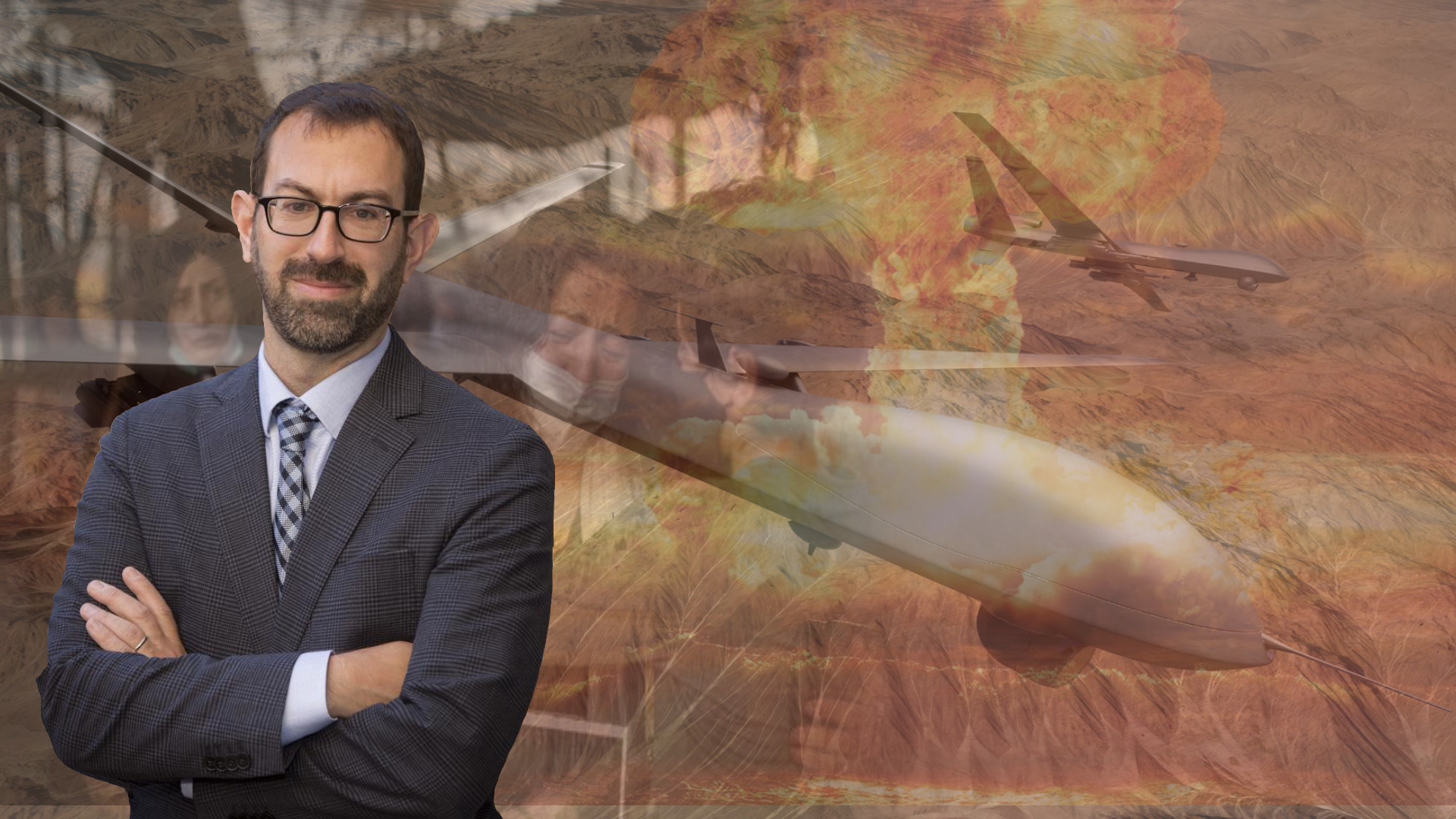

Do Humane Wars Lead to Forever Wars? with Sam Moyn

Have efforts to make war ‘humane’ made it easier for the United States to undertake military action? How do those efforts balance with efforts that are instead aimed at peace? What can we expect from the laws of war in the future in the face of changing technology that replaces soldiers with machinery?

