India’s Struggle Against Covid with Manu Bhagavan

How did India go from declaring victory over covid in January to being the world’s hotspot 3 months later? As one of the largest pharmaceutical and vaccine producers in the world, did India focus too much on vaccine diplomacy and too little on internal vaccination efforts? How has India’s regional competition with China affected how this plays out?

Manu Bhagavan, Professor of history, human rights, and public policy at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY, talks to RBI Director John Torpey about how India reached its current crisis point and what other problems face today’s India on the international stage.

You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud below. You can also find a transcript of the interview here or below.

John Torpey 00:03

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that bring scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m Director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey 00:24

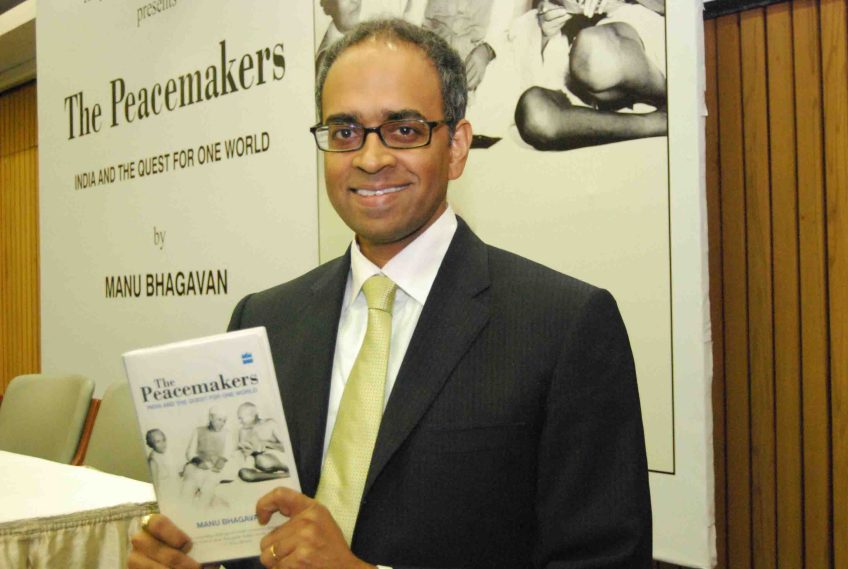

Today we discuss recent developments in India with my colleague, Manu Bhagavan, who is Professor of history, human rights and public policy at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, and a Senior Fellow at the Ralph Bunche Institute. He’s a specialist on the history, politics, and international affairs of modern India, and is the author or editor of many books, including most notably “The Peacemakers: India and the Quest for One World” which came out in 2012-2013. and “India and the Cold War” of which he was editor and came out in 2019.

John Torpey 01:02

He’s currently writing a biography of Madame Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, one of the 20th century’s most celebrated women, and someone who played a pioneering role in international diplomacy. Thanks so much for taking the time to be with us today. Manu Bhagavan.

Manu Bhagavan 01:20

Thank you for having me, John. And it’s nice to be able to see you and speak with you once again, after a long hiatus.

John Torpey 01:28

Indeed, great to have you. Thanks so much.

John Torpey 01:31

So we’re hearing some worrisome news out of India in regard to the pandemic of late. It’s had now more COVID cases in a single day than the United States has had in its COVID experience. Although, of course, India is, of course, four times larger than the US in population terms. Still, things have definitely been getting worse in India. And what’s happening there is leading the larger series of surge of cases around the world. So can you tell us what’s going on?

Manu Bhagavan 02:02

Sure. Well, as you just indicated, India is in the midst of a COVID surge. According to experts, this is India’s second major surge of COVID. For which, it appears, it was utterly unprepared.

Manu Bhagavan 02:22

So just a quick rundown of where things stand at the moment. As of yesterday, India was running over 300,000 new cases per day. And those numbers are increasing with each day, and over 2000 deaths per day. However, again, as you pointed out, by percentage terms, compared with the United States this is overall lower considering the size of India’s population. But these are reported numbers and experts have concluded that there is severe under reporting or misreporting throughout the country.

