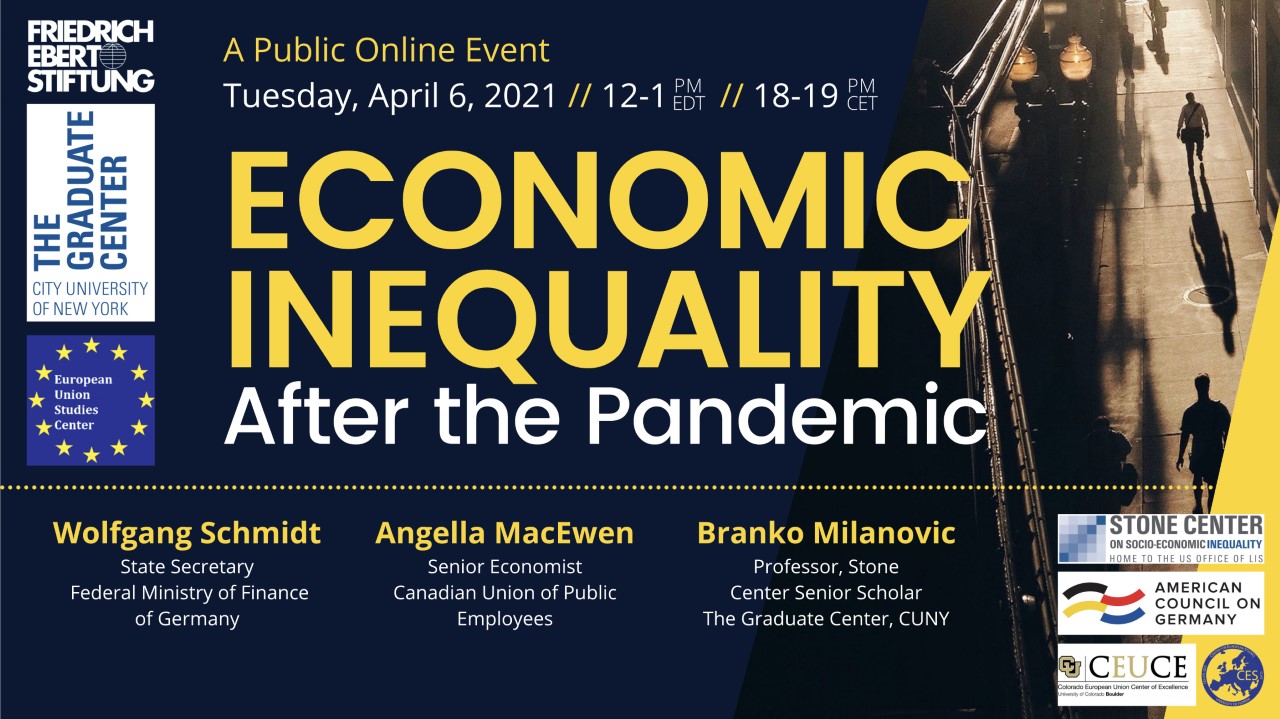

Economic Inequality after the Pandemic

How have governments responded to the economic crisis created by the Covid-19 pandemic, and what will be the consequences? On Tuesday, April 6, a panel discussion with Wolfgang Schmidt, State Secretary, Federal Ministry of Finance of Germany, Angella MacEwen, Senior Economist, Canadian Union of Public Employees, and Branko Milanovic, Professor and Senior Scholar, the Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality, the Graduate Center, CUNY, addressed the inequalities revealed and exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, the public policy tools available to ameliorate those inequalities, and the likely paths economies can take in the recovery from the pandemic.

This public online event was moderated by John Torpey, Director, European Union Studies Center and Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies, and organized with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Washington office. It was co-sponsored by the American Council on Germany, Colorado European Union Center of Excellence, University of Florida Center for European Studies, and Stone Center on Inequality at the Graduate Center, CUNY.

You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud and Youtube below. You can also find a transcript of the interview here or below.

Transcript:

John Torpey

Welcome to international horizons podcast or the Ralph Bunche. Institute for International Studies that bring scholarly and practical expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Today we present a panel discussion on economic inequality after the pandemic, featuring Angela McEwen of the Canadian union of public employees of Wolfgang Schmidt of the German Ministry of Finance, and Bronco milanovich of the Graduate Center. We hope you enjoy the conversation.

John Torpey

Hello, everyone. Welcome to today’s event, a discussion of economic inequality after the pandemic. My name is John Torpey. I’m Director of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies, and of the European Union Studies Center at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Very pleased to be here today and to welcome our three panelists who I’d like to introduce now.

John Torpey

First, we welcome Angella MacEwen, who is Senior Economist at the Canadian Union of Public Employees, better known as CUPE, and a Policy Fellow with the Broadbent Institute. Her research focuses on understanding the Canadian labor market, broader economic trends and the impacts of social policy on workers. She regularly represents the CUPE at parliamentary committees and in the national media. She holds an MA in economics from Dalhousie University and a BA in international development studies from St. Mary’s University. She joins us today from Ottawa.

