The Challenge of Climate Change with Michael Oppenheimer, Princeton University

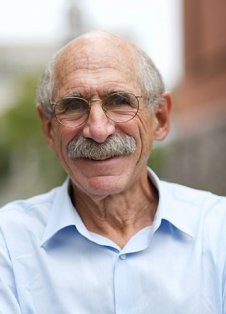

The latest episode of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies’ podcast, International Horizons, is out now. Today on International Horizons we host Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and Director of the Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment at Princeton University, for a discussion on the state of international efforts to respond to global warming and the scientific background to the problem.

You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud below. You can also find a transcript of the here, or read it below.

International Horizons is now up on Apple Podcasts, Soundcloud and Spotify, and you can subscribe to the podcast on whichever platform you prefer. Kindly rate and review the podcast, as doing so will help others to find it.

Transcript:

John Torpey 00:02

Hi, my name is John Torpey. I’m Director of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche institute that brings scholarly expertise to bear on understanding of a wide range of international issues.

John Torpey 00:23

Today, we examine the global effort to address climate change and how the new administration plans to participate in that effort. In order to explore this topic, we’re fortunate to have with us today Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at Princeton University. He’s the Director of the Center for Policy Research on Energy in the Environment, and faculty associate of the Atmospheric and Ocean Sciences program, and the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. Oppenheimer joined the Princeton faculty after more than two decades with the Environmental Defense Fund, where he served as chief scientist and manager of the Climate and Air program. He’s a longtime participant in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. Thank you so much for being with us today, Michael Oppenheimer.

Michael Oppenheimer 01:21

Well, thank you John for inviting me. It’s a pleasure.

John Torpey 01:24

Great to have you. So, let me start with a question about the new administration. One of the first actions taken by President Biden was to reverse Donald Trump’s decision to leave the Paris Climate Accords and to rejoin that effort. Could you describe for us what is involved in the Paris Climate Accords and what they’re designed to achieve?

Michael Oppenheimer 01:46

Sure. First, let me say as someone who’s worked on the climate issue and was involved in the activities that led up to the negotiations that ultimately, decades later, produced the Paris Accords. It’s a very welcome announcement on the new administration’s part. In order to explain the Paris Accords, let me go back in time and tell everybody sort of where they came from.

Michael Oppenheimer 02:13

The climate issue first became an issue of public concern in the late 1980s, when at consensus was beginning to emerge among scientists that this was a serious issue; that it was going to only grow over time and not go away, that ultimately, if the emissions of the gases that were apparently causing climate change, the greenhouse gases, were not controlled, that the situation would eventually get out of hand; human beings would simply not be able to catch up with the rate of climate change. So that it was a problem that required getting ahead of. And that led to a call by scientists going as far back as a mid 1980s for what’s called a framework convention, which is essentially an international treaty, which gets countries on board to cooperating in the reduction of the emissions that cause the problem, primarily, carbon dioxide from the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas and from deforestation, which primarily occurs in the tropics.

Michael Oppenheimer 03:22

The reason why an international agreement is necessary in this case is that no one country, no matter how large are its emissions, could solve the problem alone. US emissions of carbon dioxide used to be the largest in the world. Now they’re China’s, but even China only emits a little more than a quarter of global emissions. And even if you took China’s emissions out of the picture, one would still have a very large, incipient climate change. And things would eventually again get out of control if the other countries didn’t act. So what’s needed in that case is for countries to get together and cooperate and see that no country is what’s called free riding, that is letting all the other countries carry the water for them.

Michael Oppenheimer 04:13

So I could go into some detail about the impacts of climate change but I think we’re all familiar with them now, by having watched episodes like the wildfires in California, which were exacerbated by climate change, like the changes in the intensity of hurricanes, which see more and more category four and five hurricanes strike the US. Again, one of the predictions of the theories that are underlie climate change [is the] changes in extreme heat so that in many areas, though, we get some sharp cold spells sometimes, winter overall isn’t as intense or as long lasting and most places in the Northern Hemisphere and because there’s been a general warming for instance. And summers are getting more and more unbearable and more people worldwide are dying of heat related sickness basically. So this is a problem not only that is predicted to come on, but it has begun already, and is already extorting a large cost to people and to societies in terms of lives and property.