Manu Bhagavan 03:02

And that actual figures could be as great as anywhere as 10 to 20 times as great as the stated figures. So for example, Time magazine ran an estimate that potentially as high as 400 million people are currently infected in the country or about one-third. But I’d say we can sort of talk about a range of projected cases using reported plus unreported of somewhere in the range of about one-fifth to one-third of the population currently being infected.

John Torpey 03:42

Sounds pretty serious. And I’ve also seen reports to the effect, basically saying something that happened, apparently, a year or so ago as well in the early days of the pandemic, and that is that significant numbers of people who were essentially migrant workers in the cities were concerned about the lockdowns.

John Torpey 04:05

I mean, Modi’s initial lockdown in March-April last year was very famously very severe. And a lot of people just fled to the countryside because they were afraid they would be without a way of surviving, essentially, if they didn’t go back to the families that they had left behind in the countryside.

John Torpey 04:24

And of course, the problem with this in epidemic terms is that they may be taking the virus back with them to their villages and to the countryside from which they came. So, can you say a little bit about, I mean, it seems like a kind of very important case of the kinds of economic effects that these shutdowns and lockdowns have on populations in the world that don’t have a lot of economic alternatives. So how would you say this has affected the economy and the wellbeing, I mean, leaving aside kind of the pandemic itself. How have the government responses affected the population of India?

Manu Bhagavan 05:16

Well, the news overall is bleak. Before I answer that, I think I should just give a little bit more setup, which is that, India during the first wave, its initial response when COVID first came out was, as you just indicated, to impose a draconian lockdown nationwide. And that came with very little notice. So part of the problem with the lockdown was not so much just that there was a lockdown, but how it was done within what timeframe, and how much flexibility or understanding people were given and what mechanisms were put in place to address various communities kinds of needs; which varied from community to community, depending on what kind of access they had.

Manu Bhagavan 06:03

And so the result of that was that, as you’ve indicated, there was a migrant labor crisis. And they were the ones who were primarily affected, that is to say, people from rural countryside, come and work in the cities. And when the lockdown was imposed, they had nowhere to go. And so they tried to flee back to their villages, they wound up packing train stations, they couldn’t get on the trains, and then they congregated there creating super spreader events, and then eventually took the virus back to the villages. And that made the first wave worse than it should have been or needed to be.

Manu Bhagavan 06:43

Now, that said, India’s whole experience with COVID has been extremely unique. So its first wave, which ran roughly until September of 2020, was less than many projections had expected, significantly less. And then, all of a sudden, in September or October, starting around October of 2020, the numbers simply plummeted. And then India became an epidemiological mystery; nobody really could come up with a real explanation. And subsequently, until this point, nobody has yet as well, which is that COVID seemed to miraculously disappear.

Manu Bhagavan 07:34

All kinds of explanations have been put forward: maybe it was the youth of the population; maybe it was exposure to other kinds of disease; maybe it was immune systems which were pumped up from other pathogens. It could have to do with low obesity rates. Anyway, all kinds of things were postulated as to the explanation as to why India’s numbers were so low.

Manu Bhagavan 08:01

But whatever the explanations were, there was story after story in the international press. By January, the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, sort of started chest thumping, and claiming that India had defeated COVID with its rigorous proposals and policies. And that the country had a lot to be proud of; not only had it defeated COVID, but that it was unique in the world, and that it had engaged national resources against the virus. And then people basically let their guard down.

Manu Bhagavan 08:41

Oh, I left out one important claim for the drop in the virus, which was there was a heavy mask mandate in the country, and people were adopting that significantly. After January of 2021, people let their guard down; they stopped wearing masks, they stopped social distancing, and they started large congregations again. And then on top of that, it’s election season, and there was a religious festival. And all of this combined has led to where we are right now.