John Torpey

Next, my colleague Branko Milanović is senior scholar at the Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality at the CUNY Graduate Center. He has served as Lead Economist in the World Bank’s Research Department for almost 20 years. His book, “The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality” from 2011 was selected by the globalist as the 2011 book of the year. Next book “Global inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization” published in 2016, was awarded the Bruno Kreisky prize for the best political book of 2016 and the Hans Matthöfer Prize in 2018 and has been translated into 16 languages. His new book “Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World” was published in September 2019.

John Torpey

And finally, Wolfgang Schmidt is State Secretary in the Federal Ministry of Finance in Germany, responsible for fiscal policy strategy and international economy and finance. He has held a variety of senior positions in the local government of his native city of Hamburg and in German government. Most relevant for our discussion today, Mr. Schmidt served as Director of the Office of Policy Planning in the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. He has a law degree from the University of Hamburg and joins us today from Berlin.

John Torpey

Before we go to the questions, I want to thank our co-sponsors for this event. First of all, the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung or foundation, their Washington, DC, office and Knut Panknin in particular, the American Council on Germany, the Stone Center on Inequality at the Graduate Center of CUNY that I’ve already mentioned, the Colorado European Union Center of Excellence, and the University of Florida Center for European Studies.

John Torpey

I want to thank you all for joining us today, we’re going to have a conversation that will last about 40 minutes or so and then at around 12:45, Eastern Standard Time, we’ll go over to questions. So if you have questions, please send them to the question and answer function.

John Torpey

So, I begin with a question that is obvious for the theme that we’ve chosen, because obviously of huge consequences for many, many millions of people in the countries represented in this discussion and around the world. So the first question basically is, what will be the consequences of the pandemic for inequality within societies? And perhaps I’d like to ask Angela McEwen to begin.

Angella MacEwen

Thank you. So from the Canadian perspective, there were three groups of people that were affected differently by the pandemic broadly. We had workers that could work from home, with their families, and, for them, the pandemic has been stressful, but they’ve largely been able to keep their incomes. And they’ve been spending less money because there’s less things for them to do. They can’t go out to see a movie or, or fly to visit their family or, well, most of them can’t. The very, very rich still manage to do that stuff.

Angella MacEwen

And then there was a group of workers that were laid off. Those tended to be low wage workers in the service industry, and then there was another group of workers that were deemed essential and had to keep going into work. So those are healthcare workers, warehouse workers, agricultural workers. And the pandemic affected each of them very differently. And so I think that the Government of Canada had a pretty good response for the workers that were laid off. They provided immediate financial assistance directly to people. And so a lot of people that were low income workers that were laid off actually got more money from that assistance than they would have if they were working. And so they’ll be financially –most of them– better off after the pandemic.

Angella MacEwen

Workers who had to keep going to work. They had a brief pay bump, but that was taken back by May of last year. And they’re really struggling, because it’s more expensive to go to work. It’s more dangerous to go to work, they have to find childcare for their kids when schools or daycares are closed. And that’s, that’s difficult and expensive. And so it has exacerbated inequality; low wage jobs, without a lot of bargaining power, were least able to protect themselves. And so that’s what we’ve seen in Canada. And I think that’s somewhat what we might see globally; nations that were able to control the virus and lock down very quickly and almost eliminate it, like Australia and some other countries, maybe their economies will perform better than countries that weren’t able to control the virus.

John Torpey

Right. So maybe I’ll ask Wolfgang Schmidt address that question as well, since Branko is in some sense our international sort of roving ambassador.

Wolfgang Schmidt

Yes, sure. And I would say situation is in Germany concerning the labor markets pretty much the same as in Canada. And also, our measures are pretty much the same, with probably one difference to the US and Canada. But in Germany, people were not laid off, but went into short time working. So due to our labor laws, there is more protection, even for low skilled workers, restaurants, and so on, and so on.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And so these people received a bump in their payments, because short term work allowance furlough scheme, only substitutes depending on how long you are in that scheme: 60%, or with children 67% to then 87% of your former wage. But obviously for waitresses, and people working in restaurants, the tips are not compensated. So basically, I would say in labor market, you’ve seen a big problem for those kinds of workers: low skill, low wages. We got a real problem with the self-employed because we realized that our social protection system is not made for these people who never contributed into the insurance system.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And then I would say we have other dimensions of equality that we should also look at. Coming from a man that might sound strange, but I think the gender question is obviously one. So homeschooling I think it [was] made pretty clear that there was in no way a 50/50 share of that workload. So the homeschooling in many families was left with women, with the mothers.

Wolfgang Schmidt

That we also have, I would say, inequality amongst companies. So meanwhile, many of our shops needed to be closed. Amazon and Zoom and, and the cloud service providers, they soared and they saw historic high of revenues and tons of cash. Meanwhile, many others are facing liquidity shortages or even solvency problems. And then, maybe finally, in wealth inequality, I would say, we saw what we saw also before the pandemic, that those who have the stock markets are rising, asset prices went up. So we see this kind of equality or inequality rising as well.

John Torpey

Branko, do you want to talk about this a little bit from a more international perspective?

Branko Milanović

Just a few words. I totally agree with what Angella and Wolfgang said. It is, these are really the developments that we’ve seen. I’m kind of a data person. I still don’t have these developments in numbers. But for example, when I look back to 2007 and ’08, the extension of unemployment benefits under Obama did actually show up in the lower-income households, even in the data.