Samuel Moyn, Henry Luce Professor of Jurisprudence at Yale Law School, discusses his new book, Humane: How The United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War, with RBI Director John Torpey.

You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud below. You will find a transcript of the episode here or below.

Transcript:

John Torpey 00:05

The Geneva Conventions and other measures have sought over the past century and a half to impose on war greater legality and restraint. While these laws of wars, the Jus In Bello, have been increasingly codified over the past several decades, the constraints on waging war itself, the Jus Ad Bellum, have not necessarily kept pace. If war fighting has been made more humane, has that made it easier to make war, especially in the United States?

John Torpey 00:37

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast to the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m Director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Today we discuss these issues with Samuel Moyn, author of the recent book Humane: How The United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War. Samuel Moyn is Henry R. Luce Professor of jurisprudence at Yale Law School, and professor of history at Yale University. He’s written several books in his fields of international, or European intellectual history, and human rights history, including The Last Utopia, Human Rights in History, Christian Human Rights, and just before the current book, Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World. Over the years, he’s also written in venues such as the Boston Review, Chronicle of Higher Education, Dissent, The Nation, The New Republic, The New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. Thanks so much for taking the time to be with us today. Samuel Moyn.

Samuel Moyn 01:51

It’s a privilege. Thanks for the invitation.

John Torpey 01:53

Sure. Great to have you. So let’s launch right into we’re basically going to talk about the new book today. So Humane argues that making war less brutal may also make it easier for the United States to get into wars. And I think you also suggest that opposing brutality and war is a kind of distraction from the real problem. So the signature line here is “we fight war crimes, but have forgotten the crime of war”. But are these things necessarily mutually exclusive?

Samuel Moyn 02:24

Not at all. And that’s why I wouldn’t want to see the attempt to make war humane as a distraction. I just think it poses a risk. And I got interested in the topic because it’s self evidently a good thing to have less brutal war, rather than more brutal war. And it’s incredibly honorable that generations have struggled with relatively paltry success until recently to get that job done. But what I wanted to investigate, since it has become so vivid in our own recent American history, is this risk.

Samuel Moyn 03:03

And so my general view is that we can walk and chew gum at the same time, it’s just we haven’t lately; we’ve humanized American war, and as it’s been unleashed, to become increasingly endless in time and unlimited in space. And it’s not just window dressing, because I think the moral project has changed the form of war. And so it’s the book is intended to be a call to control a risk, not to stop a noble project, but to recognize what kind of collateral damage it itself can cause to what ought to be our highest goal, peace.

John Torpey 03:45

I see. I mean, it seems to me there’s certain continuity with the approach you take in Not Enough, that is, with the idea that there’s something in a certain sense good going on, but it may also be distracting us from something else that may be more important. In that case, to do with economic equality, that the focus on human rights was a distraction –if I can use that word– a larger concern that seems in many ways to have been more important or at least perhaps neglected during a time of growing inequality in the United States and many other places in the world.

Samuel Moyn 04:28

I mean, I get that it sounds parallel. And it’s certainly true that I’m holding out for something better in both cases, but I personally would distinguish the book and characterize neither one in terms of distraction. The argument about human rights, including the very belated attempt to build in economic and social rights, in the prior book you mentioned, Not Enough, was, in a sense, easier on the human rights movements and the global legal frameworks that have been built, because in that case that the suggestion is just that it’s a minimalist and selective project that has survived as prestegious in a neoliberal age, precisely because it’s just interested in building a floor of of sufficient protection when it comes to the basic decencies of life, housing, food and so forth, while other forces in the environment are obliterating any ceiling on inequality. And so it’s really just a story of parallelism not of complicity or even distraction. It’s calling on not the human rights movements to stop what they’re doing or even change, but on the rest of us to understand that it’s a minimalist partial project.

Samuel Moyn 05:57

In Humane, the claim is, I think harder, because I think we have seen, especially in the presidency of Barack Obama, actual legitimation. And we should always remember that law and legal discourse isn’t just about constraining or stopping, but also about legitimating and permitting. And in this case, the laws of war in their new humane form, have, in a sense, helped rationalize, for a lot of people –and we can get into who those were– the continuation of war. And so in that case, I am arguing for a lot more blame. And that’s why I say there’s like a risk in the laws of war in this new form, which we ought to control better, because the risk can actually have negative consequences. Not just kind of fail to get everything done we can imaginably want our agendas to cover.