Michael Oppenheimer 05:24

And in the US, one of the biggest impacts is the effect of sea level rise. Sea level rise happens under climate change, because of all the ice melting around Earth and because fluids like ocean water expand when they’re heated. Those effects are conspiring together to eat away parts of the coast and to make flood levels during storms, like hurricanes, considerably higher than they used to be. So that’s the background. So recognizing that this is what was in offing, countries did get together in the early 1990s to negotiate an agreement called the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. UN because it was done under the United Nations. Framework Convention meaning the countries sort of get together to agree on the outlines of what they’ll do in the future, but without specific binding commitments, to say reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide by a certain amount by a certain time. But that framework convention didn’t generate much voluntary action.

Michael Oppenheimer 06:24

So the countries got together again, in 1997, to negotiate a document called the Kyoto Protocol, which had binding commitments for countries like the US, the so-called northern or industrialized countries, to reduce their emissions by certain particular amounts by the period between 2008 and 2012. Again, it was 15 years in the future at that point, so they had plenty of time to do it and to therefore start, but be nowhere near finishing the job of slowing climate change, and eventually stabilizing the climate.

Michael Oppenheimer 07:05

Well, that didn’t work out so well, either. One of the problems with the Kyoto Protocol is that the developing countries like China, whose emissions were starting to be quite substantial, were excluded from obligations under the treaty, those are the developing or sometimes called the Global South countries. Those countries’ economies were expanding much faster than the older economies of the US, Europe, and Japan, for instance. And as a result, there was a feeling in some quarters that there was an imbalance in terms of those countries’ economies getting advantage in producing certain products, which would cause a lot of emissions, while the US, for instance, would be under restraints of not being able to emit so much and therefore the cost of production of some products would become too expensive. And they would ironically get offshored that is ended production would move to China where there was no restriction on emissions. And that was kind of a self-defeating aspect of the Treaty of the Kyoto Protocol called leakage.

Michael Oppenheimer 08:14

That, combined with just an unwillingness in some quarters to recognize the seriousness of the problem, or to pay any cost at all, for restraining it, led the US under President George W. Bush to pull out of the Kyoto Protocol. Kind of ironic, since his father, George H. W Bush, who had a one term presidency had signed the original framework Kyoto convention of which the Kyoto Protocol was a child, you might say. So after that there was a period of disarray among countries, because if the non-binding framework convention didn’t produce much progress, and if the Kyoto Protocol didn’t engage either China by design or the US, partly as a result of China’s non engagement, what else could we do?

Michael Oppenheimer 09:09

And to move forward quickly, there were a lot of meetings and international treaty negotiations, but nothing substantial was agreed on until the Obama presidency meeting or negotiating session in Copenhagen that the President himself attended along with other heads of state. [The meeting] led to a feeling that we just have to rip up much of this and start again. And that in turn led to the negotiation in 2015 of the Paris Agreement, which is a completely different structure than the Kyoto Protocol. In that countries aren’t required to sign on a dotted line for a specific commitment to reduce their emissions, but instead, came to Paris with offers. That is, they say, “this is how much we think we can reasonably do over the next five years in terms of emissions reduction, particularly carbon dioxide, this is how we’ll do it.” And “we will return to tell you what our progress is over the next few years. And you other countries can criticize us.” And that process, called naming and shaming, or pledging or review, is the enforcement mechanism in the Paris Agreement.

Michael Oppenheimer 10:26

So instead of how much is the U.S. going to reduce its emissions being a subject of negotiation between the U.S. and China, say, the U.S. makes an offer. And then if it lives up to that offer, it might get quite a bit of international kudos, particularly if the offer represented a strong effort. If it made either a weak offer or didn’t live up to either a strong or a weak offer, other countries would criticize it heavily. And to some degree, there is traction for that kind of enforcement. It doesn’t work all the time. It doesn’t even work most of the time. But sometimes it works. And it was kind of the only option left for countries, because they weren’t convinced in the end, that they really could reduce emissions at a reasonable cost. So that was one step forward was this agreement to not politically negotiate targets, which would lead countries make their own proposals.

Michael Oppenheimer 11:26

And the second was that China and the other substantial developing countries like India were not excluded this time. They also were required by the Paris Agreement to make offers, to make put down plans and to subject themselves to criticism depending on how they performed. Those are the key elements of the Paris Agreement. And in the meantime, the price of alternative energy, solar energy, wind energy has crashed. There has been such technological progress and such increase in demand, in their economies of scale, so that it is now cheaper to generate energy with wind power, or solar power in many places than it is to burn coal, oil, or even natural gas –the price of which is itself quite cheap– which were the previous ways of, for instance, producing electricity. So we’re in the middle of an energy revolution, which, in the end actually, may be the biggest thing, which makes the Paris Agreement work out. So that’s the basic framework. It’s not perfect. There’s nothing which actually forces a country to do anything, except international social pressure.

