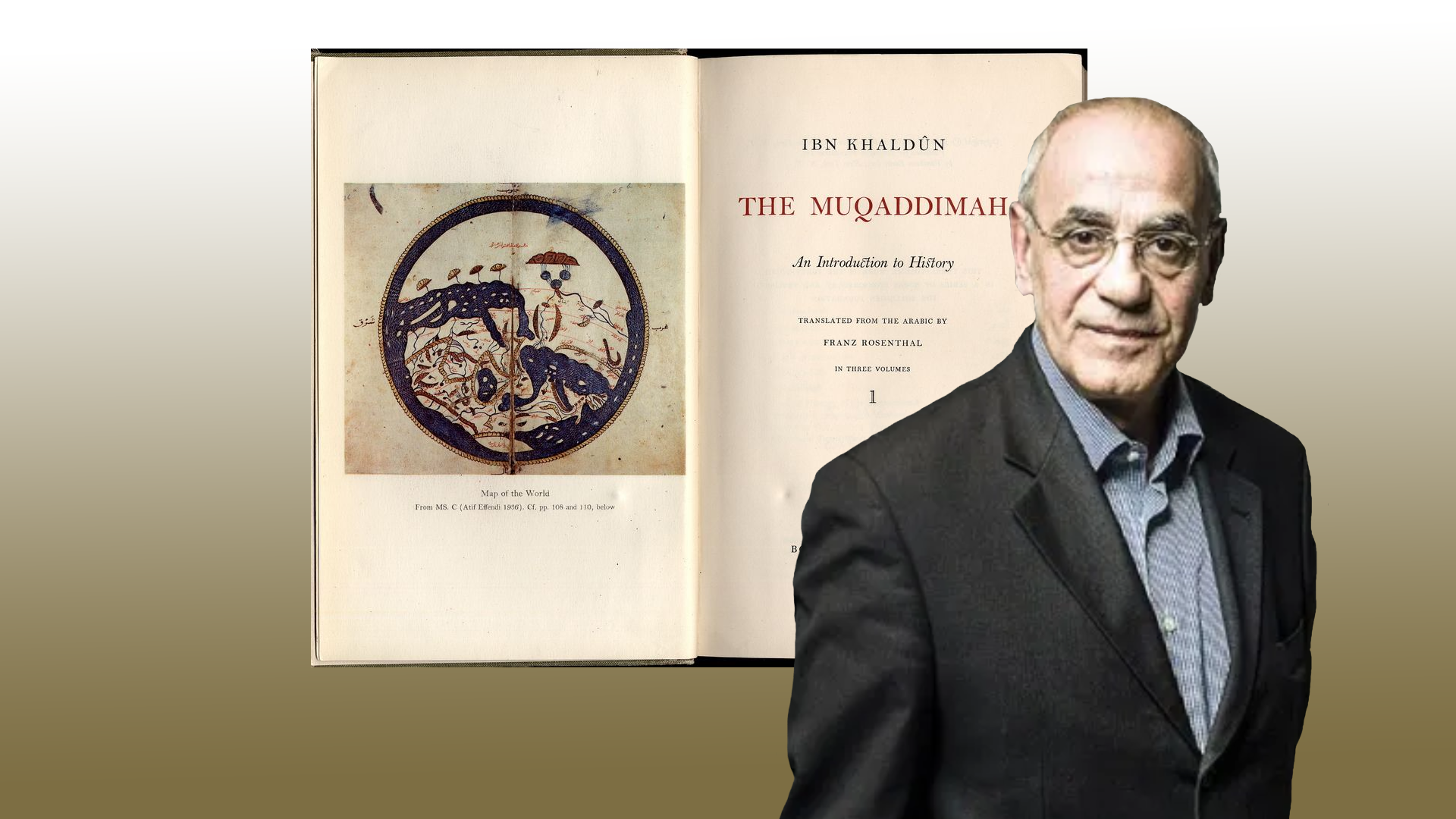

Ibn Khaldun’s the Muqadimah: The Best Book You’ve Never Read

Ibn Khaldun, the late 14th century statesman and historian, is regarded as one of the earliest social scientists on the strength of his classic, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. The book catalogues the political, social, and historical trends in Arab, Berber, Persian, and European civilizations in the Middle Ages and recalls Aristotle’s Politics in its encyclopedic treatment of social and political life. Yet regardless of its contributions to the humanities, it has been largely forgotten in modern times.

