China’s Three Child Policy and What It Means for Demographic Change with Wang Feng

What does China’s newly announced three-child policy tell us about China’s changing demographics? What have been the economic and societal consequences of China’s historical efforts to control births? How does this policy fit into a context of global demographic change, and what are the political implications?

Wang Feng, Professor of Sociology at University of California, Irvine, talks to RBI Director John Torpey about global demographic changes across China and the world, and what can we expect in the future from today’s changing global demographic trends.

You can listen to it on iTunes here, on Spotify here, or on Soundcloud below. You can also find a transcript of the interview here or below.

John Torpey 00:04

China has recently announced that it is going to relax its restrictive reproductive policy in favor of trying to promote population growth. What does this mean for China and the world?

John Torpey 00:16

Welcome to International Horizons, a podcast of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies that brings scholarly and diplomatic expertise to bear on our understanding of a wide range of international issues. My name is John Torpey, and I’m Director of the Ralph Bunche Institute at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

John Torpey 00:35

To discuss demography and population policy in China and around the world, we’re very fortunate to have with us today Wang Feng, my old colleague, is Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine, and an adjunct professor of Sociology and Demography at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, one of China’s leading universities. He has done extensive research on global social and demographic change, comparative population and social history and social inequality, all with a focus on China.

John Torpey 01:10

He’s the author of many books and articles and a variety of leading scholarly journals. He served on expert panels for the United Nations and the World Economic Forum. And as a Senior Fellow, and the Director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy. His work and views have appeared in media outlets, including the New York Times, in fact, one op-ed today in today’s New York Times, the Washington Post, the Financial Times, The Guardian, the Economist, and many others. Thank you for taking the time to be with us today Wang Feng.

Wang Feng 01:42

Well, I’m delighted to be here, John, to be interviewed for this topic.

John Torpey 01:50

Well, it’s great to be able to tap someone with your expertise. The main impetus for my asking you to do this is, of course, the recent announcement in the change in population policy in China, and that families are now going to be able to have three children instead of only one. You have published, as I mentioned before, you’ve published just today an op-ed in the New York Times that addresses this policy. Maybe you could just tell our listeners what exactly do you say in that op-ed? And what do you think is the significance of this new policy?