Branko Milanović

So I would expect this massive amount of transfers and actually the stimulus package also to show up because — and Wolfgang can correct me on that because I may not be right on this — but we have never had in history, such extreme expansion. Were talking about 20% of GDP in some cases. So it will show in the numbers. But of course, there are these other inequalities that both Angella and Wolfgang mentioned, that there may be non measurable in that sense that I’m talking. So there could be inequalities in gender, there could be inequalities in people who actually had lost jobs, and maybe they would not lose so much money, but they really had to basically change to go to work to something totally different.

Branko Milanović

And then there is this really interesting issue of large increases in wealth. And this is not only in rich countries, we see it in China as well, where actually the epidemic was relatively well controlled. But then again, the fact that actually people who are making lots of money, and were working in companies, or owning, right, the companies that do like e-trading, e-commerce, are really doing extremely well. So we have really a very unusual situation very hard to grasp and put in like one or two sentences.

John Torpey

Interesting. The next question I really want to ask is, of course, what do we do about these problems? To some extent, this is basically been a story of the exacerbation of already existing, pre-existing kind of inequalities. And so in that sense, there may be nothing kind of magical or novel that needs to be done. But it is worth saying, of course, Branko mentioned already in the United States that enormous amounts of money are being spent to dig us out of the economic hole that we’ve gotten ourselves in.

John Torpey

But we just hear today that both in New York and yesterday, with regard to the US more generally, there’s a kind of concerted effort going on to raise taxes on the wealthy to collect taxes that are being sort of offshored by American corporations. And try to make sure that this so-called race to the bottom –sort of tax race to the bottom– is stemmed. So what would you say is the best thing or the best things that we can do in response to this, I think, that in terms of the nature of it, not necessarily the size, the nature of this crisis was so unprecedented. Angella?

Angella MacEwen

So I have actually just finished writing a book with a colleague on wealth taxes, and not just net wealth taxes, but the other ways that over the past 20 to 30 years Canada and other countries have cut taxes on the rich, and we’ve deregulated and we made more flexible labor markets. And so there has been a shift of power –steady shift of power– away from the working class, the middle class, towards these multinational corporations. They’re really, really big.

Angella MacEwen

And it’s a global issue. And so I think that we need to start reorienting our public services, our tax policy and our regulation frameworks towards putting people first. Because, the next crisis, or the crisis that was already happening is the climate crisis, we’re gonna need that approach as well. And so we need different thinking about how much wealth is appropriate for individuals to have or families to have.

Angella MacEwen

In Canada, there are over 100 billionaires, while there are people that don’t have anywhere to sleep at night in our biggest city. We’re so wealthy as a country, but we don’t have clean water on in First Nations communities in rural areas. They’ve been on drinking water advisories for years. So I hope that what we see is a shift in priorities and a shift in thinking. A lot of the thinking had been driven by “trickle down economics”. It’s clear now “trickle down economics” doesn’t work. That’s not how you grow an economy. That’s not how you get a prosperous economy. So I think, as an economist, part of the solution is thinking differently about economics and thinking and putting people first in our public policy and in the way we think about economics. And, of course, transfers to people, that’s a start, but that doesn’t fundamentally shift any power relations. So we have to start doing things that will fundamentally shift those power relations.

John Torpey

Wolfgang?

Wolfgang Schmidt

Yeah, again, I pretty much agree. So, on the power question I think it is important. If you look at the sectors that enter workers that are affected — the service industry, the cashiers, the cleaning staff, nurses — very often they are not unionized. And they are not covered by collective wage agreements. And so there’s a problem of power between workers and and the employers. And I think we need to strengthen this idea of collective bargaining. That is one question.

Wolfgang Schmidt

The other one, obviously, is taxation on the on the income side. There, I think, the work that we are doing –and we just got a boost by the US administration on a global minimum taxation and redistribution, so digital taxation, or taxing the digital economy: that we are doing at the OECD. The so-called inclusive framework is important. And hopefully we can finish the works by the end, or by mid 2021 –so this year.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And then there’s the question also how to spend the money. So not to cut in financial assistance. Not to cut social welfare. After the pandemic –and that obviously giving the high amount of debt in many countries– will probably lead us to a new round of discussions, as we saw after the financial crisis. And I think it’s important, especially for progressives, to learn the lesson from the last crisis and not return to a pulse wave of austerity; especially in Europe.

Wolfgang Schmidt

I think that the US, Americans, this time are doing it way better, also, probably was the right amount of money. There’s some dispute as I hear. But for us, I think it is important to continue also to invest into the future, because one group that I forgot to mention when it comes to inequalities, obviously, is children. And children of better off families, they have no problem with homeschooling and dad and mum can probably help even with the complicated math classes. Meanwhile, for families, that even lack the tablet, or a computer to follow digital classes will first need to provide that stuff, and then probably assistance. As they have not seen their teachers for four months, they’re falling behind. And so what we need to do there is that we make sure that there is an equal access to education so that we invest into this sector as well. And I think these are some of the elements that we need for the post pandemic economy and society.

John Torpey

Right. Thank you. So, Branko, from an international perspective, perhaps, how do you see these issues?

Branko Milanović

Let me say something because I cannot avoid saying something from the US perspective first. I’m actually quite, how should we say, encouraged by what are the first moves by the Biden administration, because I think this is really a fairly important change. And given the conditions today with the Congress and all of that, that seems to be the best possible.