John Torpey 06:59

I mean, okay, I get that, you know, you’re sort of reluctant to use the term distraction and I hear that. At the same time, I sort of wonder it seems to me a lot of contemporary left politics are about whether one thing isn’t a distraction from the other, race, you know, as a distraction from class, for example. And so, so I’m thinking maybe about distractions.

John Torpey 07:22

And one of the other perhaps distractions that came to mind as I read the book, was something that Mahmood Mamdani raised during the Iraq war, and that was the massive sort of preoccupation of American whatever, progressives, with genocide or putative genocide in Darfur, at the same time that something that they could do frankly little about, while their own government was, you know, engaged in a massive conflict in Iraq, where many, many Iraqis (if perhaps relatively few Americans) but many, many Iraqis were dying. Is that the kind of thing that we should also be worried about.

Samuel Moyn 08:11

So first, a word about distraction, and why I avoid it, because it seems to suggest a kind of causal argument that if we weren’t doing one thing, we would do something else. And it’s just incredibly hard to establish that. Whereas in Not Enough, I’m actually trying to avoid that kind of claim by saying, look at just what human rights are trying to do, relative to this other agenda, namely, more distributive equality that’s neglected.

Samuel Moyn 08:51

That doesn’t imply that we stopped at doing the one thing in order to do the other. It also doesn’t imply that doing the one thing is keeping us from doing the other because we could just have higher ambitions. In this book, Humane, I avoid the notion of distraction because I’m not even trying to prove that if we weren’t paying attention to the laws of war, we would care more about peace. Because at any rate we don’t want to stop trying to get war to be more humane, we want to do the other thing.

Samuel Moyn 09:31

The reason I said I’m harsher in this case is because it’s clear that Barack Obama and others actually tried to appeal to our power to validate their wars by assuring us that they’re humane. And so legitimation is different than distraction. And I think I show that legitimation happened, at least Barack Obama wanted it to happen because otherwise why would that be the central focus of his Nobel address or his drones address.

Samuel Moyn 10:07

Now on Mahmood Mamdani, you know, he’s a great scholar. I hear that as a claim about hypocrisy in the first instance, and if that’s what the claim is, I’m on board. I think there’s some, there’s a similarity. And we can get into this because, in my account, my kind of hero in the book, Leo Tolstoy, definitely makes claims about the hypocrisy of audiences who trust in the humanity of their wars, even when they’re kind of the wars themselves are doing so much damage, even when made more humane.

Samuel Moyn 10:53

If Mamdani meant something stronger, that all those young people with the viral videos on YouTube, and so forth, who wore Save Darfur bracelets, were actually abetting American warmaking or distracting us from it, I think that’s incredibly hard to establish, and he probably didn’t. And so that’s why I really just want to insist that we get clear on what the claims are, rather than kind of oversimplify them, because in order to make them seem flimsier than they actually are.

John Torpey 11:33

Got it. So I mean, I think in general, there’s a kind of desire in the book, reflected in the book, that basically, we live in a world without war or that we should think more about the world in those terms. Right. So I wonder this is obviously a long term dream of the human species that this kind of conflict could be eliminated. One that however, it seems perpetually disappointed. So I wonder if you could sort of talk about how you see the hope of a world without war.

Samuel Moyn 12:15

Excellent question, John. You know, the stance I try to take a stake out in the book is what I call an anti-war stance, which I distinguish from a pacifist one. And the main idea that of the anti-war stance is that most wars make the world worse. And even if we expect otherwise in advance of at least some of them, it regularly turns out to be the case that they set us back, and not just those who suffer their ravages, but those who wage them. And I think there’s an increasing American consensus in just recent years that has been true of many aspects of the war on terror, considering the politics around the Afghan withdrawal.