Wang Feng 02:31

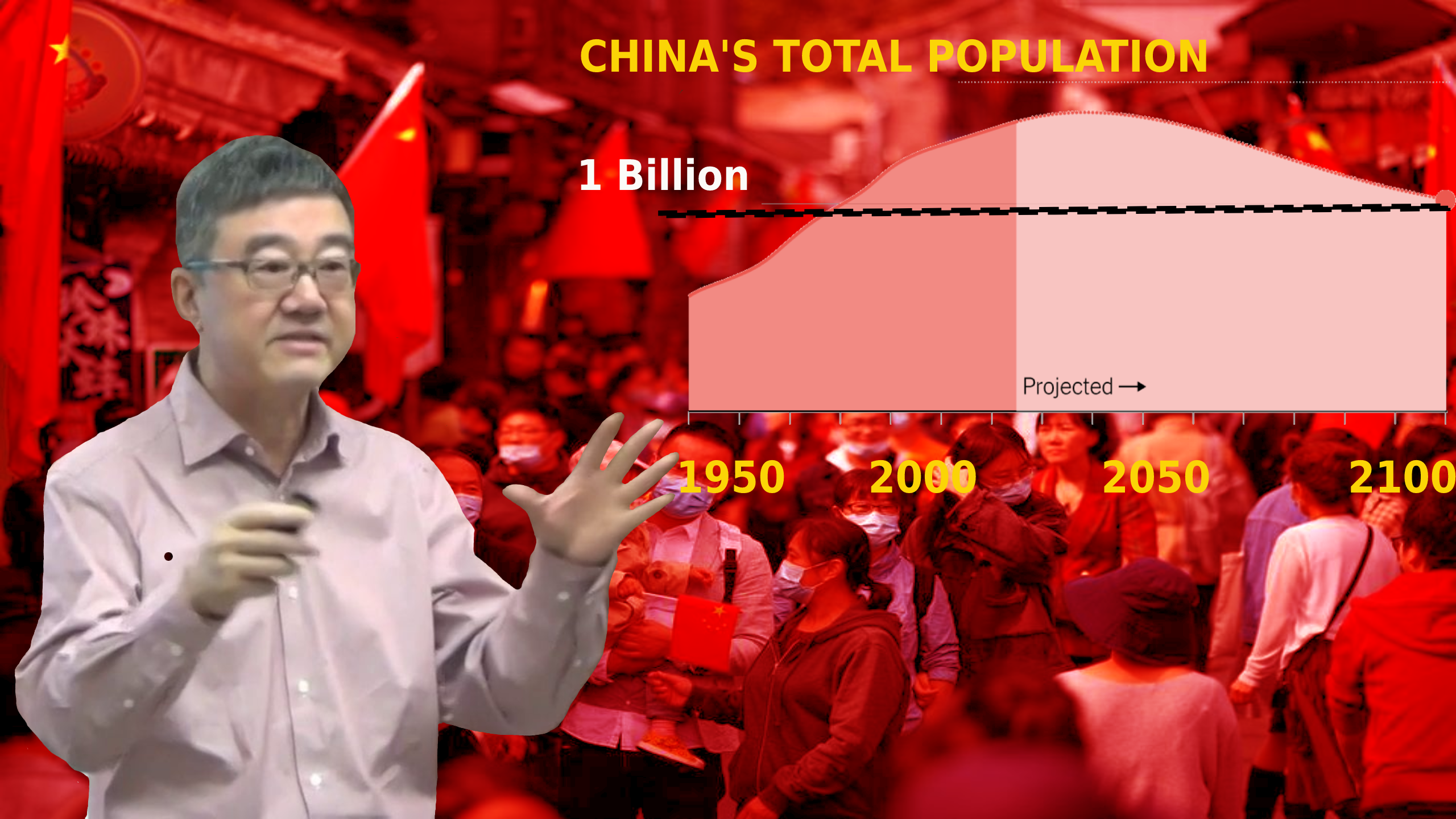

Well, what we’re seeing in China today is in part, really, the global change in demographics in the last half century or so, by the way of a special case, as we’re seeing in China. And I think most people know for 35 years since 1980 until 2015, China implemented the most restrictive birth control policy in the entire world, with a requirement for the majority of the families to have only one child. And so that policy was lifted in 2015, six years earlier.

Wang Feng 03:23

And what has happened, after lifting that extreme policy has been that there is not only no population or baby boom, but a continued downward spiral in fertility level. And the latest Chinese census last year, only confirmed these abysmal demographic numbers. And so the leaders had to do something. And instead of just eliminating birth control policies once and for all –that’s what people would expect– they turned the knob, loosen the knob a little bit by one notch for allowing people to have a three births. So that is the latest move for China. So clearly, I think, China, the leaders, as the public, are fully aware of this seemingly irreversible trend of fertility decline, and soon a population decline.

John Torpey 04:45

But you don’t seem to think in the op-ed that it’s going to actually make very much difference. And I think you were hinting at these broader sort of implications in your earlier remarks about how what we’re seeing in China is really kind of an example of broader changes demographically around the world. And I think I’m intuiting here, but I think what you were implying was that basically what’s going on in China is part of a broader worldwide decline of fertility rates basically, other than in Africa. So maybe you could talk about that broader context that you were hinting at I think before.

Wang Feng 05:24

Absolutely. For you and me, and most people alive today, we’re really living in a what is called a watershed moment in the world history marked by two transitions. One is a unprecedented population explosion, largely in the second half of the 20th century. And now we’re seeing –I think, for a lot of people alive in their lifetime– we’ll actually see the beginning of a population decline. Now, this is not a small deal between the mid-20th century, 1950, and the beginning of this century, in 60 years, the world population tripled from slightly over 2 billion to more than 7 billion.

Wang Feng 06:20

So that has never happened. I mean, that had tremendous impact on everything in this world. And at the late 20th century, the world population was growing at 2% per year. And at that rate, the size of the population doubles in every 35 years or so. So had the world population continued to grow at that rate today, we’re going to see by 2050, the world population would not be seven and a half billion, but it would be 15 billion. Imagine that in 30 years.

Wang Feng 06:59

But luckily, that has not happened. And the growth rate since the late 1960s-70s, started to drop worldwide. And now it’s less than half of the level it was 50 years ago. And by the estimations of the United States, I mean, the United Nations, by all likelihood, the growth rate will drop to zero by the middle of the century, and with a population peaking, probably around 9 billion or slightly over.