Branko Milanović

And when I read, for example, The Wall Street Journal saying that this is like the end of the “Reaganomics”, which basically was reigning supreme from 1980 to today, I feel that there is probably some truth to that. Even if, for example, the corporate tax rate –as we all know– even if it goes back to 28% would be still lower than it was under Obama. But of course, the Wall Street Journal doesn’t really address the level. It says only the change. So it looks only at the delta. But nevertheless, I think it’s an important change.

Branko Milanović

And then I want to point out to another important factor that was kind of seldom mentioned, which indirectly shows the importance of taxation and government. And this is the fact that in this really severe crisis, we really have not had any help from, or almost any help from, philanthropical organizations that every February in Davos, tell us that they’re going to give 99% of their wealth. You know, we have seen this from everybody. They have even websites and they are promising, but if you look at what they have done this time, it’s almost nothing.

Branko Milanović

I know that of course, Bill Gates has done something and I think Jack Ma has done something but from the others I have not heard a word. So that by implication means that if you really have a crisis, all these talks about philanthropical associations, like taking over the slack from the government, they have been really shown empty. And I think we should take this into account in the future and realize that what we really need is need is social coordination. And we need like every organized society, really, to be taxed.

John Torpey

I couldn’t agree more. I recently did some research with a German colleague Hilke Brockmann, and we found that people like McKenzie Bezos gave away $4 billion, but they made more than that in the pandemic because of the shift of all the activity that Wolfgang has mentioned to sellers like Amazon. So, the philanthropic side of this is something you can’t really count on. I think that’s absolutely right.

John Torpey

So, another question, of course, arises about globalization. Many aspects of the crisis have been seen as attributable to the globalization of supply chains, the offshoring of various kinds of manufacturing. How do you see the the pandemic affecting this phenomenon or process of globalization? Angella?

Angella MacEwen

So there certainly has been a discussion in Canada about what types of industries we have chosen to protect and what types of industries maybe we should be looking more at. Like, for example, production of protective equipment. When the pandemic first hit, we didn’t have enough masks, and we couldn’t make them. We didn’t have the stuff that you needed to make tests. We didn’t –we don’t –have a public, really a public research capacity for vaccines.

Angella MacEwen

And we’ve had an agreement with the private sector that they haven’t held up their their bargain to. We have a easy regulatory regime for them. And they’re supposed to then turn around and invest 10% of R&D in Canada –the big pharmaceutical companies– but they haven’t; they’re below 4% now. So Canada has really gone in the 50s and 60s from being a leader in world vaccines on polio and smallpox and other elements of that, to not having any national capacity at all.

Angella MacEwen

And so there is a discussion about should we have publicly owned? Is this infrastructure that we actually need as a country going forward? Do we need to have infrastructure where we’re building our own ventilators here, where we have the parts to make that we need for vaccines. There’s also a concern about the stimulus in the United States, that that will be “buy American”. And so that’s Canada’s biggest trading partner. We’re very integrated from the North American Free Trade Agreement that we’ve had in place since the early 90s.

Angella MacEwen

And so that would hurt Canada, a lot. But before we’ve been able to manage to get exemptions for Canadian production, and to work as a more integrated economy. So we’re hoping that we can do that as well this time. And then if we can do that, the stimulus will help our economy grow. And we’ll be able to ensure that we can share resources with them. So it’s still a little bit up in the air, I think. It’s definitely going to be something especially in the healthcare front, I think that people are looking at a lot more.

John Torpey

Right. Wolfgang?

Wolfgang Schmidt

Surprisingly, again, I share many of what Angella said. And, I mean, we hear a lot about this whole discussion on decoupling. And I would say yes, we see trends toward that, we see export controls, we see something that we don’t like so much; it was in the Biden administration, when it comes to vaccines and a approach of America first. But my general feeling is despite all the trade controversies that we see also with China and other parts, that we won’t see real decoupling and the end of globalization.

Wolfgang Schmidt

Markets and economies are too much interconnected. What I think we will see is obviously a focus on some essential goods and we learned that masks, for example, can be essential goods. But especially on vaccines, we see how important it is to be able to produce them. We also realize that there are global supply chains and we also saw, especially I think, in the first months of the pandemic last year, how vulnerable the supply changes are. And we saw the discussion in Europe, where all of a sudden, we had shortages in the automobile industry in Germany, because parts from Italy couldn’t make it to Germany. Our office called me urgently asking for some parts that were stuck due to the lockdown in near Madrid, in Spain. So we definitely see the flaws and the problems of these global supply chains. But I’m not a fan of the theory that this will end everything.

Wolfgang Schmidt

Nevertheless, I think it will somehow showcase a hierarchy of countries, and, on the top, of this, you have a country like the US that has the dollar and has basically the freedom to do whatever it wants when it comes to export controls, and limiting other countries’ ability to access goods that are produced in the US. And I think that other countries will react on that and will consider I’d say diversification of production. So not to put all your eggs in one basket, but to diversify also regionally, to make sure that you are not the the victim of a sudden change in policies.

John Torpey

Branko?