John Torpey 12:39

Well, thank you so much for that informative overview of the whole history of this problem and the efforts to try to figure out how to get it wrestled to the ground. What would you say, you sort of speak optmistically about what’s happening in the energy front, and how much of a difference that could make. What difference did it make that the US withdrew from the Paris Accord? And what difference does it make that they’re back in the game? And more generally, what do you see as kind of the greatest difficulties in achieving — maybe you could lay out the specific markers and aims that the Paris Accord sets out — And talk about, you know, what stands in the way?

Michael Oppenheimer 13:27

Okay. I want to say that one specific of the Paris Accord, which I didn’t go into in my first answer, where it’s talking about the next three to five years, for instance, is that there is a long term objective. And this was new, there was a long term objective in the Framework Convention signed, as I said, at the Rio Earth summit in 1992, but it was just the idea of a long term objective. There was no… “Well, how warm could should we let the earth get? What’s the number? One, two, three, four or five degrees above what it was before we started mucking around with the atmosphere, how warm is too warm?” And a lot of science has been done in the meantime. And we now have a pretty good picture of how warm is too warm. And the Paris Agreements actually specify a level which was first talked about in 2009 in the Copenhagen phase of negotiations, but in Paris, it was designated with higher level of specification. In that it’s now an obligation of countries again — not exactly enforceable, but still an obligation — that the ultimate warming be limited to well below two — this is the language of the Paris Agreement — well below two degrees above what it was in pre-industrial times, which is generally taken to be the late 19th century. Although, strictly speaking, they were already some industrial carbon dioxide emission by then. And with a best efforts to reach an even lower warming of about one and a half degrees above pre-industrial levels, I want to put that in context, those are degrees Celsius, you can about double up to get the degrees Fahrenheit, if you’d like.

Michael Oppenheimer 15:21

It’s already more than one degree Celsius now warmer than in pre-industrial times. And that means nearly two degrees Fahrenheit warmer. So that one degree is unfortunately uncomfortably close to that one-and-a-half degree target in the Paris Agreement. And it will be very hard, if I’m still around to see the day, I will be shocked actually, if we actually make a one and a half degree limit. Two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial, where we’ve already not more than a degree, maybe the possibility remains there.

Michael Oppenheimer 16:01

Scientists basically laid out a framework, which indicated that that level of warming above two degrees is pretty clearly dangerous. That is, there’s a concatenation of risk, which increases above around one and a half or two degrees, things happening like destabilization of parts of the Antarctic ice sheet, leading eventually to a very large sea level rise threatening coastal civilization as we know it. Big changes in agriculture, particularly, in the developing countries, but also in countries like the United States, which would deprive some countries of their ability to generate enough food internally that currently have that ability, and in general raise prices of the basic cereal grains making it in some cases difficult for any populations to get adequate nutrition, and other other consequences like more and more of the earth being simply too hot during the warm season for outdoor activity on many days, where outdoor activity just mean kids running around and playing soccer, for instance. And certainly, it would mean workers in the agricultural business or the construction business, we just have a very difficult time and they would be more and more days, where if they weren’t, that’d be taking their life in their own hands. So that’s what the climate danger is. That’s we’re looking at if we don’t keep the warming down below this two degree limit, and that’s the ultimate objective of the Paris Accord.

Michael Oppenheimer 17:36

Now, there are obstacles to getting there, as you as you mentioned. Probably the chief obstacle, as I said originally, is no country is really obliged to do anything. There is no penalty except international disdain. If countries don’t do what they say they’re going to do, or if what they say they going to do. What country x, China says, do what the US says to do, what Japan says, what the EU says… If that doesn’t add up to avoiding two degrees, that means there’s just not enough willpower in the parts of those countries. But there are also some very specific problems with the implementation of the Paris Agreement, which are obstacles to getting where we need to go. Specifically, there’s something called transparency. What that means is that countries have to, in a reliable checkable confirmable way, report their emissions so other countries can see what they’re actually getting done. If we can see what China’s getting done, can we trust them? If the EU can’t see what the US is getting done, how can they trust that we’re actually implementing what we say we are? One day, we’ll be able to see all this from satellites, and it won’t matter will be spying on every country, and we’ll be seeing what their emissions are. But we’re not quite there yet with that ability. So we have to trust the monitoring, verification and reporting of countries that we know aren’t entirely transparent, like China, for instance.