Aziz Al-Azmeh, University Professor Emeritus at the Central European University, talks to RBI Director John Torpey about the life, ideas, and significance of Ibn Khaldun and the Muqaddimah.

You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud below. You will find a transcript of the episode here or below.

John Torpey 00:06

The Arab philosopher and statesman Ibn Khaldun wrote a book several centuries ago known in English as The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to World History. It has long been celebrated as an approach to understanding the rise and fall of societies across time. What is The Muqaddimah, and how useful is it in understanding the course of human history? And what does it tell us about life and politics in the Middle East and in the larger world in the past and today?

John Torpey 00:36

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that bring scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m Director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey 00:56

To discuss the work of Ibn Khaldun we are fortunate to have with us today Aziz Al-Azmeh, who is University Professor Emeritus and distinguished visiting professor at the Central European University now in Vienna. He taught previously at the University of Exeter in the UK, and at the American University of Beirut, and has held visiting professorships at Georgetown, Columbia, Yale, and the University of California-Berkeley, the Aga Khan University, and the Institut d’Etudes Politiques that is Sciences Po in Paris. Among his books to appear in English are Ibn Khaldun: An Essay in Reinterpretation, Muslim Kingship: Power and the Sacred in Muslim, Christian, and Pagan Polities, and The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity. And he’s simply one of the few people I know who really know this work. And I want to thank Aziz Al-Azmeh for joining us today.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 01:55

Thank you. Thank you for having me. Thank you for the invitation.

John Torpey 01:57

Great to have you. So since this is a relatively unfamiliar name, I think we should probably start at the beginning and talk a little bit about you know who exactly he was. He was born basically into the world of the Black Death, at least in Europe, not where he was from, he was from Tunis, but maybe you could begin by telling us a little bit about who he was. And you know, what he did in his life aside from this book.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 02:23

Yes, while by all means, by all means. You know, apropos of being an unfamiliar name, in my personal experience, most people with a reasonable degree of literacy, have generally heard of him or were surprised that they hadn’t, when told about him. This particular book, or certainly, it’s a large book, but certain sections from it have generally been taught in civilization sequence courses, Columbia style, be it at Columbia or at many other universities worldwide. Ibn Khaldun himself was a statesman, but really an itinerant statesman. He’d had a life which spanned many countries, the whole of North Africa, Spain, Egypt and Syria in the 14th century, in the course of the 14th century, with a life that was marked in his early youth by, marked with the death of his parents due to the to the plague, that of the 1330s. He spent his life moving from court to court, playing courtier he was highly capable. He seems to have had a difficult personality and to have been given to intrigues. As a result of which he did not really last long in any of the, of the courts that he served.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 03:48

He spent the second half of his life in Cairo as a judge and a scholar. And towards the end of his life, he had a very interesting encounter with Tamerlane, at the gates of Damascus when Tamerlane was besieging the city. And he has left us in his autobiography a very interesting account of that particular encounter of the meeting, of the kinds of topics that they had discussed, of the idea that Tamerlane may have been predicted by the by the movements of the stars, and that is, his coming had been expected by quite a number of others, a kind of political eschatology, which was quite current that is, at that particular time. So much for his so much for his life.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 04:33

So a life which was very busy, highly charged, very interesting, with tremendous experience, hands down experience in politics as an advisor to kings, and particularly North Africa, as a person charged with raising armies. And as you may well know, those who are charged with raising armies usually obtain a degree of insight into the into the sinews of any political moments, which others do not necessarily have.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 05:02

At one point in his life, when he was in his 30s, as a matter of fact, when he had need to disappear for a little while, put his head down, he went and sat in an oasis in what is today Algeria, and composed the first draft of The Muqaddimah virtually out of his head, without access to libraries. He was a man of enormous erudition, it is really difficult to think of any branch of knowledge which was cultivated at that time to which he did not have, with which he had not had very close acquaintance, be it medicine, philosophy, theology, jurisprudence, literary criticism, linguistics, and so on and so forth. Not to speak of the occult sciences, which were really very important for that time: astrology, elchemy, letter magic, and a number of associated disciplines, which he sketches very, very well with a lot of detail in his Muqaddimah.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 05:28