Branko Milanović

We seem to agree on this one too. Let me let me say actually, for global value chains, in my impression, and of course, Wolfgang and John know that better, but they have survived pretty well. If you remember, in the very beginning, there were some issues in supplies, there were some shortages. But eventually, we actually did really pretty well than the world; much better than we maybe thought in the beginning.

Branko Milanović

It did show some fragilities. And, of course, as Angella said, I believe that many countries will go now into the production of self-sufficiency or certain types of goods. The danger with that? And unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to that, is like all generals, we are fighting the last war. So we will be now doing very well in masks, for example, but maybe the next crisis will be very different. So maybe we’ll need, I don’t know, body protection. So we are little bit fighting this last war, so I don’t have an answer, what would be the next one, but I’m just observing it.

Branko Milanović

And then this next point about global value chain, one thing which might change; and I’ve seen some indications of that, is because of the political relations between the US and China, there could be some… how should I say? Relocation. So globally speaking, the global value chains would remain, but maybe some which would have gone to China might go to Vietnam, for example, or India. So there may be some reallocation. But overall, I think we have done actually pretty well, much better than I think we feared in the beginning.

John Torpey

Great, thank you. So the next question I want to ask has to do with the mobility of labor? How do you think the pandemic has affected the mobility of labor? Obviously, immigration has been a huge issue in the political landscape in the United States in the last five years. And of course, more than that, in Germany, since the arrival of a million or so people from the Middle East and elsewhere, don’t really know so much about the Canadian situation, but it’s obviously been a major kind of issue on the political landscape and is seen, of course, as a kind of inequality and jobs competition issue in many quarters. So how would you expect things to develop on the immigration front? Angella?

Angella MacEwen

So Canada is looking to grow largely by increasing immigration streams. In the past, we focused on economic and high skilled labor for permanent immigration. And over the past 10 to 15 years we’ve increased the amount of migrant workers or temporary workers that we rely on, especially in health care. So in childcare in homes, and personal support workers and also in agriculture. So, workers working in food processing and in southwest Ontario here, where we grow a lot of things like tomatoes. And so, there are a lot of agricultural workers that are don’t have permanent residence.

Angella MacEwen

And so that creates a situation where they don’t have the same protections as other workers. Agricultural workers in Ontario are not allowed to unionize. So they don’t have a union to speak up for them. They access health care through their employer. They live in bunk houses all together. So these workers were incredibly exposed to COVID-19 in the pandemic, and more people became aware of how vulnerable their health situation was, their economic situation was, because if you speak up to your employer, if you acknowledge that you’re sick, and you need to go to the doctor, there’s always the chance that they might send you home because you’re no longer a valuable worker.

Angella MacEwen

And so there are huge disparities in in how migrant workers are treated, how they’re paid, what types of supports they’re able to access, that hopefully, we can address now because more people have become aware of them. There has been a rise in anti Asian hate across Canada with the pandemic. There have been certain premiers, and other political leaders that have adopted Trump’s calling it a “China virus”. And so that has definitely made Canada less welcoming, I think, maybe to some immigrants. And so that won’t be in our favor. As we’re looking to expand our workforce. I think that we’re trying to address those issues. And I really think that that doesn’t necessarily help international equality. If we’re trying to attract the best and brightest to come here, then we’re pulling resources away from other countries.

John Torpey

Wolfgang?

Wolfgang Schmidt

I think it’s still very difficult to predict what will happen, because we are just in the midst of everything. So if you look, I think the OECD, I just looked it up, the OECD international migration outlook said that the OECD countries’ admission for foreigners decreased by 46% in the first half of 2020. We see obviously, short, sharp decline on remittances. We see it –if you look at the refugee numbers.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And I think we have to look at the different sectors of migration. So when we talk about migration, for Europe, for example, we always say we have the free movement of people within Europe as the first group. There we saw after the financial crisis, that intra-European mobility rose because in the south of Europe and many countries, we had economic hardship, so people just made use of their freedom of movement and went up to those countries that were not hit that hard. That might happen again, as we see, many parts of Europe hit very hard by the crisis.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And probably even with all the recovery funds that we now mobilized, we will see some difficulties in Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy, and center and the southern and eastern countries. Then you have the labor migration, both the regular one and the irregular one. There, it really depends on how the crisis and the post pandemic economic recovery develops, both within the countries where there’s the need of labor.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And I think as Angella said, the health care workers is there is in a constant demand. And the same is true for agriculture. And then you might have other parts where there’s not so much pressure. And obviously, the question how the situation evolves in those countries where migrants come from, in Africa for the European case, or Latin America for the US case. Now it depends how hard the economies are hit, how much the pressure is, the push factor, so that people go on the move.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And then you have finally refugees, obviously. This is a question on the international stability. We see things happening Ukraine at the moment with new movements by Russian forces at the border. We in see Syria still a war going on. We see stuff happening in Africa. So I think it’s very difficult to really say what is going on. Then we have –and we’ll come to that, I guess, and Branko wrote about it– the whole question of remote working and teleworking. So what kind of migration will that then trigger or not trigger? Because people can stay actually at home and do their part in their home country and do the same work. So basically, I don’t know. It’s a crystal ball, and it’s blinded at the moment, mine at least, maybe Branko’s is better.