Manu Bhagavan 09:19

In terms of economic impact, India has an extremely young population, and that young population needs jobs. So one of the bigger crises that the country had been facing pre-pandemic was how do you create jobs for so many people? And how do you sustain it, because they’re so young?

Manu Bhagavan 09:41

So you have to invest in all kinds of ways, and you have to create public and private sector positions to accommodate that many people. And there was a lot of controversy about what the government was doing to sort of spur that kind of growth. But subsequently — there were certain issues, obviously; there was a great deal of wealth generation in the country and has been for years, a number of people have moved out of poverty growing the middle class.

Manu Bhagavan 10:14

And so these were some success stories. There was also some overt changes in cities’ infrastructure, between cities and so on. But subsequently, from the pandemic, not only do we see a sluggish economy, but we see people falling out of the middle class in huge numbers, like one-third of the middle class has moved back into poverty in the last year or so.

John Torpey 10:39

As a result of COVID?

Manu Bhagavan 10:42

Yeah, well, as a result of COVID. And you multiply this by the previous lack of investment in jobs, or preparation for these kinds of things. And the country has set back significantly.

Manu Bhagavan 10:59

Now, I will say that some economic forecasts had projected that with the economic stimulus in the United States that India was one of the countries that was set to benefit in some ways from a global resurgence starting this summer. But right now, that no longer looks really viable. I mean, I’d say that the country is set back significantly.

John Torpey 11:25

That’s unfortunate. So one question is, how is the vaccine rollout going? I mean, my understanding is that the target number is something like 300 million, which is, of course, only less than a quarter of the population. And the point that you make about the youthfulness of the Indian population, I think, is also an important one.

John Torpey 11:48

I mean, it was conjectured early on, in the pandemic, that Africa because of the relative youthfulness of its population might emerge relatively unscathed. And I’m not sure exactly whether people think that’s actually been the case or not. And I’m trying to get somebody from the Africa CDC to talk about what’s going on there, who just put out an article in The Lancet on this.

John Torpey 11:48

But in any case, how’s the vaccine rollout going? Not so well, I gather? And are there the kinds of age restrictions that we have in the United States and European countries? Or how is it, you know, being organized?

Manu Bhagavan 12:29

Okay, so, India, is one of the largest pharmaceutical and vaccine producers in the world, thanks predominantly to what’s called the Serum Institute of India, which is based in the western part of the country out of the city of Pune in the state of Maharashtra. That isn’t the only place, but that’s one of the largest producers. And Serum Institute has contracted with a number of places to produce vaccines for India as well as for much of the rest of the world. India was expected to produce 60% of the vaccine for the rest of the world.

Manu Bhagavan 13:12

And Serum Institute in particular was contracted with AstraZeneca to produce the Oxford vaccine, the local brand name for it is Covishield in India. In addition, India indigenously developed its own vaccine “Covaxin”. And the trials for that also looked very good; that it was a highly efficacious vaccine.

Manu Bhagavan 13:40

And so on the face of it, India looked like it was positioned to do very well. It also has a long history of vaccine rollout and successfully vaccinating huge numbers of people. So in this interim period, where it looked like COVID was defeated, and India was set to do all of this with vaccine production, people really were grew very proud of the country.

Manu Bhagavan 14:12

And the Prime Minister sort of played up on that. And they engaged in what’s called vaccine diplomacy. They started shipping doses of vaccines to all kinds of other countries around the world who needed it; it was an act of generosity, and it was also an act of diplomacy, strategic diplomacy. And then the bottom came out.

Manu Bhagavan 14:33

So originally, the vaccine rollout was targeted at the elderly population as it was elsewhere in the world. And then they dropped the age limit to 45. That’s where it stands currently and those with certain kinds of conditions.