Wang Feng 07:40

And half of the world’s population are living in countries where fertility is what is known to be below replacement. So we’re seeing population decline had already started in Japan, Russia, Germany, South Korea, and China within the next five years or so. Being the largest country, in the world, China, and so this is a big deal. So we are seeing the world is turning into population decline in many of the countries.

John Torpey 08:15

It is a remarkable transformation. I mean, not too long ago, a book was written about a term that I think is more widely used, called the Great Acceleration, referring to the processes that you were describing in the mid 20th century, and the massive upsurge of population growth and all the attendant consequences of that massive population growth, including many that had to do with the environmental problems that we now face.

John Torpey 08:46

And so I wonder if you can talk about the factors that led to that Great Acceleration on the one hand, and that are now fueling what we might perhaps call the Great Deceleration –at least on the population side– but will have similar kinds of consequences, presumably, as the Great Acceleration had on the use of resources above all.

Wang Feng 09:11

You know, this is indeed quite interesting. I would say 50 years ago, or 40 years ago, when China implemented the One-Child Policy, the view was that population growth was a burden. But if we look at the last 50 years, the world has had the fastest and the longest sustained economic growth and technological innovation. And measured by per capita –on a per capita basis– standard living increased worldwide. Of course, this is not due to population growth, but it has shown that the growth has not brought the end of the world.

Wang Feng 09:58

So to flip that around, one would say, “well, with the pending population aging and the decline, would we lose that force?” I mean from a very simplistic capitalist point of view, the more people the better because your labor is getting cheaper. Your consumers, this side is increasing. So if you’re producing the same thing, and with no change, so every year, you’re going to be able to sell more. But of course, the reality is much more complex than that. People would need to have jobs, need to have income, need to have education in order to be able to buy your stuff. So it’s, I would say it’s a… the world actually, in a way, has survived the population bomb, but we’re entering into another unknown territory.

John Torpey 11:05

So a lot of this had to do with economic growth, right, and prosperity. And it has to do with the transformation of the world –much of the world anyway in sort of economic terms. And I assume that’s a big part of what’s happening in China.

John Torpey 11:24

And a major reason, aside from female specific reasons, such as the ones you point to in the op-ed regarding with access to education and employment, but these basically all end up being factors that lead to economic independence of women, right. So maybe you could talk about how that fits into the larger global picture.

Wang Feng 11:51

Well, I think what China has experienced, or what has happened in China, this spectacular economic boom in the last 40 years, is an outcome of many historical opportunities. And one of them was this change in population, what we call the demographic dividend. That is during the process of fertility decline, you have, on the one hand, a smaller number of children to support. And at the same time, the population was not aged, so you don’t have many elderly. Then in the population age structure, you have a lot of young people who potentially could be a driver of economic growth.

Wang Feng 12:45

But that requires also institutional opportunities. There’s the context, and China happened to have that; both domestically with its economic reforms, and the globally where the demand, the globalization wave, the demand for cheap goods. And so combined these factors, including the demographic factor, really caused the greatest economic boom we have seen in centuries. So that really changed the face of the world.

Wang Feng 13:22

Now, given that China is the largest population in the world, and given how fast its fertility has declined, and given how many families now have only one child, so China is at a point that it needs to pay back the mortgages in a way the leadership took 40 years ago on the Chinese families.

John Torpey 13:53

Right, so how do you see that going forward in China. I mean, I think a lot of people have been concerned about the factors that you’ve talked about, that is eventually factors that flow in from the One Child policy, eventual decline of population, eventually ageing of the population structure, etc.

John Torpey 14:16

You know, you mentioned that there’s been population decline in Japan, and the aging, of course, the aging phenomenon, where people are wondering who’s going to look after all these old people, because there’s very few young people who could do it. And so, China, as you say, the world’s largest country, or at least it’s close to it with India. And how is China going to address these problems?

Wang Feng 14:47

Well, that is going to be a tremendous challenge, and is a challenge that has been under appreciated, not within China, but I think overseas, a lot of people are sensing “the threat of the rise of China” but in the coming decades, for the leaders in China, for the society, internal challenges are going to be the most important and the most demanding. And everything is going to be driven by what do we see in the demographic change. And well, in the short run, psychologically, I think China is, I hope, it’s getting ready to prepare to be no longer the largest the population in the world. And that will happen within the next five years.