John Torpey

The snow hasn’t settled in the crystal ball yet, but the Branko maybe can…

Branko Milanović

No, I have not actually looked at it over here. But let me look into it later. I think actually, as I said –and Wolfgang said it as well– I don’t want to repeat that, but I do believe that in the longer term, the effect of the crisis would have been really to mimic a global labor market. Simply because many activities we have discovered, we can do it remotely. We knew technically that before, it’s not that the technology was developed now, but we never really did it in such a grand scale that we have now. So I think this will be really a major turning point in that respect.

Branko Milanović

Now, what does it mean for many of these countries? I really don’t know, of course, you will have people staying in that country, and they will spend money in that country. So that’s good for those countries. On the other hand, some people said to me: “well, that would stop the brain drain” but that’s not exactly the case. If I’m actually from Serbia originally, and if I’m working for a Canadian company, and actually have a friend in Serbia who is working for a Canadian company, how does it actually reduce the brain drain? , I mean, has some other effect that he will be spending money in his country, but other than that, there is no reduction in the brain drain. So that’s one issue.

Branko Milanović

Another thing which I think this crisis brought up from the other perspective is what I’ve again seen –I’ve read it about in Hungary, I’ve read it in Serbia, I’ve read it in Bulgaria– shortage of doctors and nurses. Because many of them left because they were much better paid mostly in Germany. So they went there. And then without the crisis, the system somehow managed it. But once the crisis hit, so you really now have a problem in countries that were exporting labor.

Branko Milanović

So we really have a problem not only in countries importing labor for all the reasons that we know and we talked and Angella mentioned, we do have a problem also in the exporting countries, because certain types of professions are not at all easily replaceable. If you need a doctor you need, for example, whatever, seven years of education, so you’re not actually going to produce these doctors tomorrow. So there are many issues that the crisis has really brought to the fore. And, as Wolfgang said before, and I think Angella as well, we are still in the midst of this crisis; we don’t know how it would work out. I mean, if you look at numbers in Brazil, for example, or India, they are actually horrible. And we don’t see yet an ending to this. So really, we are in the middle.

John Torpey

Okay, thank you very much. It’s 12:40, and some questions are starting to roll in. So maybe we’ll turn to the question and answer now. And I want to take a question from my former boss, the interim president of the Graduate Center, James Muyskens, who’s basically asking a question that others are asking as well –which and Branko has in some ways already, you’ve all, sort of spoken to this –but the basic question is, insofar as the pandemic has exposed a number of the pre-existing inequalities, has this created a stronger demand and a collective commitment to addressing those inequalities?

John Torpey

I think part of what Branko was describing is going on in the Biden administration is this kind of notion that we’re in this crisis moment, and Rahm Emanuel famously said: “never let a good crisis go to waste”. And you kind of get the impression that that’s the dominant sort of way of thinking about at least the economic side of things in the Biden White House. So maybe you could speak to this from the point of view of your own, you know, capitals and your own perceptions of the rest of the world. Angella?

Angella MacEwen

Yeah. So in Canada, they’ve done polling and about 70% of Canadians support a wealth tax now and an excess profits tax to help pay for the pandemic recovery. We’re seeing people less concerned about federal government debt than they have been in the past. And we’ve been talking about –CUPE represents a lot of workers in long-term care– and we’ve been talking about the crisis in long-term care probably for 10 years.

Angella MacEwen

But the pandemic really kind of woke people up. And Canada has a mixed public-private system and the private care homes, when there was an outbreak, they had a higher death rate, because they have lower staffing ratios, and because of a whole bunch of other reasons where they’re prioritizing profit over care. And they rely on a part-time workforce, and they rely on a largely migrant workforce.

Angella MacEwen

And, so, I think so. I think in a few areas, parents have also become incredibly aware of how hard teachers work and what that looks like. We are having a conversation around childcare in this country; we’ve been trying to get a universal childcare system in place. I mean, probably longer than I’ve been alive, feminists have been working for this. But it’s a real conversation now. And people are really understanding how it is infrastructure to make the economy work. They’re like, “Oh, if women can’t go to work, then there’s not that production. There’s not that tax revenue. There’s, there’s this, this is missing”. And so this actually, is infrastructure that makes our economy work, just like a road or a bridge would be.

Angella MacEwen

So there are some conversations that are shifting. And I think that people are seeing things –more people are seeing things– that they kind of didn’t have time for before. They didn’t know what’s happening. They were busy in their lives, and they’re like, “I’ll worry about it later”. But it’s kind of made it very difficult to avoid, I think. And I hope that that will spur change.

John Torpey

Right. So Wolfgang. I mean, the Germans are famously debt-averse. How is this impacting, affecting people’s thinking about how to deal with this crisis over there?

Wolfgang Schmidt

Well, look at look at the numbers; we are running a historic high deficit and historic high new debt. So we just added a supplementary budget that is another 60 billion Euro of debt. And so that will amount to 240 billion of debt this year in an overall budget that was planned to have 360 billion. So you see, and people are out in the streets marching and shouting that my boss, the finance minister, should resign.