Manu Bhagavan 14:49

But the vaccine rollout was sluggish from the beginning, in part because people believe that the pandemic was over so they didn’t see any rush any need to go get it. And “Covaxin”, the indigenous vaccine, initially, the data regarding “Covaxin” was opaque. And so people’s confidence in exactly what it was or whether they would be mandated to get that was a bit low. And even with “Covishield”, people sort of had questions. So all of that combined with the fact that they thought that the pandemic was over led to a sort of sluggish response to receiving the vaccine; much slower than expected.

Manu Bhagavan 15:35

The Prime Minister did get vaccinated on camera. And that helped a little bit. But by and large, people responded slowly, and there wasn’t a designated campaign to really sort of get this going fast enough.

Manu Bhagavan 15:50

As of right now, about 10% of the population have received one dose of the vaccine, at least one dose, but only about 2% or a little over 2% are fully vaccinated. These are grim numbers. And now we have got a whole set of other problems.

Manu Bhagavan 16:09

So now, there appears to be a vaccine shortage. The country has announced that they’ll expand the age cap so that by May the 1st, everyone 18 and older will be able to get the vaccine when they wish. But the problem is that, as I said, there’s a vaccine shortage, and no one understands exactly where the things are magically going to come from in time.

Manu Bhagavan 16:39

This time, the Center has decentralized vaccine purchasing to the states. That’s leading to competition between states and raises questions about the ultimate cost of what the shots will be in the various states. So people claim that the current government is playing politics; it certainly appears that they very well might be. And so how they mitigate this is still up in the air. The plan originally, was that the vaccine would be free for everyone at all government clinics, and would cost no more than a small capped price at at any private clinic. But subsequently, we don’t know where things stand right now.

John Torpey 17:19

Is there a vaccine hesitancy problem?

Manu Bhagavan 17:22

It doesn’t seem like that’s a problem right now. I think people are sort of desperately ready for a vaccine shot. But at the moment, the bigger problem appears to be in production. Now Adar Poonawalla, who is the guy who runs Serum Institute, said that there’s a two part problem having to do with the United States, essentially. Which is that India needs some raw materials in order to be able to produce more vaccine.

Manu Bhagavan 18:00

Now this sort of has gotten confused in the press; people have concluded this means all vaccines. And I think he’s clarified very recently that “Covishield”, the Oxford vaccine, can continue to be produced. But there’s another vaccine in lineup, the “Novavax” vaccine. And for that they need more raw materials from the United States.

Manu Bhagavan 18:19

The Defense Production Act in the United States, I think, is what’s causing the problem, which is that US production has to be prioritized; US needs have to be prioritized through that. So they’re trying to work this out in a way where people can get the necessary stuff to India.

Manu Bhagavan 18:36

And the other problem has to do with additional vaccines. The US, for example, is sitting on a stockpile of AstraZeneca vaccine, which we’re highly unlikely to use. And so that’s something that could be sort of shipped out over there. And then there’s smaller things like Remdesivir, oxygen, PPE; these are things the country is in desperate need of again. It has indigenous manufacturing capacity, but right now the need is grossly outstripping its manufacturing capacity.

John Torpey 19:07

Right. Well, hopefully that’ll get addressed soon. And hopefully, the flow of vaccines to the other parts of the world will also get ramped up. We did a podcast a couple of months ago I guess now, about the importance of getting the whole world vaccinated. [The podcast] was based on a conversation we had with a couple of Turkish economists who had been involved in studying the economic consequences of that not happening; and they’re bad for us, as well as for those parts of the world where the people do not get vaccinated.

John Torpey 19:37

But let’s switch gears a little bit to what I think is really your kind of scholarly wheelhouse, which is India’s foreign relations. Many people including me in this podcast have been particularly attuned to the rise of China basically as the leading competitor, rival, whatever the proper term might be, to the United States, and to some degree to the West as such.