And The Muqaddimah started off as a kind of – Muqaddimah, actually in Arabic literally means a preface or an introduction, or a prefatory discourse, right – it was supposed to be a book that describes certain regularities that occur in history, things that have to do with the formation of political communities, with the formation of states, with the atrophy of states, with the dissolution of states, with the corruption of states and political systems, and that was supposed to be a kind of a key to assessing the variety of historical information to which he had had access. His main purpose being, as he said at that time, to write a history of North Africa, and to write a history of the two main peoples who were active in North Africa, namely Arabs and Berbers. And to that end, he composed the book, which starts with a discussion of historical methods of the way in which historical material, historical sources, may contain truths and falsehoods in why and in what way and through what kind of agency.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 07:19

He then followed this with a very, very long dissertation on the formation of societies, human societies, then the formation of political societies, the transformation of particular peoples into state making units, then the formation of states, the dynamics of state formation, and the kind of natural life cycle of a state, once it is established, and the way in which states then disintegrate as if by force of nature, and decline, as if by force of nature. And the discussion is, might be called, sociological. It might also be called political, but it is also economic, because he does discuss the way in which states manage economies, the way in which markets work, the way in which sovereigns try to influence market conditions.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 08:14

So we have that and then towards the end of it, about a third of the book is devoted to culture, because he thinks of culture, from his perspective, as actually essentially a craft. Culture is a craft. And the various disciplines that occur in a given culture, be it philosophy or carpentry, are all equally crafts, because they have social bearings. And they work as crafts, that is to say, with the acquisition of skills. Hence, he gets into a quite a detailed discussion about education, and the way in which skills are imparted upon students, be they studying theology, or medicine, or any of the artisanal professions that were at that time available. That really is in sum, in summary the overall picture.

John Torpey 09:11

Yes. I mean, and it’s a fascinating book that, you know, both refers to and reminds me, at least of you know, Aristotle’s Politics. And, of course, it’s been long known that the Arabs were crucial to transmitting the culture of ancient classical Greece to us, you know, moderns and I wonder if you could talk a little bit about his relationship to that culture, and the extent to which we might see him as kind of a bridging person, you know, between that world and ours?

Aziz Al-Azmeh 09:49

Well, I’m not sure that he’s a bridging person because the curious thing about him is that when he died, there was very little reception of his work. Very little reception of his work until the 19th century. Except for one particular aspect, you see, some passages in The Muqaddimah might be taken as books of advice of political advice. Fuerstenspiegel type of attitudes. The Ottomans in the 17th century had the book translated into Turkish, and thought of it as a kind of manual of statecraft, right, which in fact, it is not. But anyway, that is the way they understood it. That apart to address the question that you asked me, he was very well versed in Aristotelian philosophy, particularly by way of Avicenna, Ibn Sina in Arabic whom he had read very, very carefully, indeed.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 10:51

And the way in which Aristotle is present in The Muqaddimah is in the overarching concepts that structure his arguments: potentiality, actuality, the notion of nature, the notion of nature as a predetermined form of movement over time. Some of these, the notion of substance and the notion of essence, these are really implicit in the main concepts that he generated, so he actually structured his arguments in terms of Aristotelian natural philosophy. And he compared the state, or he conceived the state on analogy, with natural bodies, conceived in medical terms, which can take quite a lot of the Aristotelian physical input as transmitted by or developed by Avicenna, right?

Aziz Al-Azmeh 11:44

So it’s really quite an extraordinary feat, to use philosophical concepts and in a context with which they were not normally associated. And that is one of the very, very interesting twists, if one were to read the book really carefully, and look at the structure of arguments and add the logic according to which the natural life cycle of the state works. So the idea of organic analogies is really quite crucial there into the understanding the thought of, of Ibn Khaldun. The book is also philosophically very, very well informed. There is a large chapter on philosophy, particularly on Arabic philosophy, there’s a little bit about Aristotle, but mainly about Avicenna and Al-Farabi. And much less than one would think I would think he would have written about Averroes/Ibn Rushd, but he was really very much in command of the discipline, which he was able to use very creatively.