Wang Feng 15:48

So China is going to give that up to India. And it could be national pride, we’re not sure, but the next thing that’s going to be more concerning is the onset of population decline. And that’s very likely to begin also within the next five years. And once it starts, it’s going to accelerate. And it’s going to continue for, at least to the end of the century, because China actually has had a fertility level that’s below the level to replace the population for nearly 30 years. So a momentum is already set in place.

Wang Feng 16:37

And so you’re going to see the proportion of elderly increase to 30%. And that is going to require a lot of resources. We don’t know what’s going to happen to the economy, I think a lot of ways to adapt, the society has ways to adapt. But given the political regime, the system in China, this is going to be particularly challenging, as the government rests its legitimacy on what it could provide to the population.

Wang Feng 17:14

So we’re talking about health care needs. And we’re talking about the pension. And we’re talking about the fertility that’s not going to go up, and people are going to turn around and to blame the government for the high housing cost, for the slowing down in income increase, which is bound to happen, and for the lack of childcare facilities, and you can name it. So all those things would impose tremendous political, not economic necessarily, pressure for the Chinese leadership. So when we look into the future, look at the world, and we’re going to see a China that’s going to be quite different from the last 40 years.

Wang Feng 18:18

We need to remember, China is not only aging, but it has over 100 million household families with only one child. Now, China has not seen, we have not seen the full consequences of the One Child policy, because the parents of the only children generation are still the young old, so in their 60s, so wait until their 80s. And so what’s going to happen to these parents? And when they need emotional support, they need someone to arrange things for them not just to provide economic support, and what’s going to happen to the generation of only children when they have no siblings to even to share their emotions. So China will continue to pay for the cost of this ill conceived policy.

John Torpey 19:25

Right. But it’s not just a policy and I mean, in other words, you started out by mentioning that these kind of phenomena were taking place in in Germany and Japan, in Italy, which as you know, I have a special interest in. And there are lots of reports about houses being given away for free in southern Italy and Sicily because these popular these villages are depopulated, as long as you’ll come and rebuild the structure it’s yours to to have and that sort of thing.

John Torpey 19:56

So I mean, it really does seem to be a kind of global phenomenon. I mean, not everywhere. We should talk about what’s happening in Africa, which still has the world’s highest fertility rates. And the processes that we’re talking about, have not entirely taken hold there. They have taken hold in some places, but not universally. And so, I mean, this process of sort of population decline, you’ve described a very negative set of outcomes, which are certainly predictable.

John Torpey 20:30

But I’m also thinking about what happened in Europe after the Black Death. The fact that, you know, all accounts suggest that wages rose for workers simply because of the decline of their availability, shall we say, I mean, the massive die off that was caused by the bubonic plague. And, shall we call it, the Great Deceleration will have, you know, very negative consequences, let’s say, in the pension realm, or in the realm of, you know, looking after elderly people, but they’ll also have certain positive consequences as well. So I wonder what you would say about that?

Wang Feng 21:11

Well, again, I think as scholars, including especially those who engage in population studies, we got all the basic questions wrong. First, when population was growing, people were so scared to think that was going to be a process that was going to continue forever. That’s why, you know, all these scares of the fertility scares were so prevalent, and that certainly influenced the launch of China’s One Child policy.

Wang Feng 21:54

And so it turns out that the growth was not going to be forever. And it was a temporary process, due to largely not increasing fertility, but the decline in mortality. So that’s why you had so many more people survive. And then very quickly, and with the assistance of government, family planning programs –not the kind of Chinese policy– fertility started to decline. And so the population growth, as we said earlier, has changed direction.

Wang Feng 22:33

And so we got that wrong. And then we got the second question wrong, that was population growth was going to doom the increase in wellbeing, which was not the case. And then the third one that we got wrong was that people were having fewer children because of government restrictions, or birth control programs, like the ones in China. And we know after lifting the One Child policy, even before the lifting of the One Child Policy, that people were adjusting their behavior, regardless of the policy.

Wang Feng 23:12

And so you’re right, historically, we saw what happened after the Black Death, and there was a much study about that, but there are two differences here. One is that we realize that the pandemic, that pandemic lasting a couple of centuries, devastated the whole world. That was, in a way, a interruption, a break in history. And unlike what we’re seeing now, it’s a continued trend. It’s not something that you can rebound quickly, at least from what we know, to raise fertility.