Samuel Moyn 13:10

I have a somewhat bolder view that I can’t find an American war fought in my lifetime that was worth it. And so if the book is written from the kind of perspective that we could imagine one or two or three or four fewer wars. I narrate in the book that it was astonishing that in modern times, it could be credible to diminish the incidence of war and the idea that it could, aside from at the end of days as in the promises of biblical prophets, was new, and it has about the same birthdate as the whole idea that we could end chattel slavery, or that we could end grinding poverty. And what I tried to narrate is like what reformers did to try to make progress on this.

Samuel Moyn 14:12

That’s, you know, while you’re right in your intro, that I definitely pay most attention to, the legal history of the Jus in Bello of making war more humane eventually. I tried to give equal attention to the the fortunes of the Jus ad Bellum which has reduced the incidence of international wars. I tried to point out the irony and paradox that the first and central cause for a long time was providing a European peace. And the irony and paradox was that America actually signed up to provide it at the end of World War Two, but it came at the price of endless and repetitious global wars of the kind that America hadn’t fought to that point.

Samuel Moyn 15:01

And so, I’m interested in what could we imagine further constraints? And, one central narrative is the the abuse of the rules that are supposed to constrain force and keep wars from happening in recent decades and tell a story in which, as a result of activism and public focus, those rules have gotten short shrift, even as the rules that are supposed to constrain the fighting and make them more humane have gotten intense interest and been at the absolute center of public debate, insofar as there’s been any around the war on terror.

Samuel Moyn 15:44

And so you don’t have to be like a misty idealist to think that peace is worth striving for not as an all or nothing, but as a matter of moving a little bit down the continuum fighting one or two or three or four fewer wars that not only are grievous for civilians, but for soldiers themselves, the publics to fund them, the states that we set back as we did Afghanistan in a 20 year waste of time and loss of life. And I think we can extend that to you know, many other wars past and likely future, alas.

John Torpey 16:25

Right. So I mean, you said that there hadn’t been a war in your lifetime, or at least your adult lifetime, that had been worth fighting. And it leads me to ask something I also thought about when I was reading the book, mainly, you know, to what extent are these wars that you’ve been getting into misguided as a result of the fact that Congress hasn’t been really on board to do its job and to declare war? And that basically, wars are a matter of executives deciding to carry out things that they think are a good idea, which might not be if Congress really were living up to its responsibility?

Samuel Moyn 17:09

You know, it’s a it’s a fantastic question. And I really think that it points to a very significant front for action and thought. And I’m very much in favor of more attention to Congressional abstention from war and peace in its constitutional role, and actually a lot of other matters. But I think we should recognize that there’s a little bit of kind of missed direction that Congress plays. It’s, first of all, it has passed expansive authorizations. And we can argue that the executive has done things beyond its remit. But the fact is that it even if we want to say that the President has abused his authority or claimed article two authority or whatever. In a way, the trouble is that Congress did authorize a lot. And even if we think that the President’s been abusive, which is is true, we should also acknowledge that Congress has read into these actions, it funds them through appropriation bills, and it could easily turn off any war or war in general.

Samuel Moyn 18:36

And so I think, you know, we should really think about the incentive structure that Congressional representatives face. And it’s really less about being involved in the war, which they want to avoid, as so much as the appearance of it and shirking responsibility at that level, even while they get together for annual rituals of funding defense at increasingly higher levels. Amazingly, the two parties which are at one another’s throats, in the midst of the first impeachment, like just took took an hour to go vote through almost unanimously that year’s National Defense Authorization Act at, you know, incredibly high levels of funding that we could do something else with. So it’s not like I think Congress doesn’t need attention.

Samuel Moyn 19:30

I would say, and I focus in the book much more on let’s say militarist ideologies, beltway expertise, which I think at both before and after the end of the Cold War, favored war, and made it seem like it was worth doing much more often than turned out to be the case. And that’s why I’m heartened by developments, both on left and right that are beginning to question kind of American militarism. And I would say Congress is — Congressional members are people too –and the trouble is that they’ve been part of a kind of intellectual syndrome as much as they’ve been part of a kind of political one.