John Torpey 12:52

Fascinating. I mean, I guess I’ve always sort of understood the book, in some ways, as organized around this notion of (I’m going to mispronounce it, but) assabiyah, which I think could be, you know, satisfactorily translated into English as solidarity, or something like that. And so in that sense, there does seem to be a kind of at least anticipation of some of the central ideas of of Emile Durkheim, and his concern, which I think centrally was about the idea of solidarity in human societies where it comes from how it changes, etc. And it seemed to me that Ibn Khaldun was also very much concerned with the extent to which different kinds of societies could generate, you know, the assabiyah, that was necessary for their continuation and success. So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 12:56

Of course, of course. Assabiyah is quite often translated as corporate solidarity or the solidarity of a group, usually understood as a sentiment. Of course, assabiyah is a sentiment but assabiyah also designates a power group, a power group which is welded by an internal cohesion and internal loyalties. So assabiyah, is, in essence, as he says, comparable to a genealogical relationship to a family, it doesn’t have to be an actual family, but it acts as if or it functions as if it were a family. That is what al assabiyah is. So, the power of a state is actually obtained by al assabiyah, which then manages to overpower others and come on top and then found a dynasty. Once the dynasty is founded, then another type of process enters. There’s a phase of prosperity, and expansion, followed by longer phase of decline and obsolescence and the replacement of one power group by another.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 15:07

So assabiyah is really a power group, not simply a sense of solidarity. It’s a power group, which is also internally animated by a feeling of solidarity, which is analogous to the solidarity among members of a family. That is how it functions. Now, there is empirical purchase to this, very clearly empirical purchase to this, and many of the developments of the long passages in the book, which talks about assabiyah, and the way it acts in a state, and founds the state and transforms itself in the process of rule are sustained by very clear reference to empirical material. Material things that he had seen and witnessed himself and what the histories that he read had taught him about the way in which states had been founded.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 16:01

Now, the issue of he being an anticipator of sociological ideas is a very common one. Much of the 19th century scholarship talks about his affinity to quite a number of thinkers. Of course, you mentioned Durkheim, that is certainly the case with the idea of solidarity, but also, Ferdinand Tönnies, right? Of community and society for instance, that type of change that occurs under particular circumstances. This has been suggested many times. There are many comparisons that have been made with historians such as Herodotus or Thucydides, they idea of a pragmatic history, right. There have been comparisons with Machiavelli, comparisons with Vico, comparisons with Durkheim, comparisons with Hippolyte Taine, then quite a number of course, comparisons with late 19th century German theories of the state, of the power of state, right. And theories of the elites and elite transformation or elite formation and so on.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 17:11

Now, these, to my mind, there is always a certain anachronism there. Bringing a 14th century, a body of 14th century ideas, and comparing them with ideas that emerge several centuries later is to my mind, in principle, a little bit difficult. One can certainly present quite a number of analogies, whether that amounts to precedence is another matter. There cannot be precedents, because there is no line of transmission between Ibn Khaldoun and let us say, Durkheim, or Ferdinand Tönnies, or Gumplowicz, with the theory of the state, there is no particular line of filiation, as it were, there is no line of filiation. So the idea of an abstract anticipation in a previous age is fair enough that can be said of Ibn Khaldun, it can be said of many others.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 18:11

And incidentally, I from time to time, I do give students, graduate students a reading course of The Muqaddimah, when we read the various extracts from it. And I usually ask them to pick one particular thinker and see if there might be any meaningful comparisons with Ibn Khaldun. And I’ve had many, I’ve had many, many suggestions and many papers have been written. John of Salisbury, Rousseau, and really, Thucydides, and quite a number of others. And there is literature on all of these things/ The literature on Ibn Khaldoun is vast, there’s a huge literature on him, starting from the 19th century, and particularly 20th is very rich. Quite often you will find that these comparisons are fairly approximate and not very professionally done. But sometimes you will find a certain effort at highlighting conceptual analogies, which really do work. Now what the value of these comparisons is, I’m still not entirely certain. What would the value be of a comparison between a certain concept of the 19th century regarding society and something which may bear certain similarities to it, 500 years earlier. I don’t see where this would take us.