John Torpey 20:09

It seems to me that India and China have long had not exactly warm relations, not necessarily cold, but also often not the warmest. And sometimes sort of bleeding out over into conflict. And I wonder how you would characterize India’s response to the perception in the world that China is on the rise. Is India ascendant? Etc, etc.

Manu Bhagavan 20:40

Well, I’d say, India originally, dating back to its immediate post independence period, had hoped for very positive relations with China. They developed a five point program of peace famously, and talked about Indian-Chinese brotherhood. And things fell apart for a number of different reasons: having to do with Tibet; having to do with economic policy; and, bombast on the part of certain politicians and so on.

Manu Bhagavan 21:25

Anyway, this culminated in a war in 1962 where China invaded India. And then it looked like nothing was going to stop them and that they could march all the way down to Delhi. The United States was prepared to intervene, and then China just suddenly withdrew. So the effect was to humiliate India and the Prime Minister and reduce its stature on the international stage. And that subsequently put cold water on the relationship. And that lasted for a long period of time.

Manu Bhagavan 22:00

More recently, India had again tried to warm relations with China and was looking to forge partnerships and to look for common growth. Many people in India throughout the 2000s looked at China admiringly for its economic growth; for its incredible economic growth, the rapid development of its cities and technological advancement. And looked at it very admiringly and look to try to replicate that kind of success in India.

Manu Bhagavan 22:39

And then people in the West started raising some questions about what China was doing. And they postulated positioning India against China as a check on China’s growth. A lot of policymakers in India reacted against that and said, “No, India is no one’s pawn, we’re not going to be positioned against China. We can have productive relationships with everyone.”

Manu Bhagavan 23:10

And then two things happened. China launched this thing, the Belt and Road initiative, which was a global connectivity project. Global infrastructure but as a way to sort of build connections with all kinds of countries around the world. And India sort of hedged on that.

Manu Bhagavan 23:29

China looked like it was rising to the level of a global dominating kind of power, as opposed to partnering a kind of power. There was starting to grow some fear in Indian circles about that.

Manu Bhagavan 23:45

And then there’s been long simmering smaller land disputes between India and China, and those flared up recently again into, I’d say, a relatively minor military skirmish. But it sort of set the stage for the potential for more animus between the countries.

Manu Bhagavan 24:09

And then the pandemic hit. And the response in India, combined with all these other things, was similar to the kinds of things that happened in the United States initially, which is, there was a rise in anti-Chinese sentiment; predominantly against China as a state but the attendant racial, discriminatory beliefs have crept up with that as well.

Manu Bhagavan 24:38

And subsequently, there has been an ever growing suspicion between the two countries. And India, in the meantime, has partnered with some other countries into a new alliance called the Quad. The United States, Australia, Japan and India have forged it as a diplomatic partnership. And this is an important partnership, which some see as just generally strategic, but many people are looking at this through the lens of creating an Indo-Pacific Alliance, which, again, is read as a check on China.

Manu Bhagavan 25:21

From China’s perspective, this is unfair and that they’re trying to contain something that doesn’t need to be contained. And we’re seeing some potential realignments of, say, between Russia and China, and India and the United States. So things are in flux right now; there’s a great deal of concern in policy circles about where this could be headed. And I think it’s incumbent on everyone to try to cool temperatures as best as possible. I don’t think another conflict would be good for anyone.

John Torpey 26:00

Well, indeed. But one of the ways in which the region is in flux is that the United States has now announced this really finally definitively withdrawing from Afghanistan. And I wonder how you think that’s going to affect the local, the regional, kind of geopolitical calculus.

Manu Bhagavan 26:23

Afghanistan is complex. I think the United States is in one of these very tricky situations where it has gotten itself involved in this place, it has harmed it — in its involvement, it has caused some harm. But obviously, this is a place that has had, and before US intervention, additional problems with the Taliban as a base for Al Qaeda and its borderlands with Pakistan. And that it’s suffered from terrorism significantly.