John Torpey 20:16

Right. Well, this is interesting, because the the next question I wanted to ask was whether you think Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan signals anything, you know, important in the kind of direction that you are hoping things will go? I mean, you know, it’s well known, I think that he’s been opposed to the Afghanistan involvement for a long time. And so in some ways, I suppose Trump, in a way gave him an opening to do this, and it was a bit of a mess. And there’s still people who are, there many people now who are exposed to the the rigors, shall we say, of Taliban rule. So it’s not ideal, but neither were the 20 years that we spent there. So just, you know, what do you think this may portend for the future?

Samuel Moyn 21:05

I think we can see now that Biden was the third in a series of presidents who were elected as anti-war candidates, at least selectively. Obama won first against Hillary Clinton as someone who hadn’t supported, or at least at the beginning, the Iraq war, and Donald Trump emerged against his fellow Republicans, amazingly, for denouncing the Iraq War, which was taboo at the time, and then won against Clinton again. And I’m not suggesting that he was an authentic anti-war voice, but I think especially amongst veterans, he gained a lot of electoral support from saying he was. And then Biden came out against the forever war in his campaign. And I think that’s an that’s an encouraging development. The trouble is all of the above, running as endless as anti-war candidates have ended up endless war presidents.

Samuel Moyn 22:19

And, it’s too soon to tell with with Biden, but in a way, he just followed through on the trend, for which I argue in the book, away from a heavy footprint interventionism towards a light and no footprint, surveilling shadow war. And in his speeches defending the Afghan withdraw, Biden promised to keep that one going. And so in some respects, he’s purifying, I think, the incredibly frightening move that we’ve seen in the last 20 years, which is to respond to an originally brutal and heavy footprint and visible form of the War on Terror by slowly inventing a humane and light, no footprint and less visible form of it.

Samuel Moyn 23:24

And does it mean that it’s better than the alternative? I think so. Unless the alternative is not having that new form of it, either. After all, what’s been involved in it is, is just an extraordinary assertion of American and executive power to assassinate in space, in lots of new places, practically anywhere and in time forever. And I think we would have rejected those extraordinary assertions in the past, because it involves a power that no government should have, and in a world where great powers rise but inevitably fall, and precedents are set. So now targeted killings have been normalized for the global future. And that’s our bequest as Americans to world history. And I think that’s a great tragedy. It’s not one that Biden is probably going to try to convert into a happier ending, I’m afraid.

John Torpey 24:31

So this is where I thought the book was, perhaps especially pessimistic. I mean, it struck me as I read this line, that maybe I compared this book a little bit to Not Enough. And it seemed to me that this had if Marx was the patron saint of Not Enough, Foucault, this has a more Foucauldian kind of sensibility. And I want to quote one line in which you say “today’s deterritorialized in endless war may mutate into rule and surveillance by one or several powers across an astonishingly large arc of the world’s surface patrolled by armed drones, or paid visits by the special forces acting as quasi-permanent military police.” I mean, is that I think you’ve just said, this is kind of where you think we’re headed. Can you say a little bit more about that?

Samuel Moyn 25:32

Absolutely. So I mean, I think we can be influenced by these great thinkers without being their slavish disciples. And, again, I was making a modestly social democratic case in Not Enough. Social democrats were influenced by Marx, develop their own egalitarian views. And I think, you know, Marx’s critique of human rights was much more pitilous than mine. In this case, obviously, it’s deeply influenced by Michel Foucault and I actually opened the book with a tale of two weddings, which is supposed to mimic the opening pages so famous of discipline and punish where he compares the dismemberment of a regicide in France before the French Revolution, a brutal dismemberment, with the kind and gentle domination post-revolutionary prisons and worries that things might have gotten worse because now it’s not the body that’s in the crosshairs of the state, but the the soul, as one of Foucault’s French predecessors, Alexis de Tocqueville, had originally warned. I think that’s happening on a global scale. But the jive that so many have made against Foucault, and that I share, is that he was a pessimist who hid any normative defense of his ideals or made them unspoken.

Samuel Moyn 27:17

And so, my use of Leo Tolstoy is meant to kind of remedy that error and give us some optimism. I do identify with Foucault and Tolstoy — you know, domination, not necessarily violence, as the central evil in human affairs — and with a lot of others, and in so-called republicans (small r tradition). But by suggesting that, you know, while peace doesn’t mean justice, more peace in our world, at least great power peace, could mean more global justice, or head down that road, in small steps of one less war, two less wars, three less wars. We really could imagine developing a criticism of this new form of domination and control and surveillance that we’ve invented as the new form of counterterror. And so I want to make use of these more ruthless critics, while also trying to save a reform project from the the kind of radicalism of their critique, for us to be able to countenance and therefore give ourselves some hope and optimism for how we could escape the syndromes that they were so brilliant at depicting.