Michael Oppenheimer 19:12

There are provisions in the Paris Accord which need to be specified by further negotiation among the parties, which will have rules for how transparencies are supposed to be carried out, but they’re not there yet. And we know that with the U.S. having stepped out of the Paris Accord for four years and not really paying much attention, the big actor left is China. And there’s no big counterweight to China. And China is, by practice, not in favor of transparency. So one of the first things that’s happened is four years lost of developing rules, which means four years lost globally in terms of really moving toward enough emissions reductions, so we have a chance to meet that Paris goal have two degrees, a one and a half degree limitation on warming. Now, that the US is coming back in, it could provide a counterweight to China’s lack of interest in transparency, and perhaps a reasonable set of rules could be negotiated. That might sound like inside baseball. But if it’s not done properly, the Paris Accord will be worthless.

John Torpey 20:18

Right. So another issue that has beset the discussion about climate change is the question of whether or not there’s a scientific consensus about this problem. And you have serious training in science, if I recall correctly, it’s basically in chemistry. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about what it means to have a scientific consensus on an issue like this? You know, we’re facing it in a more direct way, perhaps right now around the issue of vaccines and whether they’re safe and whether they haven’t been rushed to serve some political end. But, as far as I can see, the usual protocols of double blind clinical trials and all that kind of thing have been observed, as they need to be, and some corners have been cut, but not really, in terms of measuring safety. And that, I think, is the scientific consensus on this issue. But, somebody might say “well, there are doubters” or “I see on the internet, people saying this is not safe.” I wonder if you could talk about what it means to have a scientific consensus, and what is that scientific consensus on climate change?

Michael Oppenheimer 21:40

Sure. Well, there are many mechanisms to get scientists together to tell governments what they think the state of affairs are with respect to many different problems. There’s COVID, with the CDC playing an important role. On climate change, at the international level, it’s the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which has an ongoing process of review and evaluation of the scientific information that’s in the scientific literature, to be able to then state in relatively straightforward language, what scientists understand will be the outcome of emissions at a particular level and why the climate system operates that way.

Michael Oppenheimer 22:24

In the U.S, we have the National Academy of Sciences, which every year produces hundreds of reports on different aspects of a whole variety of problems for the government, ranging from things that are matters of national defense to issues that relate more specifically to scientific research generally and the ability of technology to improve the economy, to a series of environmental problems, including climate change. And so all of these consensuses are operating at once. All these institutions, which do consent — look for scientific consensus, and the process, while it differs from place to place, more or less has certain similarities, namely, in some cases dozens, in some cases hundreds, and some cases thousands, as in the case of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change of experts get together in subgroups. Where we have experts who know a lot about particular aspects of the problem, like how clouds form, and how the warming of the atmosphere will cause changes in cloudiness and precipitation, or why weather patterns get stagnant and therefore, we get persistent heat waves, or why the Antarctic ice sheet is disintegrating contributes to sea level rise. And I’ve been involved in those efforts to reach consensus since the early days of the IPCC, back in 1990. And what happens is that the scientists usually, for free — that is they don’t get paid for this — will spend hours, days, months years, trying to hone down the knowledge in the vast scientific literature, where there are thousands of papers produced every year, with new research findings that need to be incorporated.

Michael Oppenheimer 24:30

Of course, the science on a problem like climate change is evolving very quickly. And so, it’s a it’s a hard job just to read any significant amount of that literature. And the scientists then deliberate over the papers that they’ve read and say “what did you think of this paper?” or “What did you think of this paper?” and they meet — in the old days where there were physical meetings, not that long ago — now it’s done over Zoom or something like that — and they try to reach agreement on some key points. And ultimately, they’re trying to answer questions that the policymakers themselves, who are by and large not scientists, are asking the scientists, because the answers to those questions will be key to making policy. For instance, how much will sea level rise if the Antarctic ice sheet disintegrates by a certain amount over the next 50 or 75 or 100 years? How fast will warming occur? How soon will we get too much drying, so it will be possible to grow certain crops in certain areas because it’s too expensive to irrigate? Those are the kinds of questions the scientists try to deliberate and reach a consensus on. And it has worked, to the extent that scientists have reached a consensus, that is agreement, that certain things about the climate problem are known with a high degree of certainty.