Manu Bhagavan 27:05

So India had tried to play a role in building partnerships with the Afghan government and to try to play the peacemaker in the region. This is something that India’s neighbor and longstanding rival, Pakistan, did not necessarily look on favorably, because it saw India as sort of leapfrogging Pakistan, literally; meaning jumping over Pakistan to try to forge a partnership with a neighbor on the other side.

Manu Bhagavan 27:40

And so there’s been some strategic competition between India and Pakistan, in Afghanistan over an alliance. And then in the meantime, China has also tried to forge partnerships with Afghanistan. So the US withdrawal in this sense, leaves Afghanistan to be a site of continuing regional gamesmanship between India, Pakistan, and China, as well as the continuing sort of fallout from a very long war, military conflict and bombing campaigns on the part of the West and localized terrorism caused by the Taliban and Al Qaeda. The Taliban is still a force. And people are looking to sort of forge a workable relationship with them in the hopes of creating some kind of peace time function. But how this all plays out is really very much up in the air. What exactly the Taliban are aiming to do, or what they all agree to do, is still unknown.

John Torpey 28:50

Right? So you raise Pakistan, which, in a certain sense, at least indirectly, raises the religious question in India. People forget that India has the world’s largest Muslim population, which I think is in the neighborhood of 300 million people, and of course, this long been not exactly at war with but at odds with Pakistan since the partition.

John Torpey 29:18

And I wonder, modern democracy in India is supposed to be based on a kind of secularism. But that’s obviously been much honored in the breach, shall we say, by the BJP, of which Mr. Modi is the chief figure. And I wonder, what could you tell us about how you expect the religious sort of issue in India, within India primarily, to evolve. What should we expect on that front?

Manu Bhagavan 29:58

Secularism has been on the retreat in India for some time. Originally, when Mr. Modi came to power, he promised development for all and he really made the case that a lot of people’s fears about him were unfounded. People’s fears about him were based on his experience as Chief Minister of the state of Gujarat in the west, where a large scale violence against the Muslim population had occurred back in 2002.

Manu Bhagavan 30:38

Many people had concluded it was a pogrom of a kind; that is, directed violence against the Muslim population. And many people had claimed he was responsible, at least indirectly, or held him responsible or accountable at the very least for those kinds of things. There’s a lot of charges about that. And he and his allies have long maintained that he was unfairly targeted for this, that this is something that had just occurred, and that he wore no actual feelings of this kind.

Manu Bhagavan 31:11

And during his first tenure as prime minister, his first term, he largely hewed to the kinds of claims that he has made. He sort of walked a delicate line between international images, cosmopolitan and a domestic image as a strong man.

Manu Bhagavan 31:32

In the second term, after he won reelection recently, a lot of that veneer has disappeared. And the country has done a lot to start attacking some of the fundamental principles of the founding of the country. And that’s left many minority communities feeling helpless and scared, and at risk. And this has to do with citizenship laws, it has to do with policy for migrants coming in. It has to do with the ways in which various communities are treated in the country. And as we can also see this reflected in violence against various communities as well.

Manu Bhagavan 32:36

So in short, Modi subscribes to a muscular form of Hindu nationalism. He’s never hidden that and he’s never claimed otherwise. But he’s claimed that this Hindu nationalism was something that was not necessarily at odds with India’s original vision that it was meant to erode a false secularism. But in practice, now, we see that that is something which is what people had always feared it was; which is an illiberal philosophy.

Manu Bhagavan 33:16

Now, at the moment in India, Modi’s claim to fame has been as an efficient administrator, and that what he had delivered for the state of Gujarat as Chief Minister was remarkable and unheard of in India’s long history. And that he was going to bring this to the country as a whole. He is a terrific order, and he’s even better at public relations.