John Torpey 19:38

I understand. But I mean, you know, the way you’ve described him, and the way I also understood him is as you say, as somebody who could be seen as you know, a political thinker, or somebody who could be seen as a social thinker or an economic thinker. I mean, and you find all of these elements, it seems to me, in Aristotle’s Politics notwithstanding the name, the title that it’s been given in English. You know, it can includes all of these things. It also includes military organization, the idea of citizenship, how you should organize cities, all these all these issues about human life.

John Torpey 20:21

And, you know, in that sense, you know, neither neither Aristotle nor Ibn Khaldun anticipates today in the sense that they were sort of universal thinkers about human life and its organization very, very broadly. And if Weber is right, that the modern world is really about specialization, you know, they don’t fit into it. But I do see, you know, a sort of significant continuity or whatever it is, from Aristotle to Ibn Khaldun. But this then raises the question of, you know, the extent to which The Muqaddimah speaks to our world as opposed to primarily the Middle East, in other words, not a historical but a kind of comparative dimension or question here.

John Torpey 21:15

And, you know, one of the things that struck me about the book is the kind of argument that he makes, if I understood it correctly again, about the way in which, nomadic desert societies are sort of tough, because they have to be, and sedentary societies are on the road to, you know, decline. I mean, it’s a kind of a argument, I suppose we’ve seen, you know, over the centuries in the past, and to some degree, I suppose, in the present. But it speaks to, you know, a set of concerns, which in some ways, we’ve transcended, I suppose, by our relative control over the environment and that sort of thing. So I wonder whether, you know, to what extent would you say this book really kind of is relevant to our world? Or, particularly relevant to a particular part of the world and perhaps a particular time?

Aziz Al-Azmeh 22:08

It’s a very interesting question. Let me let me see how best to – I mean, one can speak about this for at very great length, let me see what the best economy of the answer might be. First of all, just one comment on Aristotle, whom you’ve invoked several times. Ibn Khaldun does have a very rough theory of political forms. Aristotle was preoccupied with the forms of polity much more directly than Ibn Khaldun. And with the transitions between various forms of political organization with a certain prescriptive preference, right? What one does find in Aristotle, one does not find this in Ibn Khaldun. The only typology he offers his one between political systems based either in reason or in revelation, which are for the public good and which are mindful of the common weal, and the arbitrary rule of irrational kings and princes, which are destructive of the social fabric and destructive of the dynasty in which they rule. That is the only typology; it’s a common one. It’s an interesting one. But it’s not directly pertinent to your question, but it’s an important prefatory point.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 23:40

Now, the way in which he speaks to the modern world is various. There is, on the one hand, this idea of, and this is a very common idea, it’s not specific to him, but it does come through with him with peculiar elegance, with particular elegance and force, the idea of the softness of civilization. People in our more primitive condition are tougher, healthier, and more moral than those who have been corrupted by ease, and by plenty and by the exercise of unlimited authority over others. This is a this is a very, very common theme throughout the book, from the beginning to the end in a variety of contexts. So, the idea of a kind of primitive idiom of a human society, which is content with what it has and with the limitations of what it possesses, and of what it can dispose is a mark of great admiration.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 24:44

But then, there is added upon this a certain tragic attitude that these will in time or with time, transform themselves into forms of rule. They will make themselves into dynasty, or subsidiary dynasties, and they will enter into a logic of corruption. So the idea of generation and corruption – the Aristotelian idea – is very much present also in this disquisition on the nobility of the primitive, and the softness and ignoble character of those who have had times of prosperity. So there is that particular sentiment and a particular sentiment which might actually speak to some of our friends who have greater who have direct and continuous concern with issues of sustainability with issues of environmental justice or justice to the environment as it were, you might have.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 25:44

He would also speak to us on the ubiquitous thesis of the way in which power corrupts. The actual exercise of political power corrupts, right? Lord Acton’s famous dictum of the 19th century: ‘power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ right? It’s very much in the same spirit, as the overall structure of Ibn Khaldun’s arguments about the structure of states and the constitution of states, and the inevitable atrophy of states as well. So he really does speak to us in a variety of ways: The detailed arguments about the ways in which solidarity groups behave in a city; the way in which competition, as economists would say, competition is distorted with the intervention of the state in commercial activities; the idea of the debasement of currencies and the way in which currencies might be debased by deliberate or in deliberate action by state authorities in a given situation. These are all things that speak to us and speak to us very directly.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 27:00