Wang Feng 23:59

And the second, also, remember young. Even that I won’t say conjecture, but even that historical effect, the ones you talked about, it actually took decades, or even longer than decades. So I think for someone who’s studying history, you look back as, “Oh, that’s only a small segment of history.” But in terms of human lives, that is one or multiple human lifespans.

Wang Feng 24:36

So whether the people who are living now or next generation would feel the same way about this shift, there’s the population decline. But I don’t want to be pessimistic because just like the world adapted through this extremely rapid population growth, the world just got so crowded within 50 years. And, I trust, human beings would have a way to adapt a world that’s getting older and older, and populations getting smarter, smarter. So we could envision a life where you just walk out the street, two out of every five people are in their 70s, 80s, or even older, and some of them are still look very athletic, very young, very strong, like you right now. And then you have much fewer people who would be in schools, who would be working, but it doesn’t mean that the standard of living would necessarily be lower. And the world is already producing more than enough for everybody. So it’s really a distribution issue. Right? So we don’t know what’s going to happen 50 years or 100 years from now, and but we do know, I think there are ways that people can adapt.

John Torpey 24:58

The redistribution issue is a really interesting one. I mean, I think that part of the reason that you’ve heard comments about, negative comments from young people about Boomers, is that they have a lot of the resources. And you know, younger people, certainly in places like France, and it’s partially a product of their laws, but younger people in France, let’s say, have a harder time getting a footing in the employment system. And I think this anti-Boomer sort of animus is part of this.

John Torpey 26:56

I mean, I’d be interested to hear you say a little bit more about how you see this redistribution or distribution question in a world that consists much more proportionately, much more of older people who presumably have, you know, exited the employment system and are living off of whatever kinds of accumulated assets, whether public or private, there may be. I mean, you are in California. You know that the California pension system faces major challenges. And that’s true in lots and lots of places. So, they just cannot meet their pension obligations. And how do you see that working out?

Wang Feng 27:38

Well, this is, again, one of the other great ironies of history. And the large cohorts born in the West after the World War Two, the Baby Boomers, one would think that because of larger sides, they would have a harder time to find new jobs, and they would have a lower standard of living. But to the contrary, they rode the wave of the greatest economic boom, the Second World War, the post-war, economic boom. And as a generation, they are a wealthy generation. There is a lot of study data showing how young people now, compared with their parents, how much worse off they are at the same life stage.

Wang Feng 28:37

And then you look at other countries: Japan, South Korea, China. Again, it’s the same thing. It’s this one generation, like my generation, benefited, or my parents generation in China, they benefited from this post-war, much later economic boom. Specifically, it is a property boom, that is when the land the how or the real estate started from worth nothing to exorbitant prices. So these people have a lot of wealth in their hands.

Wang Feng 29:14

So perhaps, if we go back to the Black Death, that is, but you can use pandemic, not like COVID 19, we can say this is the design of God. So when these older people die off, and some of the wealth would be transferred to or be used by the next generation. But as you know, distribution is not only intergenerational, it’s also more important is intragenerational. So I think policies would be quite important to think about this intergenerational inequality, that is the wealthier boomers are able to pass down their wealth to their children, while others will not be able to have this. So I think in the next 30 years or so the world actually faces a major intergenerational and intragenerational wealth and income redistribution challenge. And, there have been so much studies on inequality a couple years ago. This was on that headline. I think it’s going to come back again, the world again does not lack enough resources. It’s just we have such an unequal distribution.

John Torpey 30:50

Right. I mean, I hadn’t planned to ask really a question like this, but you know, much of what you say, really reflects, in a way, the fact that we maybe don’t spend enough time paying attention to these demographic sorts of questions and issues. And, you know, an op-ed, such as yours in the New York Times today is a relatively rare event, and, obviously has something to do with the perception of China as a challenger to the United States for global hegemony and that sort of thing.

John Torpey 31:24

But your piece sort of makes, among other points, one of the points that seems to me to make is that demographic outcomes are the product both of policies and of private personal decision-making that in a certain sense is beyond the reach of policymaking. But those are things that we need to understand in order to understand the dynamics of demographic change.