Michael Oppenheimer 25:54

Things like, as carbon dioxide has a very long lifetime in the atmosphere, so that some of the carbon dioxide, maybe more than a third that we emit today, will still be around hundreds and even thousands of years from now, unless we find some artificial way to pull it out of the atmosphere. That means a lot of the climate change we’re building in today is irreversible. Questions like, how much do we have to lower emissions to bring the atmosphere back into balance and to stop the warming? Well, there is a consensus that unless our emissions from fossil fuel combustion and deforestation and other activities that produce carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are essentially eliminated by around mid-century, we will have no chance of getting to one and a half degrees. And unless they’re eliminated by around 2070, we have no chance of getting to two degrees. And there’s always an uncertainty attached to these statements, you wouldn’t say exactly zero at exactly 2050, you’d say zero plus or minus a certain amount, because scientists are always respectful of uncertainty.

Michael Oppenheimer 27:11

And in fact, part of the deal of being a good member of one of these bodies is that you’re willing to say what the uncertainties in any statement you make are, and you’re willing to transmit that to policymakers, because they have to convert what you’re saying into an assessment, not just what they should do, but what the chances are that what they will do and ask the public to do might not work, or will work much better than they thought. That’s what uncertainty is about. So it’s a complicated job, but it turns out that we know a lot about the key features of the climate problem. Just to give you one specific: we now believe that if we did nothing to control carbon dioxide and just let it grow, then sometime late in this century, we would have a warming that would be somewhere between about two degrees and five degrees Celsius warmer than today.

Michael Oppenheimer 28:14

And that warming is unique in the whole history of civilization. And if you even go back to an era where there were large natural climate changes, which occurred more slowly — due to the earth moving in and out of ice ages — you saw warmings going from an ice age to the current type of epoque, which weren’t any bigger than the five degrees. So these are earth shattering changes that would remake the surface of the earth and certainly nowhere in the history of civilization, which is only 10,000 years old, have we ever seen anything like that. And that’s part of the consensus, too, because scientists are a certain subset of scientists, quote, paleoclimatologists, are abled to look at fossil data and similar things and tell us what earth’s old climates used to be. And from that we can figure out how fast did it happen, and this is much faster. Yeah, it’s gonna happen much faster in any global change in the past.

Michael Oppenheimer 29:16

So that’s what consensus is for. It has to be presented in the language of confidence. These are things we’re confident about, these are the things we’re less confident about. These are things that are completely unknown, and we can’t really say what’s going to happen. And one of those, for instance, is how fast will the ice sheets decay. The ice sheets in Greenland that an Arctic and will sea level rise, if you go past the end of the century, into the 22nd century, how much sea level rise we get? Well, there’s just too much unknown about that to have a lot of confidence in it. But we know enough about sea level rise over the next 30 to 40 years, to be able to make sense of the policies, both for reducing emissions and defending the coast at the same time. That latest statement is a judgment policymakers have to make, what the science tells you is, yeah, the uncertainty and sea level rise for 2050 it’s not all that much. And they’ll give a number. So that’s what the consensus process is about. Again, scientists do it for free. And they do it because they think they have a social obligation to try to give policymakers the information they need.

Michael Oppenheimer 30:26

All that being said, you know very well by having lived through the COVID experience, that while policymakers in general are used to dealing with scientists –know how to handle scientific information from the consensus, no matter what the field is, and know how to use that to make judgments about policy, because we pay them to do — the general public has a lighter lesser understanding of the value of the information and is confused when there is sometimes there isn’t a scientific consensus on something. Like in the early days of COVID, there was confusion over whether to wear masks or not, and different scientists were telling us different things, but as we learn more about the pandemic and the nature of the virus and how it’s transmitted, the scientific consensus gelled very quickly, that masks were a key to defending ourselves. Well, that kind of evolution of science is extremely confusing to the public, and in fact, is exploited by people who don’t want anything done about, for instance, the climate problem.

Michael Oppenheimer 31:32

Anytime there’s a disagreement, you’ll see people, many of whom have motivations, not all of them, but some of them have motivations, which aren’t particularly pretty, that is they have a political bias, or they receive some level of support from industries that would be affected by regulation. So some people go about trying to confuse the public on this issue. And unfortunately, a few of those people are also scientists. So being able to tell who’s a real expert and who isn’t, who is giving there and unbiased judgment as best we can be unbiased, and who has a very specific bias that they’re exploiting with the intention of confusing the public. Those are issues with COVID. Those are issues with climate change, too.