Wolfgang Schmidt

We will face an interesting time, though, because we have an election in September. And my boss Olaf Scholz is one of the candidates to succeed Angela Merkel who will leave us after 16 years. And so I think we will have, after the immediate impact of the pandemic will hopefully be over in a few months, we will have this conversation, and we will have the possibility for the people to actually speak up by voting and deciding what kind of roads they want the country, the society to take.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And on the international level –because this is the week of the spring meetings that I just came out of one of these informal G7 meetings– it’s interesting to see that both liberal politicians, conservative politicians, progressive politicians, all sing across the same lines. And you can’t really make a distinction between the finance minister of the UK from the Conservative Party, and a Social Democrat from Germany. Or a liberal from France or now (fortunately again) a Democrat from the US.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And so, I think the response to the crisis and the understanding that we need collective action, also on the international level, is there. And that gives me hope. And that is something that I think the world and the G7 and G20 learned from the last catastrophe, the financial crisis, and hopefully learned its lesson for this crisis.

John Torpey

Alright, thanks. Branko?

Branko Milanović

There’s nothing else to say. So, I mean, maybe we can go to the next question.

John Torpey

Right. Okay. Well, I mean, there’s been a number of questions that revolve around the issue of migration. One person is asking whether any of you expect to kind of surge of migration out of places that have not been doing very well handling the pandemic. Of course, many parts of the world, as we know, have virtually no vaccination underway. They don’t have the wealth, they didn’t get in on the contracts. So that’s a big issue; the sort of need for a global vaccination plan.

John Torpey

And I interviewed a couple of Turkish economists not too long ago for our podcast, and they did a study about the economic consequences of not vaccinating everybody. And their main point in many ways was that this is going to be bad for the wealthier countries as well, it’s not just a problem for those countries that aren’t vaccinating their own people. So do you see a successful global vaccination rollout? And how might the failure to do that sort of have consequences for migration. Angella?

Angella MacEwen

So the, it’s interesting that you mentioned that. So there was a request to the World Trade Organization, that they waive some rules in the TRIPS, which is a trade agreement that governs intellectual property. So South Africa and India, asked the council that governs TRIPS if they could waive it for the pandemic, as an emergency.

Angella MacEwen

And Canada and the US –and I’m actually not sure about Germany– have both sort of been dragging their feet saying: “no, you need to justify to us why you can’t do this without us waiving these IP waivers”. And they have, and we’ve still not allowed them to do that. So if most of these vaccines, for example, Moderna’s vaccine, the research behind that was by scientists at the National Institute of Health came up with the innovation, Moderna is publicly funded –a lot of the clinical trials that they did were publicly funded. Even BioNtech and Pfizer got some public funding for their vaccines and they’re using the same innovation that Moderna is.

Angella MacEwen

And so there was a lot of public funding, this is an emergency, and Canada and the US are still dragging their feet and saying: “No, you can’t produce generic versions of the vaccine to make sure that the Global South is vaccinated at least as quickly as we could feasibly make that happen. So you’re going to have to still pay the licensing fees and negotiate individually with them” and kind of work through their own capacity issues.

Angella MacEwen

So that’s a huge issue of inequality that we have baked into our trade agreements that we’re not on doing it an emergency. And we’ve been trying to get –so I’m the Co-chair of the Trade Justice Network in Canada– we’ve been trying to get people to pay attention and to care about this. But people have a lot going on and they’re really, really worried about what’s happening right now. And it doesn’t seem to be capturing the imagination that wealthy countries are ordering all the vaccines for themselves and they’re not allowing other countries to produce generic versions to vaccinate their people. And it will affect us. There’s no question that there will be more contingent variants, that there will be issues with travel, that there will be issues with workforces. And so yeah, that’s a concern.

John Torpey

Wolfgang?

Wolfgang Schmidt

Well, we have been working on that question, obviously, since last year, very hard. And despite this question on the international intellectual property, I think the question at hand at the moment is how to increase the production of vaccines. And that is a big problem. And it seems to be that the modern stuff like the mRNA and vaccines from Moderna and BioNtech-Pfizer are very complicated procedures. And there’s shortages in the supply chain that we are tackling.

Wolfgang Schmidt

But we have the financial means. Germany alone has contributed 2.2 billion Euro to the so-called active accelerator within the COVAX initiative that will provide vaccine therapeutics diagnostics for the world. Other countries are there: the European Union has given this Team Europe, 1 billion; Germany actually is the largest contributor. But the problem remains that there is no vaccines. So AstraZeneca, for example, is producing in India, and they promise –because it’s also Oxford basically that is the research behind it– to provide vaccines at a self-cost basis.

Wolfgang Schmidt

So yes, everybody is aware of the fact that nobody is safe until everybody is safe. The pragmatic problem is –and this is also a political problem, obviously– at least here in Europe, we are having big discussions and in Germany that there is not enough vaccines for the people. So people are really angry and broad support for the government is declining because people are desperately awaiting their shot in the arm. And so any politician saying, “oh, we’re gonna ship millions of doses abroad” will have a difficult time. And if you look at the numbers, actually, Europe is exactly doing that.

Wolfgang Schmidt

Compared to the US, they are not shipping. Europe is exporting millions of doses all over the world, especially BioNtech and AstraZeneca. But on the migration thing –that was the root of the question– I think if you look at migration, it’s basically not the poorest that really migrate to the West. So the poorest normally migrate within the region. Refugees of war, they flee from one African country to the other one. Venezuelans flee to Colombia and to the neighboring countries.