John Torpey 31:51

And I was only, unlike you, I was only smart enough to figure out that demography was important well into my career, really. I was writing a book, as you know, about the history of passports and I had a kind of late in life mentor and very wise guy named (not wise guy), but a very wise scholar named Aristide Zolberg, who impressed upon me the importance of understanding the dynamics of demography. So is that something we spend enough time paying attention to? Do we train enough people who were paying attention to these kinds of questions?

Wang Feng 32:27

I wish the discipline could be wider, could be more interdisciplinary, they are more scholars like yourself. You know, your passport book was 30 years ago. That’s way ahead at the time of –look at immigration. Again, the world as a whole, it’s slowing down into population growth and it’s approaching in the next 30 years to zero population growth and then starting decline. But in terms of different regions, it’s unbalanced, that you’re going to have pretty serious decline in certain parts of the world and then you have continued growth in other parts. For instance, in Africa, you have a need for labor, and for people. And then you have other countries, they have the need to… well, young people want to get out to find jobs. But that creates what I think the world has been already seeing in the last couple of decades after you wrote the book on passports. And it’s the political issues associated with immigration, right?

Wang Feng 33:54

So the demographic imbalances are driving these immigration waves in different countries. But then you have the rise of anti-immigration and extreme-right, and you name it, right? It’s all associated with this xenophobic mentality. So indeed, I think when we look down the road, what we’re seeing today in China is only a part of a global trend. And what we’re seeing globally is –with this uneven unbalanced demographic change– is going to be a world where no longer the concern is on the growth of population in some developing countries. Like several decades ago, the growth of China people are very concerned about growth in China, in Asia, but it’s going to be the concern of this new, unbalanced demographic landscape, and how that’s going to change the world.

John Torpey 35:16

Right? So, you’ve mentioned Africa a couple of times. So I want to ask you, I know it’s not necessarily at the center of your research, but I’m sure you know, a lot more about it than most of us. So, you know, I can remember reading a book by Paul Kennedy, 20 years ago –I’m not sure maybe it’s 30 years ago now –called “The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers” (I’ve forgotten the title exactly).

Wang Feng 35:41

It’s exactly right.

John Torpey 35:43

And he talks about Africa in a chapter, in which he refers to it as the Third World’s third world, which is to say, this is a place that’s really beset by poverty, and probably other problems. That’s not true of Africa really anymore. I mean, it’s true of parts of Africa, of course, but they’re have been major improvements in the wellbeing of many of these societies. And, you know, improvements in life expectancy, in economic, in wages and wealth, and in sort of the ways in which people there get sick and die. That is, it used to be primarily contagious diseases of the kind we’re facing now, and has now increasingly become the chronic diseases that also kill people like us in wealthier societies. So it’s not the Africa that Paul Kennedy was talking about, it seems to me, and yet, it still has the highest fertility rates in the world. I mean, as a continent, which, you know, I hasten to add is very diverse and complicated. So I wonder, you know, how you would sort of describe the Africa that’s come into being that I’ve just tried briefly to describe, and in what ways it’s changed since Paul Kennedy wrote that book.

Wang Feng 37:04

There are tremendous changes. We have to understand, I think, now, international donors, and also organizations now have a better understanding of population growth. That is, you can’t just go after how many children people, how many births people have. You first have to deal with survival, with infant, child and maternal health. And just like what we’ve seen China and elsewhere, fertility was high in the past, because infant and child survival was very low; you’re talking about infant mortality of 250 per 1000, that’s 25% of births die within the first year. Now, that was the case 30 years ago, and in the majority of countries in Africa now, infant child mortality has dropped to below 10% or to 15%.

Wang Feng 38:14

And that’s very important, because if we know what happened elsewhere, is that when once you improve the health of infant and child and the mothers, and that’s when people will start to rearrange their lives to have fewer births. So in many countries, like in South Africa, and north African countries, fertility dropped to below three now. So it’s just a matter of time. And I think within the next 20-30 years, we’re going to see an entire different Africa, there will still be countries that will be very poor, health level will be very low, but in the last 30 years, health, especially maternal and infant and child health has improved tremendously. So that is setting a stage for fertility decline in those countries, if what we’ve seen in the rest of the world so far bears out. So we shouldn’t be just simplistically negative or pessimistic about the continent of Africa, a lot has changed. And we are seeing a new beginning there as well, thanks to this great global effort to provide support to improve health.