Manu Bhagavan 33:50

So people had really believed that he was able to do these things. But what the pandemic is revealing is that the country ultimately has not invested enough in public health, and that its infrastructure cannot bear the brunt of a real crisis. And that in terms of dealing with it, he’s proven right now anyway, to have not planned effectively for India’s defense and that defense against this virus is what is an appropriate way to describe it. And he’s proving inefficient at being able to combat it, to continue with this sort of militaristic metaphor.

Manu Bhagavan 34:29

So I think people are beginning to, well, they’re upset right now, whether this will dent his image ultimately or cost him at the polls or whether it will impact him in any way and thereby impact the overall trend towards de-secularization is yet to be seen, but that’s where we were at a pivot point right now.

John Torpey 34:57

Right, so I want to kind of go back to something you said before, which had to do with the rise and broadening of India’s middle class in the period before the pandemic. I mean, insofar as we can perhaps hopefully see the end, or at least the kind of mitigation of the pandemic. How do you see India coming out of this phase? You said a lot of people had fallen out of the middle class and backward steps were serious. Can it get back on track to being the country that it was before the pandemic?

Manu Bhagavan 35:43

I mean, in the abstract the answer to that is, of course, yes. I mean, one only needs to look at the United States to see how effective policymaking can dramatically change projections, both of the immediate future and, and in the longer term as well. And so, it isn’t impossible that, if carefully considered, and if they place the right kinds of policies in place, that India can get itself back on track, and that it can go back to growing the economy, dealing with inequality in all its forms, and aiming for rapid and large economic growth, while also worrying about bigger crises like climate change, and other things are preparing for that as well.

Manu Bhagavan 36:49

But right now, its immediate concern has to be in mitigating the pandemic and reducing the loss of life and trying to get itself out of a disaster, like a real disaster, a horror show. And, and that exact path forward is unclear, although, we’re beginning to see some advice take shape about some steps that it can take, and hopefully, if the international community gets involved and can deliver certain resources to cut this off, it might be possible.

Manu Bhagavan 37:33

I will say, just on this point, that it is in the international community’s interest and even at national levels. So it’s in the United States specific national interest to stop what is happening in India right now as quickly as possible. And that’s specifically because the more COVID races around communities, the more it transmits, the more variants will generate. And the more at risk everyone around the world will be for, like a variant that is either more transmissible or more deadly or both.

Manu Bhagavan 38:11

And there is right now a variant circulating in India, we don’t know enough about it — B.1.617 — which is often referred to as the “double mutation virus” because it has two particular mutations that make it more transmissible and potentially riskier. We don’t know a lot about this virus, but we do seem to have some evidence to indicate that in some parts of India, it is the variant that is more dominant.

Manu Bhagavan 38:40

And there is this we can use as the example; that the pandemic, left unchecked anywhere, can create very risky alternatives to the extent viruses that put everyone else at risk, including those who are already vaccinated. Right now, it looks like the vaccines can keep everything in check. And everyone, of course, should be vaccinated. But it’s key for all of us to act quickly against any hotspot anywhere in the world, so that we can temper the rapid growth of the virus and its ability to mutate.

John Torpey 39:19

Thank you so much to Manu Bhagavan of Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center for sharing his insights about recent developments in India. Remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Hristo Voynov for his technical assistance and to acknowledge Duncan Mackay for sharing his song “International Horizons” as the theme music for the show.

John Torpey 39:20

Well, nothing could be a better reminder that we really live in one world now. And of course, climate change, the issue of the day in the United States this week, certainly is a similar reminder. But of course, it’s individual countries that have to come together and address these issues. And they don’t always have the same interest or don’t perceive their interest the same way. And, of course, that makes for bottlenecks in addressing these, but that’s all the time we have today.

John Torpey 39:51

This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons. Thanks again, Manu Bhagavan.

Manu Bhagavan 40:28

Thanks for having me.

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

india, people, vaccine, pandemic, country, china, world, kinds, vaccinated, virus, pakistan, united states, population, subsequently, modi, numbers, problem, crises, secularism, terms