Wolfgang Schmidt

But it’s the middle classes that actually make the move to Europe, or to US, or Canada, with the exception of some refugees fleeing Syria and other parts. And so, it will be an interesting question how the pandemic will [increase] or decrease mobility of these classes –because they do not have the means because of the economic effects of the pandemic– or whether it will push them outside because economic activities do not exist but they still have enough means to migrate. I still think it’s it’s too early again, and my crystal ball is not working.

John Torpey

Right. Okay. Well, Branko maybe has one.

Branko Milanović

On the migration I really don’t know. It is really way too early and we don’t know really how that would affect particularly Africa, which is really crucial for Europe. But on the vaccines, I think this is really a political issue, which will stay with us. Because I totally understand Wolfgang and actually understand fully that countries do display, US especially, this sort of vaccine nationalism. If you look at, for example, US promised like really very small quantities to Canada and to Mexico.

Branko Milanović

And if you want to be really (how should I say) mean, you can actually look on a per-capita basis. So per capita, Canada, small quantity, but per capita got like four times as much as Mexico. So you really see these discriminations very sort of clearly. And on the other hand, you’ll see also the fact which I would not have known had I not read the Chinese paper, that they have actually exported, whether sold or sent for free, one half of their production.

Branko Milanović

Now, obviously, China is in a different situation; they have very few infections, they’ve been put that under control. But people do notice that; they actually received them. So I think this problem would remain. And, as I said, I wrote that on Twitter, I’m a beneficiary of the US vaccine nationalism because I got really vaccinated in January. So it’s very good for me. But we cannot not see it, and actually that will be an issue that will be brought up when it’s over. Like, why did we handle it –when I say we, I mean, the world — handle it in such a way?

John Torpey

Great. Thank you all. We’re kind of running out of time. So I wanted to ask you, if perhaps, you might have a final point or two that you might want to make. We just got about a minute for each of you. Anything you would like to sort of conclude by telling us that you think we shouldn’t fail to know? Angella?

Angella MacEwen

So I think that there is room for positive change out of this. I think that we learned a lesson from the financial crisis, as someone else said. I was living in California at the time and the chant was “the banks got bailed out and we got sold out”. And so governments have made more of an effort in this one to go straight to helping people. I feel like at least in Canada that has been more of the approach.

Angella MacEwen

It’s not entirely successful and we see huge problems in our social and economic structures. We see Amazon making billions of dollars, the owners of Amazon increasing their wealth by billions of dollars, and they’re paying workers in warehouses next to minimum wage. There was an outbreak of 600 people at a warehouse in Canada just recently, and they don’t have paid sick days. So that level of inequality is the kind of thing that makes people really mad. And that pushes them to fight for change. And so I think that we have the pieces in place, that we can really make a difference and make some really important changes in the coming years following the pandemic.

John Torpey

Great. Thank you, Angella. Wolfgang.

Wolfgang Schmidt

Yeah, I share Angella’s optimism. But I think it’s also an open struggle, though; what kind of consequences and lessons we learned from this crisis. And hopefully, they’re economically better than the ones that we learned, especially in Europe, from the last financial crisis.

Wolfgang Schmidt

And then one issue that really concerns me and Branko wrote, or tapped it in an article in Social Europe, that is the whole notion of what kind of an impact will these Zoom conferences and the ability to do work remotely have? And we’ve known that with the programmers and the call centers and so on. But now there is a danger that it hits the middle classes. And meanwhile, we are all happy that we can do that, and so on, companies and employers are looking at it. And I see it in our Ministry; we were building a new office block and now we are reconsidering and thinking, do we really need that much space? And this is the first question, which is good.

Wolfgang Schmidt

But then comes the next question: do we really need to have workers, for example, financial analysts living and working and paying them the adequate wages in New York? Or can’t they do it – and can’t we force them to live in the countryside as well where we pay a third of their salaries? And to think about what will happen, I’m an optimist; I belong to the working group of optimism politics. But this is something that then raises some concerns. And I think we have to be really, really careful that we don’t draw the wrong lessons from this crisis.

John Torpey

Right. Branko?

Branko Milanović

On that point, I would, of course, totally agree. I want to tell you a small joke, which I think now it’s no longer a joke. But when I worked at a World Bank, there was a joke of a guy who comes to be hired as a consultant. And he says, “Look, maybe I cost the same as the other guy who may be better, but I can take a tiny space, so I can live like in a tiny room, and you don’t have to pay the rent for that room. So overall, I will be cheaper”.

Branko Milanović

And it was a joke. But it’s no longer a joke. You know, if I work from home, I’m much cheaper than somebody who is taking a space as Wolfgang was saying, a new building, and you have to pay high rent in New York or Berlin, or Washington or wherever. So I think it is now a reality, that actually, we have to face and it is a new world in that respect for all of us.

John Torpey

Right. Thank you so much. It’s time for us to wind up. I want to thank our panelists, Angella MacEwen from the Canadian Union of Public Employees, Wolfgang Schmidt from the Federal Ministry of Finance in Germany, and Branko Milanović, my colleague from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. I want to thank Merrill Sovner, from the EU Studies Center at the Graduate Center for her assistance in making this event possible and the IT folks behind it all making sure that the trains run on time and that you can see in hear us all. So thank you all for joining us in the audience for your questions, and we look forward to seeing you again soon. Thanks very much.