John Torpey 39:45

Right, indeed, I think that’s been an important source of improvement, of course. The Sustainable Development Goals of the UN I think also have been a major kind of sources of incentives for some of these achievements and the shift from the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals, because world poverty was reduced more quickly than anybody really expected that to happen. I mean, all those are very good things. But I suppose one thing one might add to that is that the pandemic, our pandemic, has short circuited some of those developments and undermined them in various parts of the world.

John Torpey 40:27

And so as we wrap up, I think maybe the last question I’d like to ask you is about the pandemic and its effects, as you see it on the United States, perhaps, and around the world. You know, there had been as my colleague, Branko Milanovic, has pointed out in some of his books, there has been this kind of relative equalization of wellbeing and wealth across countries, not so much within them, of course, but across countries. And the pandemic seems likely to upset, I think, some of those trends. And I wonder how you see the pandemic affecting global demography.

John Torpey 41:13

I mean, it seems like it will have very limited very small, if any effects really on China, given the size of the population, and what I know to be the death rates and that sort of thing. Whereas in the United States, it’s a very different story, but it’s still not the story of let’s say, 1918, where population was a quarter of the size it is now and deaths were more than their official, at the official count that we have the United States today of around 600,000, it was even higher in 1918. So I wonder how you would you know, sort of contextualize the effects of the pandemic on global population and wellbeing, as we seem to exit it, you know, here in the United States, but not so much in India or Africa.

Wang Feng 42:06

You know, as someone who studies demography, the pandemic is a major interest of the demographic process. And the world has gotten to be so large in terms of population. First and foremost, was the receeding of these pandemics in the past. So the last one we had was a century ago. But given what do we know now and given the changes in the world, viruses do not have a time clock. It’s not to say these kinds of viruses would come back in 100 years; we don’t know when the next one’s going to come.

Wang Feng 42:55

So demographically, I think we are in a way lucky, so far, that, as you said, the death toll is not as high as the last global influenza 100 years ago. And I think we lucked out in many ways. In the United States, most recently, it’s because of science, right? The MRI vaccine, this is something that never happened before and we’re really lucky. In the previous viruses, it will take years or decades to get a vaccine out, but this time is fast. But we’re not finished yet. And for a while, we thought India was safe. And then look what just happened to India. We don’t really know what will happen to Africa.

Wang Feng 43:53

And so I don’t think the story is over. So we’re still waiting, hopefully, to see that Africa would not become the next India. That’s large continent, and with a very primitive poor infrastructure for health and for immunization. And I think what we’ve learned so far is less about pandemics, about technology, but more about, again, getting back to this topic that’s dear to our hearts; about politics and inequality.

Wang Feng 44:40

And so, we are not putting on a period for this unusually long segment of history that has been more than a year, living under this pandemic. And also as you know, that death rate could be much higher. Look at what happened last year in the United States, look at what just happened to India. So there are a lot of measures that allowed us to suppress the severity of the pandemic. But what we’ve seen is, again, the same themes of inequality and the political stability, both in this country and the other countries as well.

Wang Feng 45:32

Look at Brazil, look at India, look at the China. China relied on the method that was used the five centuries ago, which is by quarantine, by isolation, through its political organizations. But then now, it’s because of the overconfidence in the administrative measure. This is a primitive measure; doesn’t meet with the model efficiency. China has been very slow until very recently in vaccination. And there’s no reason, I don’t understand why, the vaccines developed by the firms outside of China could not be used to produce vaccines for the whole world including for people in China. But the Chinese would, for political reasons, say, “we want to be self-sufficient, we want to show the advantage of our system, so our vaccine is more effective than any others and we can export it to all over the world.” So again, we are victims of our political systems. That’s not a very happy ending for this. But unfortunately, I think that’s the reality we live in.

John Torpey 47:01

Well, I’m sure that’s right. And obviously it gives us an incentive to have better political systems. So hopefully that will be in our future. But I want to say thanks for today’s episode, I want to thank Wang Feng for sharing his insights about world demographic developments, especially those in China.

John Torpey 47:20

Remember to subscribe and rate International Horizons on SoundCloud, Spotify and Apple podcasts. I want to thank Hristo Voynov for his technical assistance and to acknowledge Duncan MacKay for sharing his song International Horizons as the theme music for the show. This is John Torpey, saying thanks for joining us and we look forward to having you with us for the next episode of International Horizons.