Actually, most importantly, to my mind, The Muqaddimah is simply a stupendously important book. It’s a great book, it’s written very beautifully. Incidentally, I’m afraid that the the standard English translation really doesn’t come up to the standard of the original work, which whose language is limpid, elegant, highly metaphorical, fairly complex, yet clear. The translation is very elementary with indications that much of the subtlety of the original is actually lost in the English translation, unfortunately. So there’s quite a lot of quite a lot of distortion, including the overall use of the word nomadic, because, but that were to Ibn Khaldoun is not simply nomadism. It’s all it refers to all forms of life outside cities. So villages, agricultural communities, not only nomadic peoples, transient, but all non-urban forms of social organization, he calls bagawa, which the English translation conveys, as nomadism and nomads, which is really quite cognitively very dissonant, if one knew the origin.

John Torpey 28:26

All right. Got it. So, I wonder, you know, you’ve talked a bit in the course of our discussion about the reception of the book, and, you know, the question whether it’s known or well known or not, and I wonder if you could say a little bit about, you know, your understanding of where it is, you know, currently being read and where it isn’t, and, you know, what are the chances that in those places it isn’t being read that it might be again?

Aziz Al-Azmeh 28:54

Well. First of all, there are a number of books which I personally regard as, as fundamental for the, for certain conditions of literacy, right? And this would include The Muqaddimah. It would also include Herodotus, it would also include Machiavelli, and really quite a number of books which are very well known and very wide, very widely known and little read. There are books which are often mentioned, authors who are often mentioned, but not usually read or read with sufficient attention and deliberation. So it belongs to a pantheon of books that must be read by literate persons, that as far as I’m concerned, that’s number one.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 29:41

Secondly, all histories of historiography will need to involve a reading of certain passages. All histories of the social sciences need to include some of his chapters. All histories of political forms need to include some of his thought, and I mean, some universities have courses in all of these fields in which students do read one or more chapters of The Muqaddimah, or even less than one chapter. It’s a very long book. And certainly, of course, anybody who’s interested in the history of the Middle East needs to read this book, because it is very telling in a variety of ways. It’s astonishingly rich, really astonishingly rich, and very suggestive. I personally, I wrote a doctoral thesis on Ibn Khaldun’s reception actually, that was my doctoral thesis. After which I wrote a book about a reinterpretation that’s 40 years ago nearly now. But I come back and read the book through, every now and then I dip into it every three or four years, I read it through, because it is really it’s such a delight, I must say. It’s a delight to be in the company of a of an author, who is so intelligent, so keen, so very perceptive, and covers so many, so much ground as well.

John Torpey 31:00

But well, you and I agree about the significance and and appeal of the book. But as I say, you know, concretely, where is he known? Where is it read? And where’s it not being read?

Aziz Al-Azmeh 31:14

It’s read, as far as I know, it is read in university courses on the Middle East, on the history of the Middle East, particularly, right, not as a main not as a main component, but it’s often offered as an optional course in courses about the history of the Middle East. And it is included in some of these general civilization sequence courses, which would start with the Epic of Gilgamesh and go all the way through to Hegel, Marx, and beyond.

John Torpey 31:45

Right, but is that in the US in Europe?

Aziz Al-Azmeh 31:48

Well, at least in the US, actually, I have seen it in some curricula in the United States. I cannot tell you where, because I really haven’t looked at this recently. Most certainly, it forms a component in the similar sequences at American universities in other places, for instance, the American University of Beirut, which has a civilization sequence compulsory to all undergraduates, the American University of Cairo, which has a similar kind of course. All of them, you know, inspired by the Chicago and Columbia models, right. So yes, that’s, that’s where it is.

John Torpey 32:30

Okay, well, hopefully we can give it some attention that much deserves.

Aziz Al-Azmeh 32:35

I should hope so very much.

John Torpey 32:38

I want to say that’s it for today. I want to thank Aziz Al-Azmeh for sharing his insights about Ibn Khaldun and The Muqaddimah and his understanding and contribution to world history.

John Torpey 32:53

Remember to subscribe and read international horizons on SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Hristo Voynov for his technical assistance. This is his swan song and we’re going to miss him. I also want to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for this show. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.