John Torpey 32:24

Well, this is indeed precisely where I wanted to go. And I think the parallels are, in fact, quite striking. And the mask case in the COVID example is, of course, exactly on point. And it raises the question, insofar as some people are less familiar with the nature and routines of science, and the fact that uncertainty is always part of a picture to a greater or lesser degree. How do you communicate these? These issues are the findings of scientific research, which are, as you say, never a 100% certain. I think that’s been a major kind of difficulty in our efforts to meet the COVID challenge. And arguably, it’s also been the case with regard to climate change that the communication has been confused. It’s also complicated by social media where everybody’s an expert, it seems. And so I wonder how you would address that question, the question of how the scientific consensus is conveyed or communicated? How it can be made understandable to people who don’t spend their days thinking about uncertainty?

Michael Oppenheimer 33:43

Yeah, that’s a tough question. I spent a lot of my life trying to communicate science. I think it goes without saying that it’s not easy, and certain people have a knack for being able to do well and others or do not. And, in fact, many scientists feel uncomfortable trying to speak about their science in the vernacular. And that all gets to this question of uncertainty, where it becomes how do you express something to people, which you think has a 75-80% chance of happening, but where, you know, the opposite also has some smaller, much smaller chance of happening? How do you get them to understand that? It’s not easy, it’s not easy with climate change, it isn’t easy with COVID, it isn’t easy with anything. But the interesting thing is decision makers and government have to deal with this all the time, and yet they’re able to do it and they’re able to convince people that there’s something there to believe in. And the way it worked, or used to work in a normal world, although there was always some controversy, was that there were people who were trusted in society to essentially translate these messages to the general public in a way, which would bring the public along. And that process worked well historically with some things. It never worked perfectly. And sometimes these so called opinion leaders or intermediaries — called different things, they act in different ways at different times — themselves made mistakes, or were biased and led people in a wrong direction, that can happen.

Michael Oppenheimer 35:27

But in general, when science wasn’t a political football, it was easier for the scientific community itself to develop leaders that would engender trust, and — at least among policymakers and to some degree among the general public — it would be easier to sort of follow the conclusions of what they said the science meant. And then it’s just become harder, because now, if you’re a scientist who espouses the importance of climate change based on certain facts, people tend to ignore the facts and might look first, at whether there’s something suspicious about that, “that doesn’t fit my general worldview, I’m just going to reject it.” Or even that scientists must be “liberal or progressive or a communist.” Yet worse if they believed in climate change, so “I don’t believe their information, because it must be that because they’re progressive,” rather than “they actually have some scientific evidence.” And that’s the way, temporarily I hope, life has turned out. The public is very divided among a whole lot of things, of course, a whole lot of issues. And we see in COVID, this happened with the masks. Or, you might say, where certain people wouldn’t wear masks because they were followers of the then President Donald Trump, and he himself was negative, too “wishy-washy”, on whether masks were a good thing. And therefore, they realigned their beliefs in the science to be consistent with what Trump said. And they decided to disbelieve the part of the science that said we ought be wearing masks.

Michael Oppenheimer 37:19

Same thing on climate change. Some people I want to say, disagree with the science for reasons that might have to do with the fact that they actually took a hard look at it, they know that there are uncertainties, and they have a different view of what ought to be done in the face of those uncertainties. And that’s legitimate. But I don’t think that probably makes up; you know, 2% of the skeptics. Most of them have probably gone about the business of either trying to realign motivated reasoning, realign their belief in science with their pre-existing political beliefs or other cultural dispositions. Or they were just following the wrong people; people who themselves have rejected science for narrow reasons that are either self-interest that is, maybe they own too much stock in oil companies, or maybe the broader political issues, that is, they know that solving this problem will require government action, worse yet international action, and they don’t like the government, they don’t like regulation, and they surely don’t like it getting into agreements with other governments. And those people, you’re not going to convince no matter what, because self-interest is really piled up against them wanting to see anything done with climate change. And they’re not willing to admit it, that it’s a matter of self-interest.