John Torpey 28:49

Well, I hope I didn’t characterize you as a slavish follower of any of these people. But I was struck by the kind of Foucauldian influence and I was also intrigued by your answer by the fact that I’ve always wondered whether anybody else noticed that Tocqueville had said this about governments getting in people’s heads rather than at their bodies. I have a long time ago.

John Torpey 29:13

But in any case, one, perhaps, last question. And that is, I guess, about the role of technology in all of this. I mean, as you know, to me a lot of what’s happening is a shift to technologies that there’s a lot of debate among in military circles, ethical circles, about how much freedom can machines be given to conduct our wars for us. And certainly imagine if you’re a soldier, liking the idea of a robot, you know, being out there potentially taking the bullet rather than yourself. But obviously, this raises huge ethical questions and I don’t know whether you have as much to say about that, as you might, you know about the process of war in general, but it does seem to me that part of what’s happening is that, you know, technologically warfare is changing and becoming even more “dehumanised” than it’s been. So I’m wondering what you would say about that?

Samuel Moyn 30:23

You know, it’s a fantastic question. You know, I try to make technology central to the narrative all the way back by highlighting the rise of air war long before drones were the preferred mechanism. And by looking at the the tools of Empire, and of Imperial War that were fought earlier in the 20th century and back further, because they deserve a central place in the story.

Samuel Moyn 31:08

I guess my general take is that well, of course, technology isn’t, and technological change isn’t an independent force, and we need accounts of that, which I don’t try to provide. I’m struck by how our technology is, is morally speaking, us. We ask us, scientists and engineers for the kinds of tools that we would like for the kinds of wars we want to fight. And in earlier history, while there were some at the very dawn of the aircraft the thought that it would actually function to make war more humane, and that this was a good thing. Obviously, it’s, it was used without compunction for the most brutal ends.

Samuel Moyn 32:08

Not long after that, the American state asked for napalm. And it was invented for the sake of making war more brutal, not less. I think after Vietnam, which I present as this kind of the central pivot in the history of American war in this regard, not just the kind of audience in public, but significant forces in the military began to want more humane war. And I don’t think it’s just the case that someone came up with drones as part of the kind of linear history of just inventing things, rather, there was an end. A moral end that was becoming more legitimate and changing the potential future of war. And, you know, one thing was invented and deployed rather than another.

Samuel Moyn 33:51

I think that really matters with the rise which I close the book with the so-called autonomous weapons system, which are algorithmic rather than piloted in the way that drones still are. And, these robots are the future. And I think they’re kind of like the aircraft, they could have many different potentials. But it seems as if we’re already in a debate in which aside from the few abolitionists like me, when it comes to this tool, a lot of people want the programming to be humane. And indeed, we could imagine these robots as more humane than even drones have become, at least when you used per the rules.

Samuel Moyn 34:03

So, yes, certainly technology has exempted Americans and great power soldiers in general from immunity from harm. But there’s a limit when you’re dropping a bomb from the sky as drones do, or even when you’re visiting in person with special forces as we’ve begun to do more and more to how humane you can be to your targets. But we can imagine robots that are programmed to take prisoners, to capture rather than kill. We can imagine robots programmed to be like police that invites surrender which policing norms require, rather than kill on sight. And so I think that technology really matters, but it’s just an extension of our values. And I think we should study it in that way because that’s how it has functioned in the transformation of war in our time, I believe.

John Torpey 34:13

But these are fascinating issues that we’re obviously going to be engaged with for, I think, as far as the eye can see when it comes to trying to make sense of war and how we’re going to prosecute it insofar as we are, alas, engaged in it.

John Torpey 35:22

But that’s it for today’s episode.I want to thank Samuel Moyn for sharing his insights about war and war fighting and talking about his book, Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War. Remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Hristo Voynov for his technical assistance and to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.