Michael Oppenheimer 38:49

And then there are the vast number of people in the middle who are just trying to figure out who to believe. And here the voices of science, which used to be strong, are drowned out by all this political warfare. So that has happened on COVID; we’ve struggled through it. Not clear that it didn’t already extort a lot of damage; a lot of the 400,000 people in the U.S who died from COVID, probably a lot of them would have been alive if they had been a clear message from the beginning about what the science said and didn’t say. And, as I said at the beginning, some of the science might have been unclear, but very quickly that all got resolved and still, we had the mask war going on.

Michael Oppenheimer 39:36

And same thing on climate change. There were people who would try to fight a rearguard action of the science of climate change. But the good news is that all the surveys with public opinion indicate that the public in general believes that consensus. They believe that earth is warming. They believe that the warming is by and large due to the buildup of greenhouse gases. They understand that unless we reduce the greenhouse gases sharply, warming is simply going to continue to progress and cause damages. And the bottom line is they want to see the problem dealt with. So I don’t want to say that the science wars are behind us. I do want to say that despite this horribly polarized time that we live in, the message from science has gotten through; certain political leaders have provided the necessary leadership, we see a different attitude, of course, on the part of President Biden than on the part of President Trump, and that over time, this is going to lead us in the direction of actually grappling with the problem. The difficulty is, we don’t have a lot of time left to grapple with it firmly enough, so we avoid this warming greater than two degrees.

John Torpey 40:46

It does seem as though things have come to a very difficult pass. So I want to ask you, in conclusion, to say a little bit about what you think is the most important thing that people need to know about climate change that you haven’t said already. And, how could that best be communicated to them?

Michael Oppenheimer 41:08

I think the simplest thing that people have to understand is [that] the problem isn’t going to go away, and it’s not going to go away easily. It’s not like other types of air pollution, where if you shut off all the factories, pollutants like sulfur dioxide would be out of the atmosphere within a few weeks. That isn’t going to happen with carbon dioxide. As I said before, we’re stuck with a certain burden of carbon dioxide, unless progress is made on removing it artificially from the atmosphere. And therefore, we’re stuck with a certain level of abnormal warming for a long, long, long time. It’s irreversible and to that extent, number two, that doesn’t matter whether the carbon dioxide is emitted here, or in France, or in Indonesia, or in China, or Japan, it has the same effect on the climate.

Michael Oppenheimer 42:05

So countries have to pitch in and do this together. They need to also understand that we could make a lot of progress by just implementing technologies we already have. Like I said at the top, the price of solar energy and wind energy has come way down. It’s really economically efficient to start implementing those sources as quickly as possible. And yet, in certain states, there are regulatory barriers, late pick in doing so. Because state government preferring fossil fuels, for some reason has to do with politics. Let’s get rid of those barriers. Let’s strengthen the incentives. Make it quicker for this energy transition to happen to the newer, cleaner sources of energy. Let’s not let money from the industries that are heavily dependent on fossil fuels or produce fossil fuels to continue to filter into politics and obstruct the will of the people on this issue, which as I said, has grown over time into being a broad political consensus that we have to cut these emissions and cut them fast. So at the end of the day, like everything else, these problems are only solved if the political system solves them, the scientists can’t solve them.

Michael Oppenheimer 42:06

But we know enough to act. It’s been a conclusion of most policymakers worldwide for a long time. Let’s clear away those obstacles. Let’s make it easier for politicians to act rather than harder. Let’s let our opinions be heard. For sure, let’s vote on these issues, which started to happen in the last election. And let’s make sure that this problem, the climate problem and solving it, remains a top political priority in this country. At the same time, science is our eyes… we need to keep our eyes open. The only way that’s going to work is if we keep supporting good, solid, basic research in this country. The U.S. has always been the leader in scientific research on this problem. That’s the strong basic knowledge we need to do the sensible thing as this evolves over the coming decades, let’s keep that capacity in place.

John Torpey 44:25

Well, that sounds like the right answer to me. Certainly. Thank you so much to Professor Michael Oppenheimer for sharing his insights about the future of efforts to address climate change and the science behind it. That’s it for today’s episode of International Horizons. I also want to thank Hristo Voynov for his technical assistance. Please subscribe to International Horizons on Apple podcasts, Spotify, or SoundCloud and leave us a review. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us again for the next episode of International Horizons.

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

climate change, countries, scientists, emissions, problem, paris agreement, degrees, science, people, warming, paris accord, scientific consensus, kyoto protocol, carbon dioxide, china, climate, masks, framework convention